But Definitely For Me

How Ahmad Jamal opened my mind and ears to jazz

During my five years before the mast — er, I mean, behind the record store counter — I generally strove to be the opposite of the haughty, obnoxious, cooler-than-thou record store clerk stereotype I first experienced at NYC’s House of Oldies when I was 12, and encountered again and again throughout my teens. As a music lover, I wanted to send the customer home with something that they really wanted to hear, and maybe even introduce them on to something awesome that they didn’t even know they wanted.

Which is not to say that I wouldn’t tell you the truth if you asked me, “How’s the new Blues Traveler?” Or that I would go out of my way to help you if you were rude to me or my fellow employees. But if you acted like a normal human being and weren’t completely dead-set on buying whichever mediocrity WXRT had played shortly before your lunch break, I would happily try to help you broaden your musical horizons — especially if you were interested in, say, the noisier realms of alternative rock or the funkier pastures of ‘70s soul, or even if you were just a denim-clad adolescent stoner from the school down the street grappling with which Rush album to buy first (“2112 is the one you want, son”), I took pride in the fact that I could come up with a winning recommendation for you.

Metal, rap, country, oldies, easy listening, soundtracks, vocal standards — if that’s where you were coming from, I could get you where you wanted to go. I could usually identify the song you were looking for if you sang me the melody (I once got a kiss on the cheek from a sentimental lady for leading her to the Bob Welch tune of the same name), and I could often guide you to the record you wanted even with the most minimal of clues. (“Man, you got that record by that young girl?” “Tracie Spencer? Yeah — right over there.”) Three decades later, I still occasionally get messages from former customers I became friends with, thanking me for turning them on to Hound Dog Taylor, or The Chi-Lites, or Monster Magnet, etc., which makes me feel like I haven’t completely wasted my time on this planet.

My one serious musical weak spot in those days, however, was jazz. With the exception of some early exposure to the music of Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton (The Sting soundtrack had piqued my interest in ragtime) and a basic jazz primer from the African-American Music History course I took in college, I really knew or understood very little about it. In retrospect, I blame exposure to WXRT’s fusion-intensive Sunday night program Jazz Transfusion for short-circuiting any interest my high school self might have otherwise had in exploring jazz; I mean, you can really only be inundated with so much Jean-Luc Ponty before you finally go, “Eh, this stuff isn’t for me.”

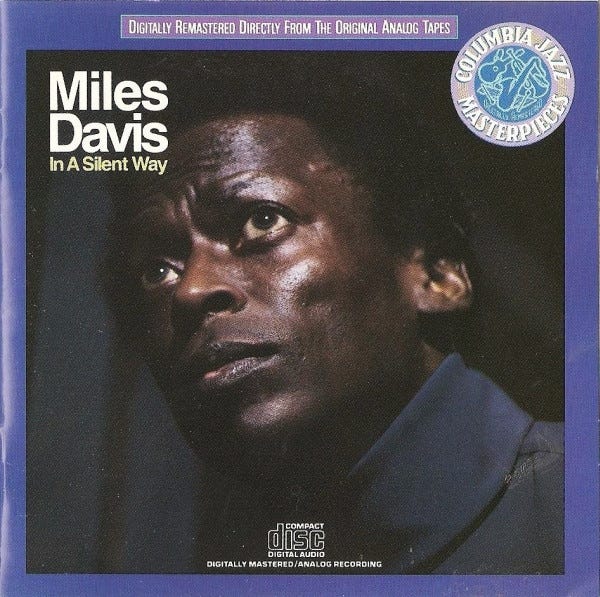

So while I understood that Miles Davis and John Coltrane were groundbreaking artists in the field — and that they were way more appealing to me from an aesthetic standpoint than, say, Kenny G or The Rippingtons — I remained pretty clueless as to their respective discographies. I still cringe at the memory of a woman in her sixties who came in to See Hear and asked me to pick out a Miles CD for her that was “quiet and mellow, like Kind of Blue”. I sold her In a Silent Way — a record I’d never actually heard — because, you know, “silent”. It’s one of my favorite Miles records these days, though “quiet” or “mellow” aren’t exactly the first adjectives that leap to mind. (Maybe she dug it anyway; at least, she never came back to complain.)

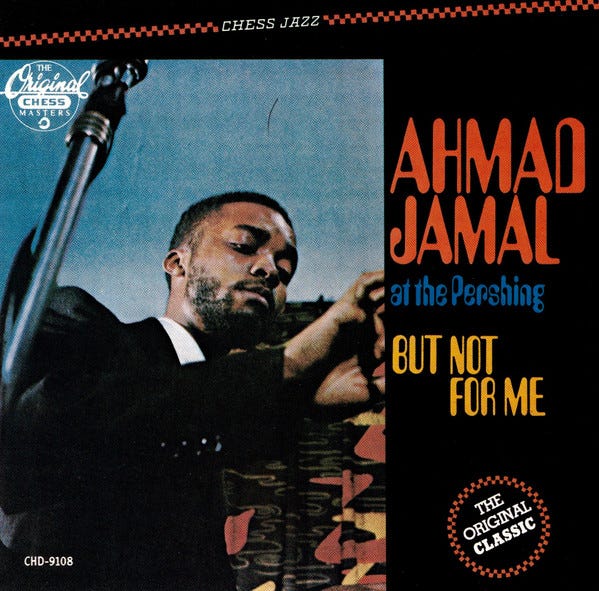

But there was one jazz album we moved a lot of that always kind of caught my eye: The Ahmad Jamal Trio’s At the Pershing: But Not for Me. Everything about the cover — from the title to the Great American Songbook-intensive track listing to the elegant portrait of the artist at work — just radiated “class” to me. (Or “clayse,” if you’re from certain parts of Chicago.) I was deeply intrigued, yet somehow couldn’t quite pull the trigger on purchasing the CD for myself. We sold at least a couple of copies a week, and I always kind of half-hoped that someone would return one, just so I could pop it into the store player and hear what it sounded like, but that never happened.

Finally, in the fall of 1992, I got my chance. I’d moved out of my band’s house a few months earlier, and our drummer Anthony had moved in to take my place. Anthony had much broader musical tastes — or at least a much broader record collection — than the rest of us, and I’d often pick his brain whenever I developed a new interest in something like Martin Denny, Esquivel or Astrud Gilberto. Though I was no longer a resident, I still had a key to the house, as our gear was in the basement; so if I showed up for practice before everyone else did, I could just let myself in and wait for my bandmates to get home.

On this particular evening, I arrived at the house about an hour or so before the other guys were due to get back from work, so I started looking through Anthony’s CDs for something to listen to while I hung out in the living room. And there it was: Ahmad Jamal at the Pershing! I popped the CD into the living room player, and was instantly transported to a Chicago I’d dreamed of but had never experienced — a Windy City whose downtown was studded with sophisticated jazz clubs, where men and women in well-tailored outfits enjoyed strong cocktails and refined music in plush, dimly-lit surroundings just steps away from the grittiness of Grant Park or the noisy elevated trains of “The Loop”. Here I was, sitting on a ratty fold-out couch in a room with dreary beige carpeting, a dirty two-foot bong and walls decorated with band and film posters, yet this CD made me feel like I was nursing a well-made martini in a tufted leather banquette with a charming and attractive female companion by my side.

The jazz I thought I knew was overly busy and showily proficient, but there was an inviting warmth and space to this music that was in no way compromised or overwhelmed by the precision playing of the musicians. It was playful at times — especially on the arrangement of “Surrey with the Fringe on Top,” a song I was familiar with from having starred in a sixth grade class production of Oklahoma! — yet it was also deeply dignified in a way that I wasn’t used to hearing. Sort of like Jamal was saying, “Yeah, I’ve been through some shit, and I’m going to channel my anger into blowing your mind with some impeccably dazzling musicianship.” And when the CD ended, after a little over a half hour, I hit the “Play” button so I could hear it all over again.

“Wow, it’s really cool that you’re playing this,” I heard a voice from behind me say. It was Anthony, getting home from work. “Yeah, man,” I responded, feeling slightly embarrassed, like I’d been caught with something slightly forbidden. “I hope you don’t mind me digging through your CDs.” “Not if you’re gonna pull out stuff like this,” he chuckled.

And that was really all the encouragement I needed to start dipping my toe into jazzier waters. It’s hard to remember the exact trajectory my jazz journey took from there — though I know Ramsey Lewis, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Sonny Sharrock and Grant Green were all stops I made early on — but it definitely all started with Ahmad Jamal at the Pershing. Upon further research, I learned that the record had sold nearly 50,000 copies upon its initial release in 1958, a massive success by the jazz sales standards of the time, so I’m sure I wasn’t the first listener to find it a “gateway album”.

News of Jamal’s death earlier this week brought the above memories flooding back. While I’m saddened by his passing, there’s no question that the man had an amazing run — 92 years is nothing to sneeze at, especially considering that he was still making new records into his late eighties — and it’s one of those things where I’m just thankful I got to be here for some of the same time as a giant of his stature.

As a friend of mine once wisely noted, there is no such thing as a bad Ahmad Jamal album; just put your finger down anywhere in his discography, and you’ll come up with brilliantly played, deeply felt music that will take you somewhere well worth going. But for me, it always goes back to But Not For Me.

Rest in power, Maestro.

First Clayse writing!

Nice job, Danny Boy!