And After All This, Won't You Give Me A Smile?

A timely reconnection with The Clash's London Calling

Long Island’s Jones Beach might not seem like the most obvious spot for a punk-rock epiphany, but that’s exactly where mine occurred in July 1980.

I was stretched out on a beach blanket — nose buried deep in my copy of Bulfinch’s Mythology, and stubbornly resisting the entreaties of my family to join them in the waves — when I heard choppy guitar chords ringing out from a nearby transistor radio, along with the clarion cry of “London Calling!”

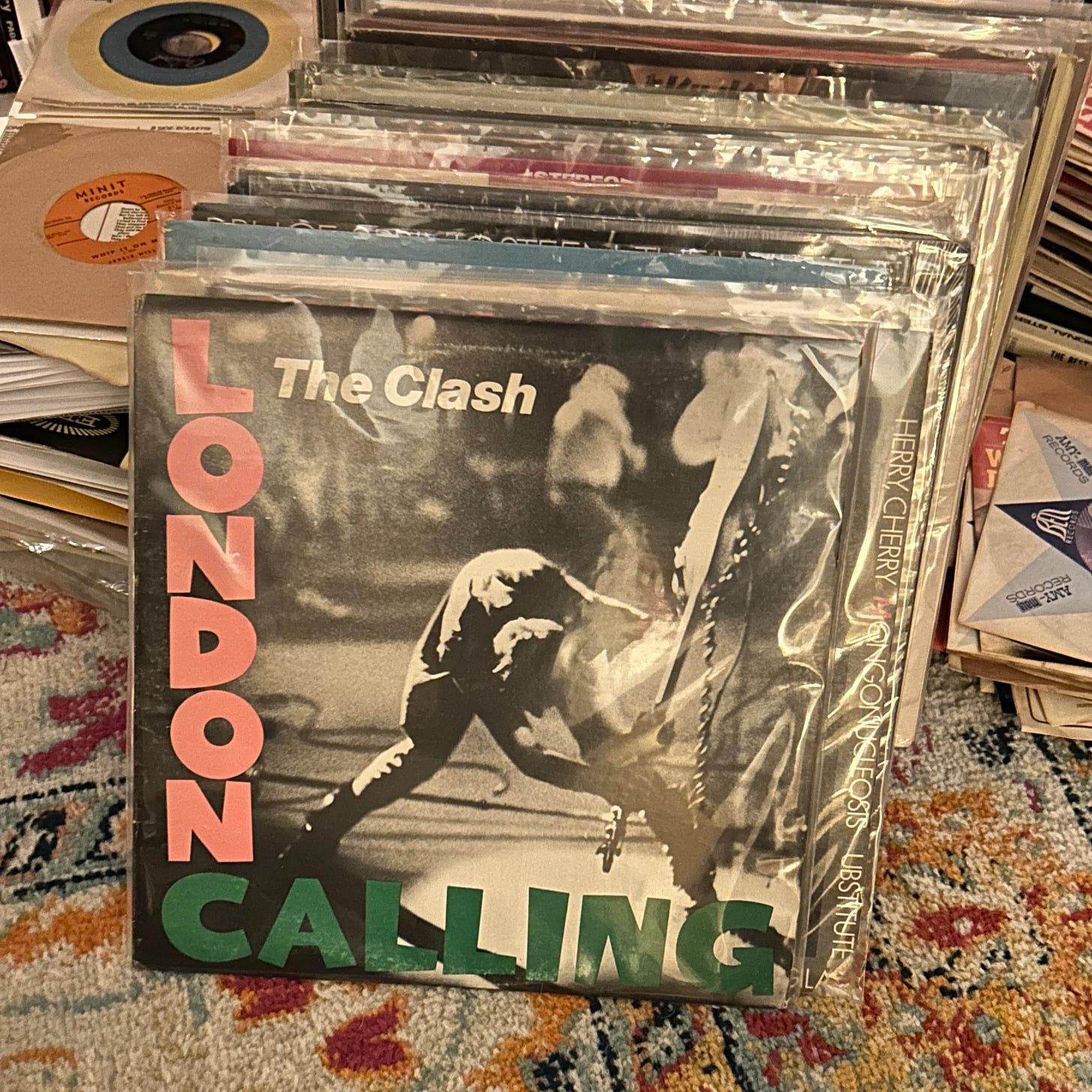

Though I’d never heard the song before, I didn’t need a back-announcement from the station’s DJ to know what it was — I’d seen posters for The Clash’s London Calling album plastered all over Manhattan that summer, all of them emblazoned with the unforgettable image of a guy swinging his guitar like John Henry swung his steel-drivin’ hammer. As the song blasted out over the sand, I was suddenly seized by a feverish vision of an entire chain gang of identical figures slamming their instruments to the ground together in time to the music.

Originally released in December 1979, and coupled with a video of the band performing on the Thames in the freezing rain, “London Calling” was anything but a summer song. And yet, I would never be able to hear it again without feeling the July sun on my shoulders and smelling a faint whiff of salt air, sweat and sunscreen.

So this was real punk rock, I thought to myself. I’d known of the term for years, going back to late 1977 when my fifth grade classmate Johnny excitedly told me about a new British punk band called The Sex Pistols. “They all piss in a big bowl at their concerts,” he swore. “And then the audience drinks it!”

All of which sounded pretty intriguing to me; but as Johnny was rather prone to exaggeration, I wasn’t entirely sure I believed him. (He’d already claimed for months to be in possession of “a photo of Gene Simmons eating out a girl,” yet never actually shared it with any of us.) Then again, the first few self-identifying “punk” songs I’d heard over the next few years on The Dr. Demento Show — stuff like “Punk Polka” by The Toons, “My Beach” by The Surf Punks and “(Your Love is Like) Nuclear Waste” by The Tuff Darts — made it sound like John’s Sex Pistols story had at least one boot in reality.

I knew that Max’s Kansas City, the legendary NYC nightclub that sat kitty-corner across Park Avenue South from my dad’s apartment building, was a “punk club,” and I’d already spent many late nights in the summer of ‘80 looking down from the living room window of his 11th floor loft and observing the comings and goings of Max’s clientele — but I still had only the vaguest idea of what the punk rock bands that these people were going to see actually sounded like. I also knew that some of the “new wave” bands I liked, bands like Blondie, The B-52s and Devo, had played at Max’s before they were famous. But did they qualify as punk? I wasn’t sure.

I was absolutely certain that The Clash were a bonafide British punk band; how could they not be, with a name like that? And yet, the Clash song that marched across Jones Beach to me that summer afternoon didn’t seem wildly anarchic or gratuitously obnoxious, the two qualities that I thought were supposed to signify punk rock. This was a stirring, defiant, well-constructed, guitar-driven rock anthem not a million miles from “Badlands,” one of my favorite Bruce Springsteen songs at the time. (I would learn a few years later that both “London Calling” and Springsteen’s “Roulette” were inspired the March 1979 nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island.)

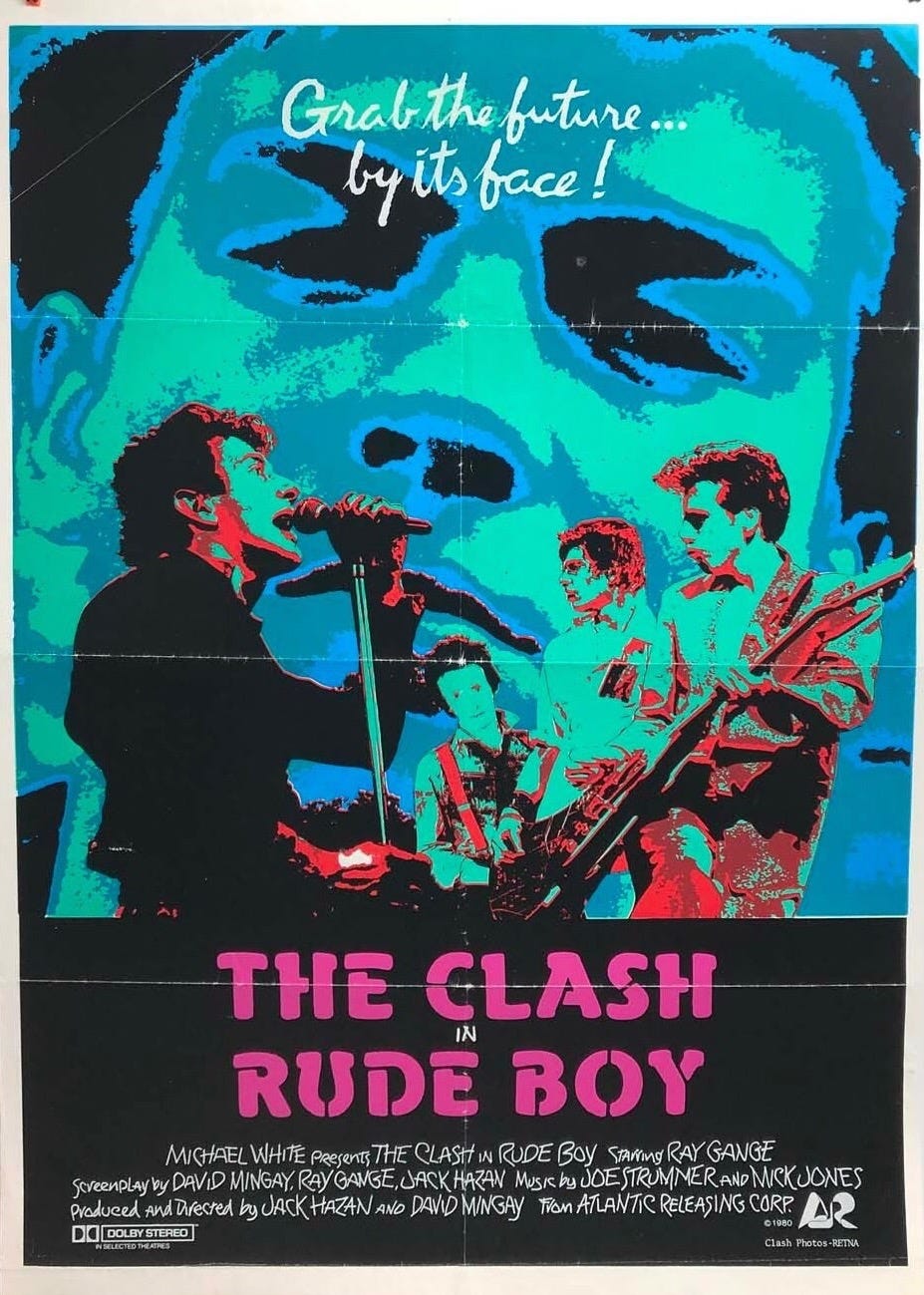

I’d also seen posters around the city that summer for a new film called Rude Boy, posters which featured The Clash and the none-more-punk tagline of “Grab the future… by its face!” As hilarious as that motto was —even at the time, it read to me like a Madison Avenue vision of “punk attitude” — I loved the energy coming off the poster, and thought The Clash looked cool as hell on it.

(I wouldn’t see the film until 1982, and found it an absolute chore to sit through, even if the thrilling footage of the band at the 1978 “Rock Against Racism” concert in London’s Victoria Park kept Rude Boy from being a total disaster.)

Two arresting images and one brilliant song — that’s all it took to make me a Clash fan. When I got back to Chicago in the fall, I taped London Calling from a friend (the 19-song double album was priced as a single, but I was already trying to save up my allowance for The River) and The Clash officially became my first punk band.

From what little I’d read about The Clash in Rolling Stone and elsewhere, I knew they had a reputation for being “political” — though as with my preconceived notions about what a punk band would/should sound like, London Calling massively expanded my understanding of what politically-charged music could be. Because while Joe Strummer clearly had a way with a snappy aphorism (“He who fucks nuns will later join the church” from “Death or Glory” being a personal favorite if mine), the album’s lyrics didn’t limit themselves to easy sloganeering or hurl attacks at specific politicians or political parties.

Instead, they cast the net wide while simultaneously keeping things on a human scale. The songs of London Calling covered everything from nuclear meltdowns, police brutality and terrorist bombings to drug addiction, urban alienation, and the pressure on young people to shut up and conform to societal expectations. These were heavy subjects, and yet — with the exception of ominous rumble of Paul Simonon’s “The Guns of Brixton” and “The Card Cheat,” Mick Jones’ melodramatic Dylan-meets-Spector valediction to British colonialism — the album fairly bubbled with joie de vivre. Love, sex (not just with nuns!), friendship, dancing and celebration were all in the lyrical mix, as well, and their presence made the heavy stuff hit that much harder.

Stylistically, the music was cheerily all over the place, fusing punk with hard rock, R&B, ska and reggae as the band (with the encouragement of legendarily loony producer Guy Stevens) pushed the boundaries of their instrumental and songwriting abilities. The straight-ahead 1950s British rock n’ roll of Vince Taylor’s “Brand New Cadillac” rubbed sideburns with the stoned music-hall goof of “Jimmy Jazz,” and the woozy Montgomery Clift salute “The Right Profile” stumbled face-first into the wistful pop of “Lost in the Supermarket,” in which a heartrending portrait of tower-block loneliness was offset by such note-perfect Strummer-penned, Jones-sung asides as, “I empty a bottle/I feel a bit free.”

The message was clear to me, even back then — no matter how bleak things looked, no matter how hard the bastards tried to grind you down, you fought back by creating your art, speaking your truth, reveling in your existence to the fullest, and finding solidarity and common ground with other like-minded human beings. (“I’ve been beat up/I’ve been thrown out/But I’m not down,” sang Mick Jones on “I’m Not Down,” an underrated track tucked away in the middle of Side Four.) But I was also inspired by how perfectly Jones’ shyly soulful vocals meshed, counterpointed and traded off throughout the album with Strummer’s rebel bark — an unusual combination that was a big part of what made The Clash special, and which telegraphed the idea to me that it was always better to confront a problem with the help and support of a trustworthy partner or partners.

Of course, that beautiful Jones-Strummer partnership had just a few more years to run at this point, but it — and London Calling, along with their first two LPs and (as

and I discussed last year on our CROSSED CHANNELS podcast) parts of Sandinista! — nonetheless left a major mark on me. Maybe too much of one; back in 2022, when I was winnowing down my album collection during the run-up to my move from NC to NY, my Clash LPs all went into the “Sell” pile. Not because I didn’t love them anymore, but because I’d listened to them all so many times in my teen years that they were practically embedded in my DNA; at this point, I could hear every note of those songs without actually putting the records on. Plus, I needed the cash — and since none of those albums were exactly rare, I figured they’d be easily found if I ever got the urge to hear them again.Maybe it was due to the fascist shit-show that’s been befouling my country, but a few months back I started really craving a new copy of London Calling. Finding an original pressing in decent shape at an affordable price proved harder than I expected, however, and it was only last week that the new/old copy of my dreams finally arrived. Just seeing it back by my stereo again gave me an unexpected lift, but being able to blast it on my turntable for the first time in years also provided a much-needed spiritual boost. “Clampdown,” one of the album’s many highlights, sounded especially timely in light of the recent canonization of a deceased white supremacist podcaster, along with the present administration’s giddy rush to use his horrific murder as a Horst Wessel/Reichstag Fire-like excuse to seize more power.

We will teach our twisted speech

To the young believers

We will train our blue-eyed men

To be young believers

Strummer’s lyrics hit me even harder the other night after hearing the news about ABC bending the knee in response to the administration’s most recent “Nice network ya got here, shame if something happened with your impending merger” mob-boss extortion campaign, this one targeting another network that’s been on Dear Leader’s hit list because a comedian dared to make fun of him on late-night television.

The voices in your head are calling

Stop wasting your time, there's nothing coming

Only a fool would think someone could save you

The men at the factory are old and cunning

You don't owe nothing, so boy, get running

It's the best years of your life they want to steal

This latest shameful display of corporate compliance was deeply disgusting, and understandably caused a huge outcry on social media that included expressions of hopelessness and despair at our country’s descent into 21st century McCarthyism. But listening to London Calling again reminded me that just giving up or “going along to get along” are not viable options in these dark times. Knuckle under to these knuckle-draggers, and they’ll never let you back up.

So you got someone to boss around

It makes you feel big now

You drift until you brutalize

Make your first kill now

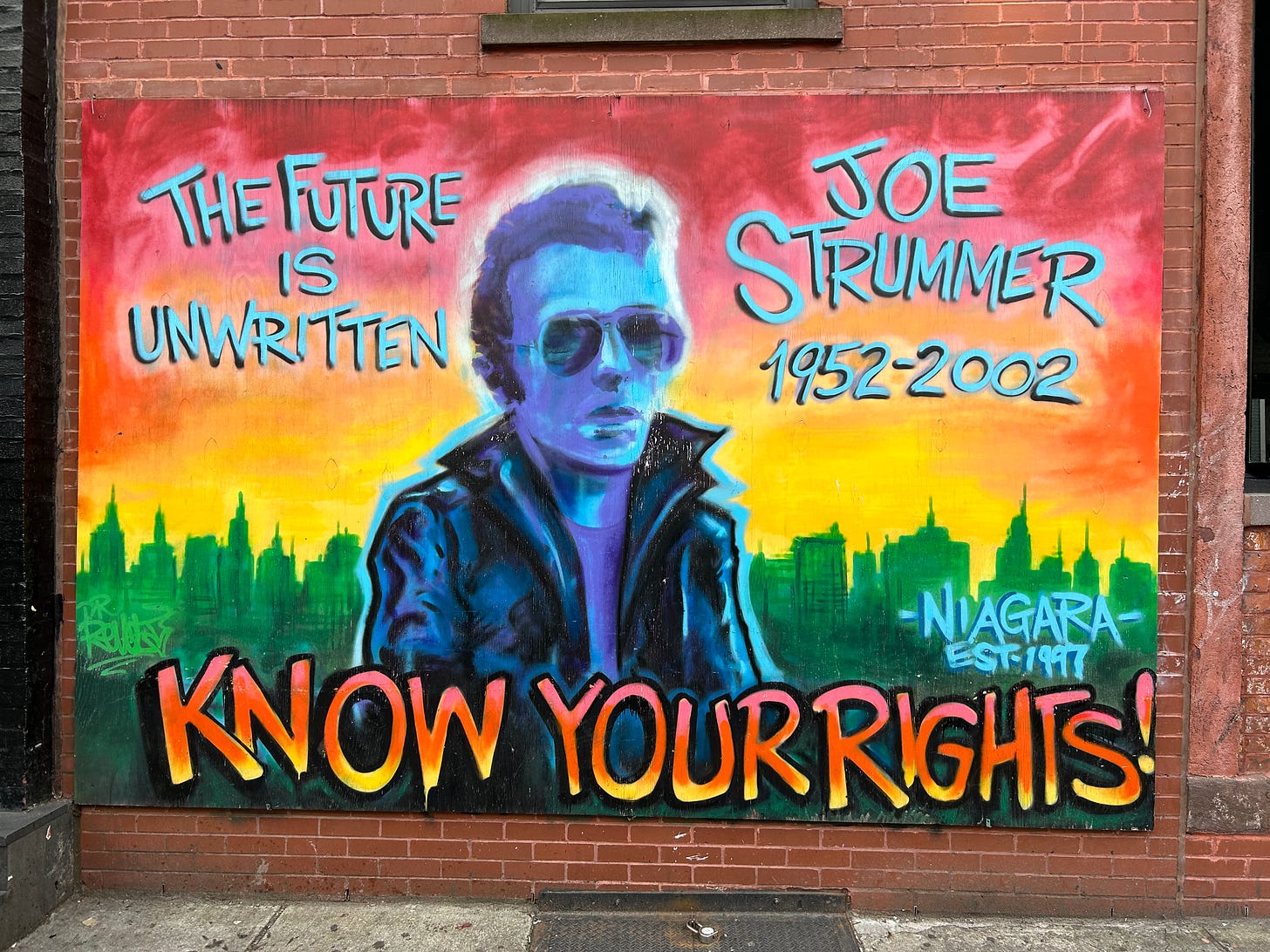

“The future is unwritten,” proclaimed the late, great Joe Strummer. Listening to London Calling again some 45 years after I first heard the album, it occurred to me that if he were still here he’d be insisting that we stick together, stay hopeful, speak out loudly, and push back hard with a song on our lips — and reminding us that giving a playground bully our lunch money will achieve nothing beyond bringing them back for more.

Kick over the wall, cause governments to fall

How can you refuse it?

Let fury have the hour, anger can be power

Do you know that you can use it?

Long Live The Clash. Long Live Joe Strummer. And Fuck Fascism Forever.

Though it's not on London Calling, another Clash lyric came to mind this week due to Trump's state visit (urgh) to the UK:

If Adolf Hitler flew in today

They'd send a limousine anyway

Brilliant 🥲