And I'll Do Unto You What You Do To Me

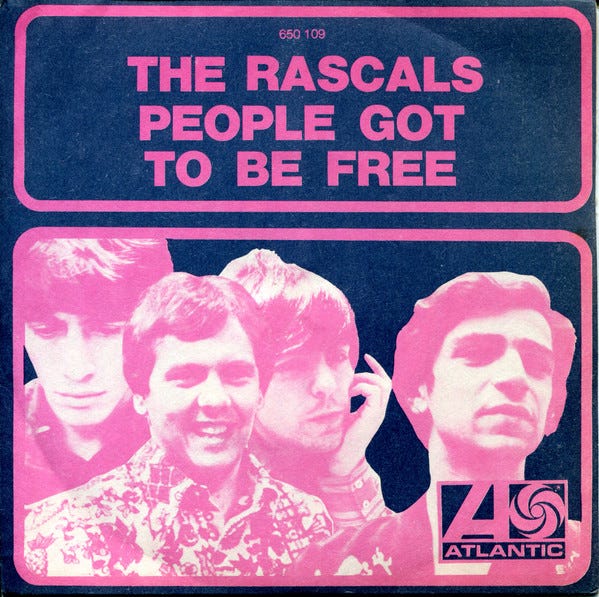

The Rascals — "People Got to Be Free" (1968)

“People Got to Be Free,” the chart-topping 1968 single from The Rascals, never failed to crack Ron up. “Oh yeah, they got on board, all right,” he’d invariably mock, whenever Felix Caviliere would unleash his exultant cry of “Get right on board, now!” I loved the song, and its message of brotherhood and understanding, but Ron always made it clear to me that he saw “People” merely as a craven attempt to cash in on the prevailing flower-power vibe. He’d been in college during that era, whereas I’d only been a toddler, so I chose not to argue the point. But his opinion left a bad taste in my mouth that I could never quite shake…

Ron dated my mom for a few years back in the mid-Eighties, and he was always my favorite of her post-divorce boyfriends and partners, in part because he had an amazing record collection which he was incredibly generous about letting me explore. That his presence in our lives happened to coincide exactly with the period of my life in which I’d become seriously obsessed with the pop, rock and soul music of the 1960s was a bonus; he’d actually heard all these great records in real time, bought mod clothes at hip Chicago haberdasheries like The Man at Ease, and watched bands like The Jefferson Airplane and The Iron Butterfly in concert at local venues like the Aragon Ballroom and the Kinetic Playground. Like his records, Ron was more than happy to share his memories of that time with me — and I was all too happy to listen.

I got to thinking about Ron and his Rascals riff yesterday, when “People Got to Be Free” popped up on my favorite station WIWS right as I was heading to the market. I remembered taping his copy of Time Peace: The Rascals’ Greatest Hits, and complaining because “People Got to Be Free” wasn’t included on it. (I would later learn that the single had been released on July 1, 1968, a week after the album came out.) “Why would you want that one on there?” he scoffed. “This is all the Rascals you need.” Still, he was kind enough to dig out some compilation or other that had “People” on it, so that I could add the song to the end of my TDK SA-90 cassette.

Recorded about six weeks after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, and reportedly inspired by an ugly incident in Florida in which the band had been harassed by local rednecks for having long hair, “People Got to Be Free” certainly touched a national nerve. It spent five weeks that summer atop the Billboard 100, reached #14 on Billboard’s Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles chart, and wound up as Billboard’s fifth biggest single of 1968. But there were also a lot of longhaired folks like Ron who, despite essentially being on the same side as The Rascals, saw the song as little more than a lame joke.

Sure, “People” Got to Be Free” didn’t offer much in the way of solutions beyond recommending that we should try to look beyond our differences and promising that “I’ll do unto you what you do to me” — but then again, The Youngbloods’ 1967 recording of the much-loved hippy anthem “Get Together” (which wouldn’t become a massive hit until 1969) was equally vague on specifics.

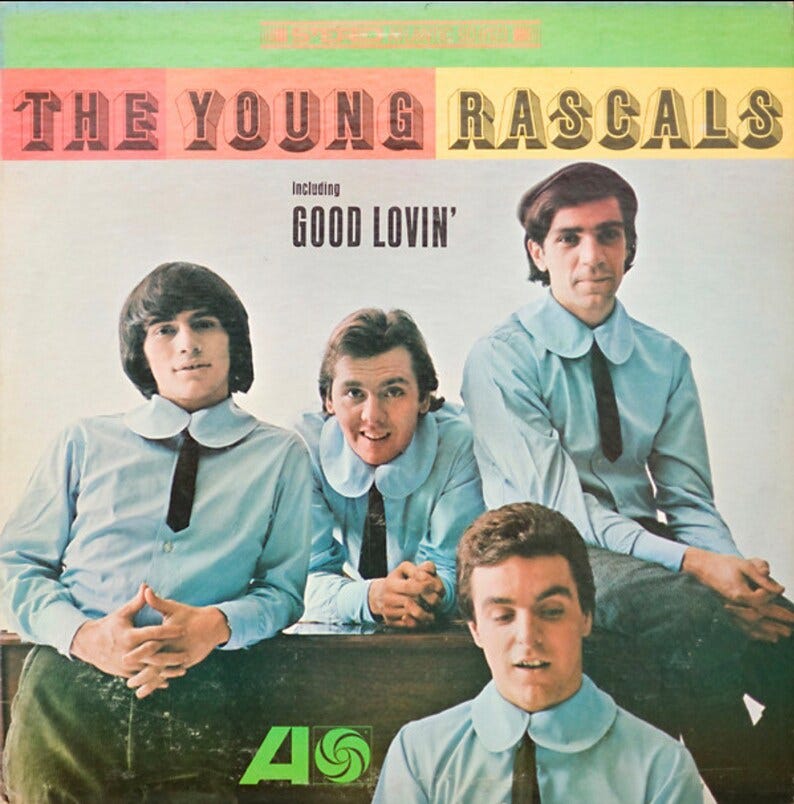

No, the problem for Ron and a lot of other folks who considered themselves particularly “right-on” at the time wasn’t the message, but rather the messenger. The Rascals weren’t lentil-lapping Haight-Ashbury denizens who’d paid their hippy dues; they were four pizza-fortified Italian dudes from New Jersey and New York who just two years earlier had been jamming on “Mustang Sally” and “In the Midnight Hour” at a floating nightclub in Long Island while dressed like Little Lord Fauntleroy. Hell, they’d just jettisoned the “Young” from their name a few months before “People” was released. How could you possibly take them seriously in their beards and love beads?

The Young Rascals in early 1966… and The Rascals in the summer of ‘68.

Now, I wasn’t “there” at the time it originally hit the radio waves, but “People Got to Be Free” has never felt phony to me; nor has it — like, say, Eddie Fisher’s cover of “The Fool on the Hill” — ever sounded to me like the work of squares wrapping themselves in the paisley caftan of psychedelic opportunity. Listening today, the song still strikes me as the sincere work of four talented if not particularly eloquent dudes who felt like there was something that needed to be said, and knew they had a platform with which to say it. And I still don’t have a problem with any of that.

I did, however, find myself wondering how “People Got to Be Free” — which as far as I know is still a staple of oldies stations everywhere — falls upon contemporary ears. Does it still inspire and uplift? Does it come across as just another “freedom rock” jam, another cheerful-but-toothless oldies artifact from a time that promised so much and ultimately delivered so little? Does it cause the descendants (both literal and spiritual) of those aforementioned Florida rednecks to grind their molars over its “woke agenda”? I mean, if some people are freaking out right now about the “rainbow” on the 50th anniversary edition of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, who knows what they’d make of a song that preaches peace and tolerance while suggesting that the man “who is down and needs a helping hand” should actually be given one, instead of being forced to pull himself up by some imaginary bootstraps…

Me, I still find that “People Got to Be Free” delivers a little much-needed light in the darkness, and even more so in this smoking vintage clip of The Rascals performing the song in front of a tambourine-loaded studio audience. Sure, Felix Cavaliere and Eddie Brigati’s dueling Maharishi beards are pretty goofy, but the band isn’t messing around — and any chance to watch the late, great Dino Danelli in action on the drums should absolutely be taken, regardless of how you feel about the song.

Ask me my opinion, my opinion will be: “People Got to Be Free” kicks ass, and so did The Rascals.

Ron was just another one of those elitist Love Gen' assholes, who were as much creatures of their own prejudices, as any of the rest of the planets unevolved occupants. As I recall, "The Young Rascals" were a product of the record label - at least in their style of dress and physical presentation. After the "incident" in Florida aka The Land That Was/Is Lost In Time, they said a collective Peeleian "Nope" and came out of the closet to reveal who they really were to the world. This isn't surmise on my part, it's strong personal recollection of one of the three happiest/saddest periods of my life. My father owned a successful record business on Dexter Avenue, and we were always making runs over to Motown Records which was a hop, skip and a jump away. Right next door was Bishop's Barbershop where the local area performers and musicians had their haircuts and conk jobs done. Where Black Detroit Tigers baseball team members like Gates Brown and Willie Horton hung out when they weren't on the road. That 3 block stretch of Dexter Avenue also included the Safari Club (where my father's slide into the family plague first began) and the Dexter Bowling alley where I saw my first "street murder" - a near beheading by machete over a crooked dice game. It was a hotbed for the hottest topics of the time in the neighborhood - Motown and it's competitors, the Tigers and how their Black players had helped shift the balance of power away from the B'more Orioles and Frank Robinson, and the rising tensions in the inner cities of America as a result of the burgeoning social freedom/civil rights/anti-war movement. In that situational cultural context, the transformation of the Young Rascals into The Rascals wasn't perceived to be phony. Hell, Black America looked at the Hippie movement as phony because we didn't see it offering any direct substantive political support to our critical concerns of the era. Their transformation, as seen thru the critical social lenses available to my ears and eyes, was just something "that shoulda always been" as my father used to like to put it whenever something unreal got real.

Dan, always a treat to read your experiences with the music I also grew up with. Was struggling with a slide rule and matrix algebra as an engineering student in '68. Great to hear things about your familial past.