Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere

Making Time for 10 classic Shel Talmy-produced tracks

Despite enjoying a career that lasted over six decades, Shel Talmy’s name always conjures up a very specific time and sound for me: The biff bang pow of mid-sixties mod pop.

I first saw the producer’s name on the back of The Who’s My Generation LP — or was it The Kinks’ Greatest Hits? Either album would have been sufficient to make Talmy (who sadly passed away last week at the age of 87) synonymous in my mind with bracing blasts of guitar-driven bliss launched by arrogant, impeccably-dressed London lads.

Though largely recorded on the cheap, the singles and albums Talmy produced for those two bands possessed a visceral immediacy and intimacy, like they were teleporting you into the studio right as the song was being tracked. Not coincidentally, both The Who and The Kinks are bands with whom their ardent fans (such as myself) feel an incredibly deep personal connection. Along with the songwriting of Pete Townshend and (especially) Ray Davies, I’d wager that said immediacy and intimacy of Talmy’s production work played a significant part in fostering that sense of recognition, that life-affirming jolt of “Yes — this is my band!”

Of course, as writer/musician/historian Alec Palao wrote in this lovely remembrance, there was far more to Talmy’s life and work than those remarkable mid-sixties Kinks and Who records. After attending L.A.’s Fairfax High School (where he graduated two years after Herb Alpert and two years ahead of Phil Spector), Talmy initially wanted to be a film director, but ditched his celluloid dreams in favor of music once the genetic eye disease Retinitis Pigmentosa began to rob him of his vision. Talmy’s ears never failed him, however; and though he initially bullshitted his way into a production gig for the London-based Decca label in 1962 — the brash young Californian played an acetate of The Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ Safari” for Dick Rowe, the label’s head of A&R, pretending that he’d produced it — Talmy quickly proved that he had more than sufficient skills (and pop sensibilities) to justify his place in the British music industry.

In the wake of Talmy’s passing, I wanted to honor him here at JTL by sharing a list of ten favorite songs that he produced, but it quickly occurred to me that I could easily just pull ten (or even twenty) favorite tracks from the small batch of Talmy-helmed Kinks albums that ran from their self-titled 1964 debut to 1966’s Face to Face. So in order to zooming the lens out a bit, I’m pulling my choices here from a wider array of artists (while still giving my beloved Kinks a couple of spots), and listing them in chronological order.

As mentioned in Palao’s remembrance, Talmy was a regular presence (and a delightful follow) on Facebook for years; with Palao’s help, he posted fascinating reminiscences about certain recordings, often getting very deep into the technological nitty-gritty. I’m hoping that Palao will eventually collect these posts in some sort of book, but I’ll quote from some of them here where applicable.

The Kinks — I Need You

Arguably the greatest Kinks B-side of all time (it was slapped on the back of their wistful 1965 hit “Set Me Free”), “I Need You” is my personal favorite from the band’s Talmy-produced string of hard-riffing early tracks that began in 1964 with “You Really Got Me”. Dave Davies’ snarling feedback intro — and the fact that at least one guitar is noticeably out of tune — lends the track a glorious sense of proto-punk don’t-give-a-fuckness, and the whole thing crunches like a transit van attempting to batter its way through a warehouse wall.

“We recorded this at the larger Pye #1 studio on the 13th and 14th of April, 1965, with Bob Auger the engineer,” Talmy recalled. “The players were the classic line up of Ray on lead vocal and rhythm guitar, Dave Davies on lead guitar, Pete Quaife playing the bass and Mick Avory the drums. Dave and Pete did the backing vocals, joined by Ray’s wife Rasa… we were still recording straight to mono. After we got the master, I had Dave double the barre chords to beef up the sound. The result was one of the band’s best early rockers.”

And it was apparently recorded only two weeks before this next one…

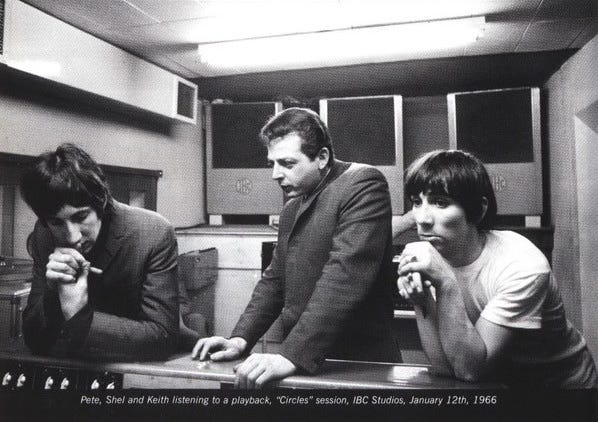

The Who - Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere

It’s so hard to pick a favorite from that initial burst of Who tracks that they recorded with Talmy — basically the My Generation LP plus a handful of non-album cuts — before falling out with the producer, but this 1965 single qualifies for inclusion here on the basis of Pete Townshend’s clanging Rickenbacker chords, his then-radical (and still thrilling) feedback break, Keith Moon’s anarchic drumming, and the hopped-up ivories-tinkling of session pianist Nicky Hopkins.

(Speaking of which: I rented the Hopkins documentary The Session Man on Apple TV the other night, and was really frustrated by it. Hopkins played an incredibly important role in the history of rock and roll, but his musical contributions deserve a smarter and far more detailed salute than this artless Tubi-level mishmash could manage. I want my four bucks and 90 minutes back.)

“In retrospect, while ‘Can’t Explain’ was a very successful commercial release, ‘Anyway’ was closer to how the band really sounded,” wrote Talmy, “and it became the track that established The Who as an act whose dynamic live performances could be captured on tape.”

Davy Jones and the Lower Third — You’ve Got a Habit of Leaving Me

Talmy brought Nicky Hopkins back to the studio for a July 1965 session with a talented 18 year-old singer-songwriter named Davy Jones, who would become much better known under the moniker of David Bowie. Though far from Bowie’s best work, I love the way this song’s callow, almost naive melody suddenly explodes into a Who-esque freakout, with guitarist Denis “T-Cup” Taylor bashing out the distorted power chords. “Habit” was one of several tracks the future Mr. Bowie recorded with Talmy, though none of them managed much in the way of chart success.

The Creation — Making Time

By 1966, Talmy had enough cachet in the British music industry to launch his own record label, Planet Records. The Creation, a brilliant and kinetic mod quartet from Chestnut, Hertfordshire, should have been the label’s breakout band, but a frustrating combination of distribution issues and lineup changes prevented them from achieving any major success.

I recall reading about The Creation years before I ever actually heard anything by them, intrigued by stories of guitarist Eddie Phillips’ use of a violin bow — Jimmy Page apparently nicked the idea from him — and of their violent stage act that occasionally featured lead singer Kenny Pickett spray-painting pop art canvases onstage and then lighting them on fire. (Their motto “Our music is red — with purple flashes” is also still pretty much the coolest thing ever.) I finally heard “Making Time” in 1986 after tracking down a French compilation of the band; suffice to say it was worth the wait.

“I loved the track because it was loud, ballsy, melodic and had a secret weapon that was brand new and original — Eddie played the guitar with a violin bow, producing a unearthly but melodic screeches!” Talmy later recalled. “We were convinced ‘Making Time’ was gonna be a huge hit, but I didn’t count on my distributor, Philips Records, doing absolutely nothing to promote the record, when they had “promised” to do the opposite... Another lesson learned regarding when trusting labels to do what they say they are going to do, and the main reason that I folded Planet Records in so short a time.”

The Kinks — Too Much On My Mind

It wasn’t all slam-bang mod pop action for Talmy, though. This moody, harpsichord-laden track (Nicky Hopkins again!) from Face to Face remains one of Ray Davies’ finest moments of introspection; and while Talmy would part ways with the band soon after, following the sessions for 1966’s “Dead End Street,” it can certainly be argued that his production work on this LP helped put The Kinks on course for their incredible run of late-sixties and early-seventies albums that followed.

The Thoughts — All Night Stand

Speaking of Ray Davies, “All Night Stand” was written by the Kinks leader at Talmy’s request, as the theme song for a mooted film project based on Thom Keyes’ lurid novel of the same name. Though the film was never made, Talmy produced two versions of Davies’ moody tune as recorded by Liverpool mods The Thoughts; this one was released in the UK in September 1966 via Planet Records, and features some acoustic 12-string overdubs by legendary British session guitarist Big Jim Sullivan.

The Easybeats — Friday on My Mind

As great as Talmy’s work was with the Kinks, Who, Creation, etc., one could argue that this worldwide smash for Australia’s Easybeats was the most perfect track he ever cut. It just grabs you from the opening notes and refuses to let go, while the arrangement’s brilliant use of tension and release completely captures the tantalizing excitement of a weekend looming into view.

While brilliance of the song and performance was all down to the band themselves, Talmy was savvy enough to recognize a hit when he heard it — “I think they were literally about eight bars into it when I said, ‘Yes!’” he later recalled — and to let the Easys do their thing in the studio without getting in the way. “As the group was very well-rehearsed, we got the ‘master’ on the 3rd take,” he remembered. “‘Little Stevie’ [Wright], who had excellent microphone technique, then added his lead vocal, while Harry Vanda and George Young did the backing vocals.”

Sadly, the band’s management completely screwed Talmy out of his producer’s fee and any related royalties, but his name will still be forever associated with this three-minute blast of power pop perfection.

The Creation - Nightmares

All too often overlooked in the discussion of The Creation’s small but mighty discography, 1967’s “Nightmares” — the flip side of “If I Stay Too Long” — is one of my favorite things they ever waxed. Recorded after a six-month studio hiatus (original singer Kenny Pickett co-wrote the track based on a presumably bad acid trip, but had been replaced on lead vocals by original bassist Bob Garner by the time of recording), “Nightmares” features some wonderfully atmospheric production touches from Talmy, including the brilliant layering of Eddie Phillips’ aurally unsettling guitar noises.

Bert Jansch — Poison

Of course, Talmy wasn’t just adept at capturing freaky electric guitar experiments; as proven by his work with folk-rock outfits The Pentangle and The Sallyangie, he could also record the living shit out of an acoustic guitar. Just listen to this highlight from Birthday Blues, the 1969 solo album by legendary folk guitarist (and Pentangle co-founder) Bert Jansch — it has such a haunting vibe and alluring sound that I wish it ran at least twice as long.

The Pentangle — Light Flight

Talmy produced the first three albums by British folk-rockers The Pentangle, the last of which, 1969’s Basket of Light, included this jazzy number. Penned by the group as the theme for the BBC TV series Take Three Girls, “Light Flight” was, in Talmy’s words, “a complicated piece of music that was extremely commercial!”

Influenced by the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Take Five” — but utilizing passages in 5/8, 7/8 and 6/4 time instead of aping that song’s 5/4 signature — “Light Flight” showcases the brilliant interplay of guitarists John Renbourn and Bert Jansch, upright bassist Danny Thompson and drummer Terry Cox, while Jacqui McShee holds the whole thing together with her stunning vocals.

Of course, there’s so much more to the Shel Talmy discography — Chad & Jeremy! Manfred Mann! Roy Harper! Wild Silk! Amen Corner! Lee Hazlewood! The Damned! etc. etc. — and I could easily rattle off thirty to forty other tunes he produced that I’d consider absolutely essential. The man unquestionably left his mark, both on my brain and on popular music in general.

Rest easy, Shel. Thanks again for all your great work.

Eddie Phillips! Holy shit, what a great find Dan, I was not hip, and it did ring a bell about Page nicking it from someone, somewhere. Also was not hip to “I Need You” - love it! The whole ‘set’ is nicely done, what a lovely way to spend a lazy Sunday morning.

Finally able to come up for air after the election, I just had to say how much I loved this post and songs! Other than the Easy Beats’ song, I hadn’t heard any of the others before. Wow, thanks for the pick me up!