(…or, How The Bee Gees Helped Me Win A Starting Spot In My Little League Lineup)

Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers!

Some thanks are in order before we get into today’s post. First of all, thank you to everyone who enjoyed, shared and engaged with my Aerosmith tribute post from earlier this week — it’s turning out to be one of the most popular things I’ve written for JTL, and I’ve been enjoying the hell out of the resulting comment thread.

Also, thank you (and welcome!) to all the new folks who have subscribed to JTL this past week, as well as those of you whom have recently upgraded your free JTL subscriptions to paid ones. Said upgrades have really helped me get “over the hump” as my bank investigates the fraudulent charges that drained my checking account while I was away in Scotland, and I am immensely appreciative of and grateful for your support, as I am for everyone who has contributed some of their hard-earned cash to help keep this thang cookin’ over the past two years.

As I mentioned back when I launched Jagged Time Lapse, one of my original intentions with this Substack was to motivate me to get cracking on my musical-memoir-in-progress — and to share bits of it with my paid subscribers, whenever I have a new chapter that feels ready for an audience.

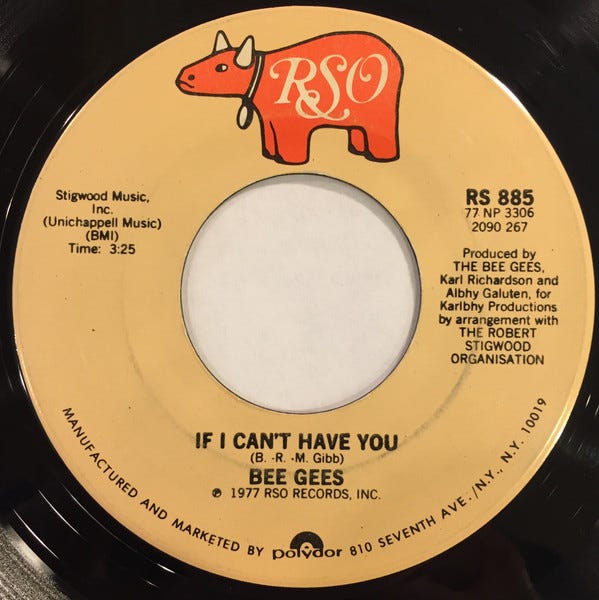

I don’t yet have a working title for the book, but the concept is similar to what my friend and colleague Josh Wilker did with his wonderful Cardboard Gods. Except where Josh used baseball cards from the 1970s as a means to make sense of his past, I’m using 45 rpm singles as a series of windows into my turbulent adolescence — a period of my life which coincided with some of the greatest music ever heard on AM (and FM) radio, as well as some of the absolute worst.

All the previous chapters I’ve completed for the book — like the one about why Nigel Olsson’s “Dancing Shoes” makes me think of Mormons and Chief Dan George, or the one about or the one about how the film Grease mirrored my hellish entry to junior high, or the one about how R.E.M. eased my transition from high school to adulthood — can be found in the Jagged Time Lapse archive, which also contains a ton of free reads on a wide variety of music-related subjects. If that sounds like your kind of jam, five bucks a month or fifty bucks a year for a paid JTL subscription will get you all the Dan Epstein writing you can handle…

It’s strange but completely true: In the spring of 1978, a Bee Gees B-side helped me win a spot in the starting lineup of my little league baseball team.

If that seems improbable now, looking back from a distance of over 45 years, it would have been absolutely impossible for me to imagine a year before it actually happened. For one thing, I had no idea in 1977 who The Bee Gees were, despite having heard their hit “You Should Be Dancing” at least a hundred times on the radio in the summer of 1976. For another, my 1977 little league debut had been an unqualified disaster.

Having fallen head over heels in love with baseball the year before — thanks to a season that I eventually paid loving tribute to in my book Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ‘76 — and having spent the ensuing winter reading everything about the game and its history that I could get my hands on, I resolved to play ball for Burns Park’s little league team come the spring of ‘77… as a catcher.

This resolution was deeply flawed from the get-go, not to mention arguably insane. Catchers are generally big, strong dudes, and I was easily the smallest and weakest kid on our fifth grade team. Catchers are also supposed to, well, catch the ball whenever it’s thrown to them, and I had far from mastered the art of closing my glove (catcher’s mitt or otherwise) quickly enough to keep the ball from popping out of it.

But I knew from my reading that the catcher was essentially the “captain” on the field; I figured that, between the intensive baseball knowledge I’d absorbed in the off-season and my classroom popularity, I was naturally qualified for the position. Plus, I loved Thurman Munson (who decades later would become the subject of my third baseball book) and Johnny Bench, and catcher’s gear looked really cool to me.

Alas, my catching dreams lasted for only a couple of agonizingly embarrassing team practices, ending for good when I took a fastball off my forehead while warming up a pitcher on the sidelines — an assignment our asshole coach had given me despite fact that the team only owned one catcher’s mask, which our actual starting catcher Andy was using at the time. Thereafter, I was assigned to the position where an inept little leaguer can do the least amount of damage to the team or himself: Right field.

All of which would have been slightly less soul-crushing if I’d been able to make up for it with my bat, but I was just as hopeless at the plate as I was in the field. I think I made contact exactly once that season, miraculously knocking a long fly ball foul of the third base line before eventually striking out for the umpteenth time. The only time I ever got on base was via getting hit by a pitch, or drawing a walk — but my ability to accurately gauge the strike zone was so poor that the latter event rarely happened.

Our whole team was pretty awful in 1977, but I was easily our worst player. And I discovered that popularity in the classroom doesn’t necessarily translate onto the field, at least not when you totally suck — “Easy-Out Epstein” really wasn’t the sort of baseball nickname I’d envisioned for myself. But despite the constant humiliation, I simply loved the game too much to give it up. One way or another, I would be back on the diamond in 1978.