From the JTL Archives: Some Guy Named Ernie

Talking "That Lady," Jimi Hendrix, and musical stepping stones with the great Ernie Isley

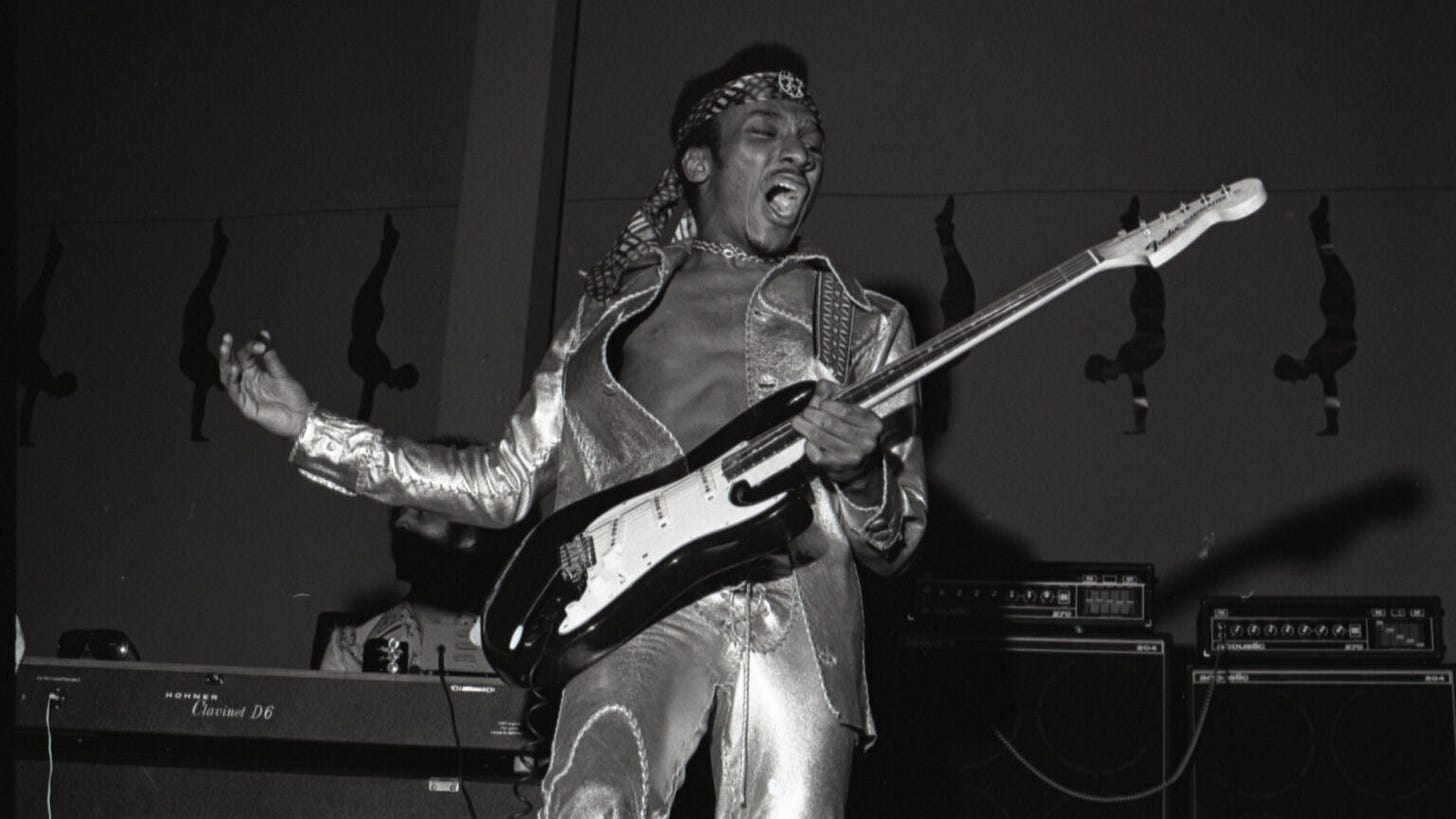

(Photo by Don Hunstein, Sony Music Archives)

Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers!

As some of you already know, I’m neck-deep in the manuscript deadline of a new book project, this one detailing the strange and wonderful history of the Electro-Harmonix company, the fine folks who brought you the Big Muff guitar pedal. Since I don’t have time at the moment to whip up some new things for your reading delight — and since I have guitar stuff on my mind — I thought I’d instead make this post (which was originally sent out to my paid subscribers in February 2023) available to all of my readers.

If you dig these sorts of interviews, I have a ton of them already residing in the JTL Archives, including in-depth conversations with such legendary musical personages as space-age bachelor pad composer Esquivel, Slade frontman Noddy Holder, inimitable bar-band rocker Eddie Money, AC/DC lead guitarist Angus Young, all of which are available to my paid subscribers… as are a dozen or so chapters from my in-progress musical memoir of my turbulent adolescence, and of course all the full episodes of CROSSED CHANNELS, the music I do with my pal and fellow music scribe

. And there’s more of all of this to come once I get past my book deadline; so if this sounds like your cup of meat, please consider supporting this Substack by singing up for a paid JTL subscription at the wallet-friendly price of five bucks a month, or a mere $4.17/mo if you opt for the annual subscription.Thank you for sitting through my sales pitch. Now read on…

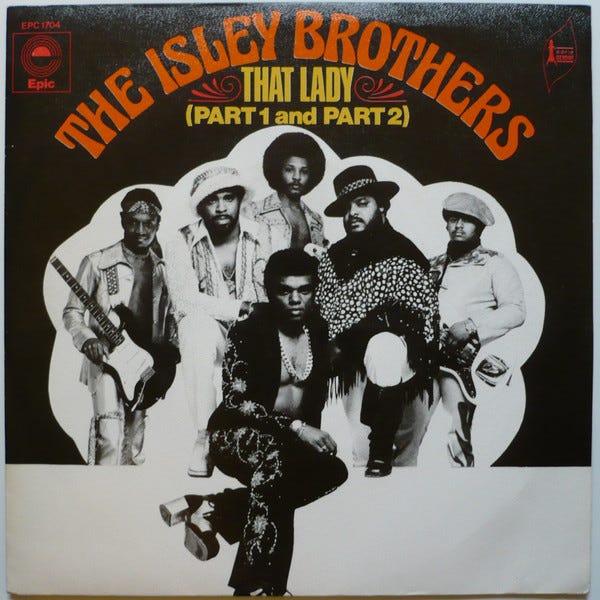

It was the summer of 2001, and I had Ronald and Ernie Isley on the phone. Eternal, the Isley Brothers’ 28th album, was just about to drop, and I was conducting an interview for Rolling Stone about the record, which featured a wide array of contemporary R&B talent — including Raphael Saadiq, Jill Scott, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, and the now-disgraced R. Kelly — pitching in to help bring the soul legends into the 21st century.

Ronald, the older of the two by 11 years, and the only surviving member of the original Isley Brothers trio, had done most of the answering during our chat. But seeing as we had a minute or two left at the end of our scheduled phone call, I decided to direct a question to Ernie, a question I’d been craving the answer to for over a decade.

“So, Ernie… I’ve always loved your guitar sound on ‘That Lady’. How did you get it?”

“Oh, it’s pretty simple,” he began, but Ronald cut him off.

“FAMILY SECRET!!!” the older Isley proclaimed, chuckling as he brought our interview to an end.

Goddammit, Ronald…

Growing up in the ‘70s, I’d been aware of the Isley Brothers, though I definitely wasn’t hip to them. I would always see their latest albums — they released a new one every year back then — riding high on the Billboard charts, but I had no real idea what they sounded like, since their songs didn’t get much if any airplay on the AM pop stations I listened to. While I knew their biggest hits, 1973’s “That Lady” and 1975’s “Fight the Power,” I couldn't have actually told you who sang them; they were just sort of stray aural artifacts from the part of my childhood where I was far more interested in G.I. Joe than I was in music.

My own Isleyfication didn’t occur until well into the ‘80s, beginning with the belated realization that the Brothers had waxed the original hit versions of beloved party anthems “Shout” and “Twist and Shout,” and then really taking flight upon my purchase of 1973’s 3+3 album. It was October 28, 1989, an unseasonably warm autumnafternoon in Chicago; I walked with my friend and bandmate Jason down Ashland from Wilson to Belmont, where the Rose Records outlet was having a big sale. I eyed a copy of 3+3 in the bin, drawn more to the Brothers’ vines than to the track listing, and was about to put it back when Jason intervened.

“You should definitely buy that album,” he told me. “The guitar playing on it is incredible!”

And right he was. Later that afternoon, with the autumn sunlight streaming through our living room windows and certain herbal remedies filling our lungs, we put on my new copy of 3+3 and marveled wide-eyed at Ernie Isley’s sweetly soaring leads and distorted-yet-seductively slinky guitar tone. “What kind of pedal is he using to get that sound?” I asked Jason, but Jason didn’t know. None of the guitar geeks I asked over the years seemed to know, either; sure, some of them had their theories and suggestions, but they never seemed to lead anywhere close to the sonic realms that Ernie — now ranking high among my all-time favorite guitarists — was traversing.

So when I began working on the Stompbox book project, nearly 30 years after that fateful 3+3 afternoon, I knew it was time for me to track Ernie down and learn his “family secret” once and for all. Thankfully, without big brother Ronald there to butt in, Ernie turned out to be quite friendly and forthcoming — and he had some really interesting things to say about more than just his gear…

Thanks for taking the time to do this, Ernie. So, for this Stompbox project, we are focusing on pedals used by iconic players on their iconic records. Which leads me to the million-dollar question: What were you using on “That Lady”?

At the time, I was using a Big Muff fuzz pedal, a phase shifter by Maestro, and I did have a wah — but I didn’t use the wah for the record.

How did you come up with that Big Muff-Maestro combination?

We were in LA at the time, recording what was going to be 3+3, and we had already done the basic track for “That Lady”. It was danceable, it was funky, it was good. And we were going to do the session to put the lead guitar on it, so I went down to the Guitar Center on Sunset. It was just me by myself, and I asked for a Strat, a Muff, and I’d heard about this pedal, the phase shifter. They let me have it, and I plugged in, and I actually discovered the sound in the store. But nobody turned around; nobody walked over to me and asked me any questions. There’s two guitars on “That Lady,” so I played the rhythm guitar part, and then I played the lead guitar part with this new sound that I’d discovered with the phase shifter.

So when I came to the studio that night, I was quite excited. We had our budget up for the recording, and I said, “I’m gonna need an extra hundred.” “Why?” “This pedal that I found.” [laughs] And the engineers were like, “Ernie, whatever pedal it is, we can get it from SIR, Studio Instrument Rentals.” I told them what it was, and the very next day it was there.

We set it up, and I put on the headphones, and when I hit the very first lead note, the entire song changed — and all of us knew it. It was like it went from black and white to 3-D Technicolor. All of us knew it! And it was unlike anything, up to that point, that any of us had collectively heard anybody sound like on the guitar. And the most unusual thing about it was that it was actually me! [laughs]

I played all over the place, and when I’d finished and they played it back, it was like a guitar instrumental. I totally lost it, the engineers lost it, and everybody else was kind of comatose. [laughs] My eldest brother, Kelly, was staring at me through the glass — like, he didn’t blink for 45 minutes!

They said, “Ernie, you’ve gotta do another take, because we’ve gotta make room for the vocals.” I was like, “Vocals? Are you guys crazy? Put it out like that and it’ll be a hit!” So emotionally, I was really ticked.

Because your first take was so magical?

Yeah. So I did a second take, and to make a long story short, the second take is on the record. The first take was better, but that was erased at the time. It was wonderful; it was new, it was a total sense of discovery. So I was ticked that I had to do it again.

We came back about two days later, and Ronald or Rudolph said, “Put up ‘That Lady’!” And I was like, “Oh, my god, I don’t know what I’m going to hear.” Because at the time, I was like, “Erase it — that ain’t no good!” But when they played it back, I said, “Oh, I’m so glad you guys didn’t erase it.” Because that’s the take that went on the record.

When we played the finished album for CBS, Clive Davis — who was still president at the time, but about to be fired, we didn’t know — he said, “Can you guys do ‘That Lady’ as the first single, but make an edit and repeat the singing verse at the end?” So we did it, and that was going to be the single. But when CBS first heard it, they were like, “It doesn’t sound like ‘It’s Your Thing’ — it doesn’t have trumpets and saxophones — but we like it! It’s got an unusual combination of elements. You’ve got the dance thing, you’ve got R&B, you’ve got some funk in there, but you’ve really got this lead guitar thing going on. Wow, that’s really quite a dynamic thing happening with this record! I wonder how we should promote it?”

And we were like, “Man, just put it out. Never mind the categorization; just let it go everywhere.” And when it came out, it went everywhere. Anybody that heard it, they were like, “Have you heard the new Isleys?” “No.” “You haven’t heard ‘That Lady’?” “That’s them?!?” [laughs]

CBS was like, “The guitar tone’s great. Who’s that playing?” “That’s our brother, Ernie.” “Get outta here! There’s more brothers than you three?” “Yeah — we’ve got Ernie on guitar, our brother Marvin on bass, and our brother-in-law Chris Jasper on keyboards.” And that was how we hooked it into 3+3; when the record came out, and it was six people instead of three, and it had “That Lady,” “Listen to the Music,” “Summer Breeze”… it opened a bunch of doors for us. And whatever doors it didn’t open, it kicked them off the hinges.

So, just to clarify — this Maestro phase shifter was the PS-1A, the one with the different colored knobs?

At the time, yes it was, yes.

Did you use it on the rest of the album?

Um, I think I only used it on that song. And I think I wanted it that way. Because the way we had initially assembled the record, “That Lady” was not the first song that you heard. But when 3+3 came out, “That Lady” was the first song that you heard, the lead song on Side One, and it was like, “Who is that?”

I remember that was in my senior year of college, and I had a philosophy class. I came into class, probably in like the middle of September, and there was a guy who sat next to me. He asked me about the notes in class — you know, Socrates and Plato, the best way to live in a society, and all that stuff — and I started going through my notes. And then the next question he asked me was, “Is that you on that record? That sound, oh my god! It’s unlike anybody out there.” [laughs]

And I remember when it first came out, Ronald told me that there were rumors that it was a former houseguest and employee of the Isley Brothers playing on the record. And I was like, Wow, it must be pretty good for them to go there! “Is that Jimi?” “Uh, no, that’s some guy named Ernie.” [laughs]

That whole record was an adventure and a discovery. Throughout our career, we always chased the music; we leave the category thing for other people to concern themselves with. When you look at our resume, you say, “You mean, the same guys that did ‘Twist and Shout’ before The Beatles also did ‘It’s Your Thing’? And then they did ‘That Lady’? How is that possible?” But we were just chasing the music, and we would change with it; we were always willing to change with it.

The 3+3 album really does seem like a defining moment in the Isleys’ career.

Yeah. Because at that time, 1972-73, I could talk about Carlos Santana, I can talk about War; I can talk about the Ohio Players. There were all of these groups that were like bands, you know?

You mean, guys who could really play together?

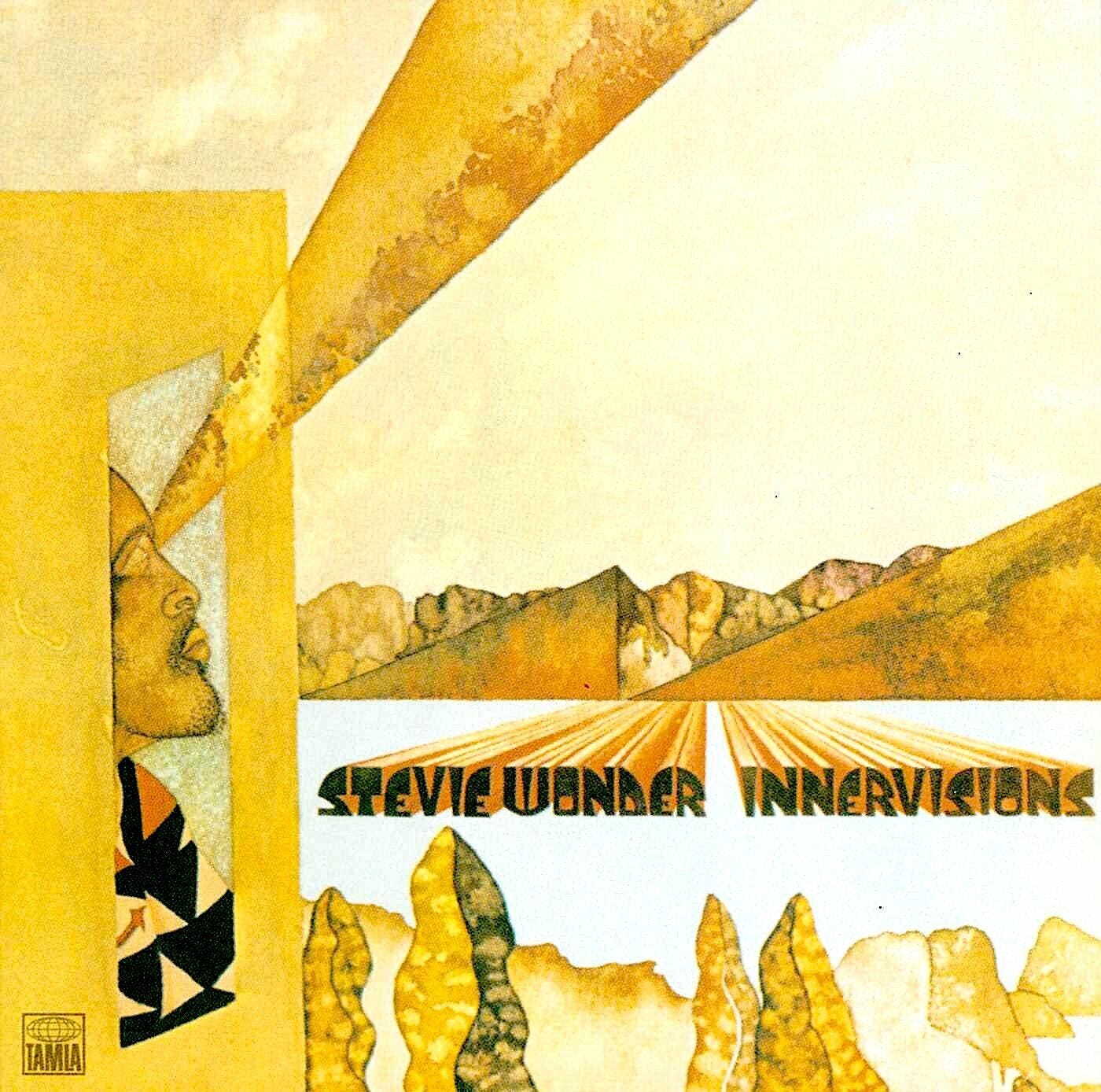

Yeah! And I used to like it, because I could hear the difference in the way the drums sounded with the Ohio Players, as supposed to the way the drums sounded with Chicago. And all of these bands, the music was really quite dynamic. I remember Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Talking Book, Innervisions…

We were working on 3+3 when Stevie Wonder was working on Innervisions, in the same studio [The Record Plant] with the same engineers [Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff]. When they realized how dynamic the two records were going to be, one of ‘em would be at the board, and the other one would be on the couch. And then they would switch, you know?

When the Isleys would come in, they would switch, and when we were finished Stevie would come back in behind us, and he’d be recording, too. So it was quite a dynamic, inspired time. We were just really happy with the final result, especially since it was the first record we were taking to CBS representing the Isley Brothers.

3+3 was also the first album where you got equal billing, but you’d played on some previous Isleys records, like 1972’s Brother Brother Brother LP.

Yeah, I played on “Work to Do,” on “Love the One You’re With” — I was playing 12-string on that. You know, our sound too at the time was kind of different, because of the musical makeup we were applying. I mean, “Work to Do,” it had an acoustic sound; it had an acoustic piano and acoustic guitars, and when you’d turn it up it sounded good, but it just sounded different. It had electric bass, but it wasn’t really “electric”. Our records sounded different. So when we got to 3+3 and “That Lady,” it was like, “Is that them? That doesn’t sound like ‘Work to Do’ or ‘It’s Your Thing’ at all! But we like it!” And that’s more or less how CBS felt.

Did you use the Maestro on subsequent recordings?

I used it on “Live It Up,” and I used it on “Midnight Sky”.

What about on “Voyage to Atlantis”?

That was a Leslie; that was me playing through a Leslie speaker. I was gonna go for a sound [with the Maestro], but when I discovered what I sounded like playing lead through a Leslie, it was like, “Yeah, let me do that!” And that song was different than anything that we’d done.

Back to Jimi Hendrix for a second — did you pick up anything from him, guitar-wise, when he was playing with your brothers and living at your family’s house in the early ’60s?

Well, I will say this: When somebody’s in your house for two years… you can treat two years in terms of a conversation. You can treat it like two minutes, or even twenty minutes. But I was eleven years old when I met him, and Marvin was ten; this was like, March of 1963. JFK is in the White House. If Jimi’s in the house, whenever he’s in the house, at some point he’s gonna be playing guitar. So if you put that into real time, like the course of a day or over a week, or over a month, you get to hear someone that is unlike anybody, speaking personally, that I’d ever seen or heard playing guitar [laughs]… My brothers got him his first Fender.

Wow, really?

Mmm-hmm. And for some people, that’s a surprise. But Fender’s a corporation; they’re not giving stuff away. [laughs] After he was hired, and he didn’t have a place to stay — because he was in New York, and we were in New Jersey — it was like, “You can come and stay at our mother’s house; we’ve got a spare bedroom, and you can meet and rehearse with the other guys in the band.”

And my brothers were like, “Jimi, you play very well, but the guitar you have is kind of scruffy looking. If you’re gonna be with us, we’ve gotta get you a new axe.” And he’s like, “Huh? Really?” “Yeah. What kind do you want?” And he said, “Can I have a Fender Strat?” And Kelly’s like, “Okay!” And Jimi’s like, “Oh my god!”

So, before he came to our home for the first time, they stopped by Manny’s Music in New York, and got him a brand new guitar, a white one. So his mind is totally blown, because nobody’s ever done something like that for him. And I could see him, and hear him, playing that white guitar upside-down virtually every day he was in the house.

That’s incredible. Talk about an education!

God moves in mysterious ways, man. Me and Marvin were not musicians. And when The Beatles were on Ed Sullivan in February of 1964, I hadn’t yet turned twelve. But on the couch was me on the left, Marvin on the right, and Jimi Hendrix in the middle. Ed Sullivan said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, The Beatles!” There was no clap of thunder above our house, and no crystal ball; nobody can see the future. And The Beatles, of course, were thoroughly legit — that was not hype, at all! [laughs]

A couple of days went by after that, and there was a meeting with the brothers. My eldest brother Kelly took the floor, and he said, “This English band, they’ve changed everything. I don’t know what’s going to happen now, even for Elvis Presley himself. But I think we’re gonna be all right, because they play ‘Twist and Shout’ in their repertoire.” And then Kelly said, “They’ve got two guitar players… but we’ve got Jimi!” When he said that, I looked over at Jimi, and he had the biggest grin on his face. [laughs] This is before he was a legend and an icon, with all the history and hype. It was like, “That’s John Lennon, and that’s George Harrison. But we’ve got Jimi, and we’re the Isley Brothers!”

And of course, if he’d still been around when “That Lady” came out, he’d have probably given me something between a bear hug and a tackle. “How the hell did you ever learn how to do that?” [laughs] He would know precisely. “That’s Ernie playing guitar? Well, Ernie never touched my guitar. Ernie didn’t ask me any questions.”

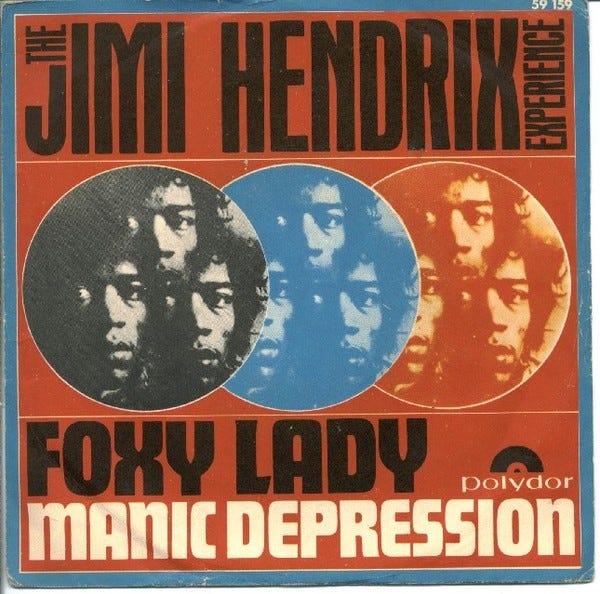

Marvin did — Marvin was all like, “Jimi, how do you know to change strings when you’re looking for a note?” And he’d stop in the middle of practice, or whatever he was doing, and explain. But I didn’t have to hear the Are You Experienced? album to know that he could play, although Ronald did get the record when it came out. And I’d heard all this talk about this song “Purple Haze,” but when I heard the second song, which turned out to be “Manic Depression,” I said, “That sounds like him — that’s the way he plays.” And nobody else played as musically ferocious like him, and with the emotion.

So if he was around, he would know. He would tell you, “The reason Ernie plays that way is because he was always somewhere near, when I was playing in the living room or the dining room.” You know, I wasn’t really studying social studies; I was listening and absorbing and observing…

When was the last time you saw Jimi?

After around November of ’65, I didn’t see him anymore. “Kelly, where’s Jimi?” “Oh, Ernie, we had a talk, and he said how much he appreciated the hospitality, and all of that, but he wants to do some other things. So we parted on good terms, but he did ask for one favor before he left.” I said, “What’s that?” “He wanted to take the white guitar with him!” [laughs]

A parting gift?

Yes! So we gave it to him. In June 1969, we had a concert at Yankee Stadium, and Kelly reached out to him. “Jimi, we want you to do the Yankee Stadium concert with us!” Jimi was like, “Oh yeah, man, I’d love to do it, but let me talk to my people and get back to you.” A couple of days went by, and then he told Kelly, “I’d love to do it, but I’ve got a commitment to something called the Woodstock Arts and Music Festival; it’s gonna be in upstate New York, at a farm somewhere or something. The promoters are concerned that if I do Yankee Stadium, I might hurt ticket sales.” Yeah, right — he obviously didn’t have a crystal ball, either! [laughs]

So basically, Jimi’s influence on your playing was really more of an osmosis thing?

Yes. Jimi would have known why I played like that, but he wouldn’t have seen it coming — none of us did. Because Marvin and I weren’t musicians at the time. And my first instrument was drums! [laughs] I didn’t even pick up a guitar until 1968…

You would have been, what, sixteen at the time?

Yeah, I was sixteen. I started on drums, first, and at fourteen I played my first live gig, in Philly with the Isley Brothers and Martha & the Vandellas. Martha & the Vandellas didn’t have a drummer, so I played with them the same night. [laughs]

That’s a nice way to break into the business!

Oh, man! You know, after we performed — Ronald had introduced me, “Our little brother back here on drums, Ernie!” — I came offstage, and Kelly handed me a fifty-dollar bill, and told me to go out and get a hot dog! [laughs] My mind was totally blown. So I come out of backstage, still in my stage clothes, and there’s about 12 or 16 girls, all my age, and they screamed at me like I was Justin Bieber. I was like, “Man, I need to move to Philly!” [laughs]

It was my baptism, my introduction to what it was like to play onstage. It was fun — and at fourteen, it’s thoroughly fun! And when you’ve got all these girls going, “Do you go to school down here? Give me your phone number!” Aw fuck, man! “I’ve gotta go home tonight. I wish I could stay down here for a couple of weeks, but I can’t.” It was fun. It was a growing experience, a learning experience, a sense of discovery. And it was like that with the record of 3+3 and “That Lady”. Because none of us knew that song was going to change right in front of us.

I know your brothers had previously recorded a version of it in the mid-’60s…

Yeah, around ’64.

Which was a great recording, too, but it obviously had a much different feel going on.

Right — cha-cha and bossa nova.

But the 1973 version sounded so futuristic. I remember hearing it in the car as a kid — I had no idea who you guys were, but I thought it sounded like you were on a spaceship.

Nothing out at the time sounded like it. There was an edited version for AM radio, but when the album came out, it was like, “Man, that’s some dynamic stuff!” And of course, there was all kinds of stuff like that that came after it. But at that time, it changed how we were thought of.

Do you still have that Maestro pedal?

If I do, it’s in a box somewhere. But like anything else, it’s a stepping stone along the way for the journey that you’re on. You don’t linger; music doesn’t stay the same — it goes on. Like, “Shout” is part of the opening of rock and roll, Dick Clark and American Bandstand and all that. And then, “Twist and Shout” is in the twist era, and “This Old Heart of Mine” is Motown. So the music keeps moving; it keeps you going forward. And that was one of the things about the English Invasion — when that showed up, it wasn’t gonna go back to Fabian and Paul Anka. That was still there, but it was like, “Something else has happened this Sunday night, because of Ed Sullivan. What happened, we don’t know yet. But something has changed!” [laughs]

What do you use to get the “That Lady” sound onstage these days?

Uh, I’ve got some pedals by Boss; I’ve got a Rat pedal, a fuzz box which sounds similar to the Big Muff, and I’ve got a wah. But with all due respect to the toys that somebody might have on the floor, the X-factor ingredient is the player. We recently did a record with Carlos Santana, and I’m grinning ear to ear as he’s playing, and then he points at me and I start playing, and I look up and he’s grinning. Carlos sounds like Carlos, and Ernie sounds like Ernie — and isn’t that great? The player themselves is ultimately going to make the real difference, regardless of amplifier or the stuff you may have on the floor.

I love how in your tellings of significant musical discovery Jason is frequently the Buddha and you are Ananda.

Fantastic, I did not know that story, so glad you got him to tell it!