An Evening With The Godfather

Flashing back to the only time I ever saw James Brown in person

(Mural in Augusta, Georgia, taken October 2020 by me.)

Before we get on the good foot and let a man come in to do the popcorn, I have some exciting news to share: Jagged Time Lapse has now passed the 500 subscribers mark! That’s a pretty gratifying milestone, especially considering that this Substack was initially conceived late last summer during a COVID fever dream as a way to keep myself sane and focused during a period when everything in my life was falling apart. I can’t thank you enough for your support, especially all you “paid” folks out there. It is such a joy to have a built-in audience to write for…

For whatever reason, I’ve been seeing a lot of James Brown-related posts from Facebook friends over the last few days — maybe just because I have a lot of friends with good taste — and when The Godfather of Soul came up in conversation with another pal yesterday, I took it as a sign to pull this favorite tale out of my funky bag…

Back in the summer of 1991, word went around Chicago that there was going to be a massive soul music concert at Soldier Field, the 55,000-capacity home of “da Bears”. Aretha Franklin, Al Green, Johnny Taylor, Little Richard and several other legendary acts were all on the bill, with a just-out-of-prison James Brown as the featured headliner. In other words, a not-to-be missed event. My bandmate Bob and I bought tickets in advance — and when the big day came we twisted up a few joints and caught the bus downtown with a few of our friends, looking forward to an afternoon and evening of pure soul satisfaction.

It felt appropriate to be going to see JB with Bob, as no one had been more instrumental in helping me understand the importance and innovative brilliance of The Godfather’s music. I had been a fan of classic ‘60s soul music for years, but my tastes had generally run hard towards the Otis Redding/Wilson Pickett side of things; I liked soul songs with indelible melodies and choruses, and soul singers who could wring every last deep drop of emotion out of them. James Brown’s sweaty, skeletal funk bursts were much harder for me to wrap my head and ears around; even the funkier ‘70s stuff I’d grown up on and loved, like Parliament and Chic, sounded more song-oriented, more musically fleshed-out to me than what James was laying down. While I dug his ballads like “Try Me” and “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World,” I honestly didn’t “get” the harder, more stripped-down JB numbers like “Cold Sweat,” “Super Bad” or “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”.

The late-’80s were a tough time for James, a period marked by steeply declining commercial fortunes and brushes with the law, most infamously the PCP-laced 1988 interstate police chase that landed him in prison on various gun- and drug-related charges. James Brown had become a national punchline by this point, but Bob saw no humor at all in his predicament. “James Brown is a genius,” he’d say. “All these people who are laughing at him right now have no idea.”

Not that Bob didn’t find plenty to chuckle about in James’s free-associative 1986 autobiography, or in his often self-aggrandizing way with a lyric — but he also had nothing but respect for The Godfather as an artist. When we moved in to the Lava Sutra house together in the summer of 1989, he spent countless hours spinning JB LPs and CDs, schooling me in both the man’s rhythmic brilliance and the stories of his herculean work ethic, as well as pointing out all the beats that had already been sampled by hip-hop artists. The In The Jungle Groove collection was a big one for him, as so many of its tracks really seemed to distill James’ music down to its funky essence.

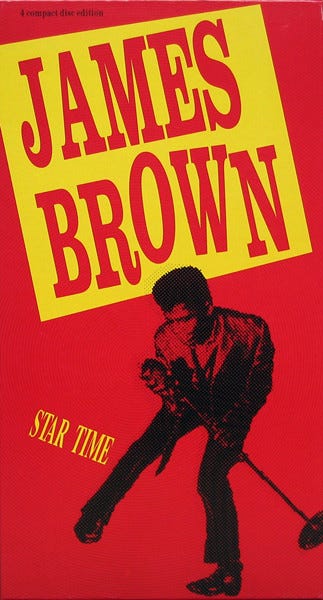

By the spring of 1991, when the career-spanning four-CD box set Star Time was released, I’d become a fervent JB convert thanks to Bob’s efforts, with the fantastically funky 1969-72 period as my particular “sweet spot” — though I also deeply loved such mid/late-’60s groovers as “Bring It Up” (probably my all-time favorite James Brown single) and “Get It Together”. We knew that he’d lost a step or two in the ‘80s, even if “Living in America” had been a fluke hit, but we were still totally stoked to see the man in action at Soldier Field. And with so many other soul greats in attendance, how could we lose?

Unfortunately, the reality of the concert turned out to be far more mundane and frustrating than advertised. The event had also been poorly promoted — the Chicago Tribune reported that there were only about 10,000 fans on hand for the show — and word quickly spread through the crowd that some of the acts on the bill were refusing to play unless the promoters coughed up the cash before they went onstage. (That is, if they had even shown up; while Aretha was briefly spotted on the sidelines, it was later revealed by the Chicago Reader that many of the advertised acts had never even agreed to appear in the first place.)

So that left us with a handful of acts, and a whole lot of space between them. Up first was a local singer named Artie "Blues Boy" White; he was decent in a Bobby "Blue" Bland kinda way, but his act got boring pretty quickly. It was even more boring the second time around — the next scheduled act (I think it was supposed to be The Dells?) had failed to appear, so the promoter made him run through his entire setlist again. “Oh honey, I sure am sick of this one,” dryly announced one of the several older Black women seated in front of us. These ladies perked up a bit when the new Luther Vandross CD was aired out over the PA system following White’s set, and then even more so when the sorely underrated Gene Chandler took the stage to deliver such classic Chicago soul hits as “Rainbow ‘65,” :Just Be True” and his doo-wop chestnut “Duke of Earl” (for which he busted out a top hat, cape and cane). It was a killer set, and to this day I’m grateful that I got to see the man in action.

After an interminable wait, The Chi-Lites (featuring maybe one original member?) finally took the stage and ran through a number of their top hits like “Oh Girl,” “Have You Seen Her,” “(For God's Sake) Give More Power to the People,” — but then, like so many R&B acts I've seen before and since, they ignored some of their best songs in favor of a completely unnecessary Motown hits medley. They left the stage, and the new Luther Vandross record came on again… and continued to play over and over again for the next two hours while we waited for someone (anyone!) else to take the stage. “Oh honey, I sure am sick of Luther,” the woman in front of me said with a weary shake of her head.

Other than the absent artists and the sourly pervasive sense of rip-off that began to hover over the stadium, the thing that sucked the most about the show was the seating. This was late July, so the NFL pre-season was right around the corner, and the Bears didn't want to take a chance on having their field ruined; therefore, all the fans had to sit up in the stands. Since the stage was set up in one end zone facing the other, you had to crane your neck hard to the right (or left, if you were seated on the other side of the field) to watch the performances. The sound (and sense of connection with the performers) would have probably been pretty decent if we'd been allowed to sit or stand on the field; instead, the sound was shitty, and I felt oddly disconnected from the whole thing, like I was watching the show via a security monitor. Of course, the fact that we'd smoked several joints by now (more out of boredom than anything else) probably didn't help…

Finally, after what seemed like days, Al Sharpton (who was still rather large back then) waddled out onto the stage. He attempted to rouse the sullen crowd with a sermon about how “We did it” — who the “We” and what the “it” was, wasn't really clear — but got a loud cascade of boos in return. After sitting there for eight hours, people were bored, angry, hungry (there were no concessions open at the stadium) and feeling ripped off; funky music, not words of inspiration, was what they wanted, and they wanted it now. I remember thinking that if James Brown didn't show up soon, there might be some real trouble.

But moments later, James Brown finally hit the stage, and all the anger and negativity instantly vanished into the ether. I couldn’t tell who was in his backing band from where we were sitting — the Tribune’s write-up of the night would mention saxophonist Joe Poff, drummers Tony Cook and Arthur Dixon, and, er, “saxophonist Clair St. Pickney” as opposed to St. Clair Pickney, his actual name — but they were extremely funky and ridiculously tight, just the same. (He also had a very Vegas-y troupe of showgirls who came out every few songs to shake their stuff, but were completely surplus to requirements.)

With the exception of "Living In America," everything in the set list came straight from the ‘60s and ‘70s — “Sex Machine,” “Get Up Offa That Thing,” “Try Me” and “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” were among the highlights of the show. James' voice was a little hoarse, and occasionally threatened to give out, but the man's energy was absolutely unbelievable. After his time in prison, he could probably have just phoned in the set and gotten away with it, but the man was clearly on a mission — a mission to kick some serious ass. And since there was no room for dancing in the seating areas of Soldier Field, James had clearly decided that he was gonna dance for all of us.

The most memorable (and beautiful, and surreal) part came at the end of the show, when James apparently decided that he needed to be closer to his adoring fans. As the band vamped up a storm behind him, he sat down on the edge of the stage, which was a good ten feet above the playing field. He gingerly scooted himself off the edge, and dropped to the field, landing awkwardly on his right foot. He staggered for a second, as if he'd sprained his ankle, but then took off running, zig-zagging his way across the field in order to commune with the audience in the stands. At one point, he ran directly towards our seats with an insane smile on his face, looking like a cross between a joyful preacher and the sort of evil gnome that chases after you through your nightmares. His arms stretched wide as if he wanted to embrace our entire section — and God knows, we all sure wanted to embrace him back.

The moment was so surreal that I wasn’t even sure it had actually happened. We were all too stoned and tired to talk much on the way home about what we’d seen; but over breakfast the next day, I asked Bob, “So… was James really zig-zagging back and forth across the field at the end? Or did I hallucinate that?”

“Oh yeah,” Bob smiled. “The Godfather moves in mysterious ways!”

Those dance lessons were nothing short of brilliant. Each executed perfectly and none crossing over to another. I thought of classical ballet “positions” and Balanchine.

All the fault of "Chicago's biggest small-timer" Pervis Spann:

https://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/not-so-smooth-operator/

(search for the word "nadir" to get to the Soldier Field fiasco).