Music documentaries — or rockumentaries, if you will — are problematic by nature. It’s really difficult to do full justice to an artist’s career in just an hour or two; and even if a film utilizes amazing vintage footage and insightful interview subjects, hardcore fans will often still complain that the documentary didn’t go deep enough, or grouse that some favorite part of the artist’s story didn’t make the cut.

I have seen (and also been involved in) enough music docs over the years to keep my expectations low whenever I watch a new one. For every total gem out there like The Turtles: Happy Together (a shot-on-a-shoestring 1991 doc that nevertheless perfectly and hilariously captures the spirit and history of that woefully underrated band), there are at least a dozen music docs that are at best forgettable and at worst infuriating. And I have definitely watched (or at least tried to watch) some pretty infuriating ones; as I wrote a year and a half ago after watching Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd:

These time-wasting barrel-scrapers are generally identifiable right off the bat: No one from the band or its immediate circle is actually in the doc; none of the artist’s music is included, because the filmmakers couldn’t afford the clearances; and the same photographs are used over and over again, because the filmmakers couldn’t afford to pay for footage or photo clearances, either. I often get suckered into watching them because the topic is a compelling one, then wind up hitting the “Off” button on my remote in frustration within ten minutes.

However, if a doc turns me on to great music that I was previously unfamiliar with — or sends me back to re-immerse myself in music that I’ve taken for granted for too long — then I ultimately have to view it as a success, regardless of its faults. Which is how I feel about Boom: A Film About The Sonics, the 2018 documentary by Jordan Albertsen that has recently become available on numerous streaming platforms. On the one hand, the documentary had me repeatedly pounding my forehead against my desk over one missed opportunity after another; on the other, it also reignited my love for a band that I was absolutely obsessed with back in the 1980s, but whose wax I hadn’t cranked up in far too long.

Arguably the greatest garage band of the 1960s — and, by extension, of all time — The Sonics were a quintet from Tacoma, Washington whose strait-laced appearance belied their blistering sound and almost unhinged intensity. Though they never found much commercial success outside of the Pacific Northwest (where their 1964 debut single “The Witch” sold well enough to top the charts of Seattle’s KJR, but was artificially kept at #2 because the station deemed it “too far out” to be #1), the impact and influence of their music has been vast and mighty. They’re a band totally deserving of a documentary, and super Sonics fan Albertsen has obviously put his heart and soul — not to mention many years of his life — into making this one happen.

And for its first thirty minutes or so, I found Boom incredibly exciting and engaging. Not only did Albertsen get all five members of the band’s classic lineup — guitarist Larry Parypa, his bassist brother Andy, drummer Bob Bennett, sax player Rob Lind, and lead screamer/organ player Gerry Roslie — in front of the cameras to tell their story, but he also wisely included Buck Ormsby as a major character in the film. Ormsby, the bassist of local legends The Wailers, signed The Sonics to his record label Etiquette and oversaw the release of their first two albums (1965’s Here Are The Sonics and 1966’s Boom) as well as their first seven singles. He was a hugely important figure in the PNW music scene of the 1960s, and Etiquette quite rightly remains a revered imprint among fans of sixties stomp, so it’s great to see them both getting their cinematic due along with the band.

While sadly no footage seems to exist of The Sonics in action (at least not during their 1960s heyday), Albertsen does a wonderful job of recreating the excitement of the band’s early days via a combination of rare band photographs, vintage films of Tacoma and Seattle, and the members’ vivid and occasionally hilarious recollections. He also nicely connects the dots between The Sonics’ recorded legacy and the music of later PNW bands like Heart, The Fastbacks, Mudhoney and Soundgarden, some of whose members ardently testify onscreen to the band’s enduring magic.

What he doesn’t do, however, is dig much at all into the actual music, at least beyond the recording of “The Witch” and its raving b-side “Psycho,” the band’s first two original tracks. Other than the band’s early idolizing of The Wailers, Roslie’s quick rundown of his early influences (Elvis, Little Richard) and his brief admission that he was “always into spooky stuff,” we get no sense at all of what inspired them to make music — the Dave Clark Five were obvious full-bore forebears, but they’re never mentioned — or to write such badass horror-themed rockers as “Strychnine” or “He’s Waitin’,” the latter of which invoked Satan by name a good two decades before Slayer’s Hell Awaits. In fact, of the ten Sonics tracks that are heard in the film, only four are even mentioned by name, and only two are discussed at all by the band members themselves.

Here Are The Sonics and Boom are crucial cornerstones of the American garage rock discography; both albums are filled with classic originals and blistering covers, but the documentary gives us precious little insight into their actual creation. The band’s third album, 1967’s confusingly titled Introducing The Sonics, is brushed off with Albertsen’s brief comment that “the record was considered a massive critical and commercial failure.” Though that album was recorded for Jerden Records, another hugely important PNW label of the era, nothing is mentioned about Jerden’s history or why the band would have chosen to jump to that label after becoming dissatisfied with Etiquette. And then, the band breaks up — only 34 minutes into the documentary.

Albertsen could have easily left himself plenty of time to explore the band’s uniquely powerful music and the members’ recollections of making and performing it. Instead, less than halfway through the film, he drops that thread to explore the band’s “mysterious” posthumous popularity in England and Europe. He flies to London and traces the trans-Atlantic awareness of the band to the inclusion of “Psycho” on Big Beat’s 1984 compilation Rockabilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease, apparently oblivious to the fact that bands like The Syndicate of Sound, Don & The Goodtimes, The Swamp Rats, The Droogs, DMZ, The Cramps, The Pointed Sticks, 8-Eyed Spy, The Nomads and The Chesterfield Kings — most of whom would have already been very familiar to European garage heads (hell, The Nomads were from Sweden!) — had all recorded covers of Sonics material before 1984. [Also, as a Facebook friend of mine pointed out this morning, the entire third Sonics album was actually reissued in Spain in 1980.] The burning question for me here was not, “OMG how could The Sonics possibly have an overseas fanbase?” but “Did Albertsen not actually have a working internet connection?”

From there, Boom sloppily meanders through the band members’ post-Sonics existence — it is pretty weird to think of the guys behind such deliriously crazed records pursuing livelihoods as car salesmen, commercial pilots, insurance executives and history teachers — the usual “band reunites for a new generation of fans” beats and some belated father-son bonding between Albertsen and his Sonics fan dad. It ends on a bittersweet note, with various members being replaced for the reunion tours due to ill health and Buck Ormsby (who co-produced the film) passing away in 2016 before Boom could be released. (Bob Bennett, who comes off in the doc as particularly likable, sadly passed away just a few weeks ago.) But the film does at least leave you with the sense that the band members came to understand the importance of their legacy, and thankfully lived long enough to receive some global love for it in return.

And, as frustrating as I found the documentary’s flaws and its pronounced loss of energy and focus after the first half-hour, the band members’ diverse personalities do come across in a most endearing way, and The Sonics’ needle-pinning attack practically bursts through the screen during the film’s early portions. So if Boom isn’t quite the cinematic tribute the band deserved — which is of course frustrating, because there most likely won’t be another — it’s still entirely capable of inspiring previously unfamiliar listeners to go out and grab some Sonics records (or at least stream them on Spotify). Which can only be a good thing.

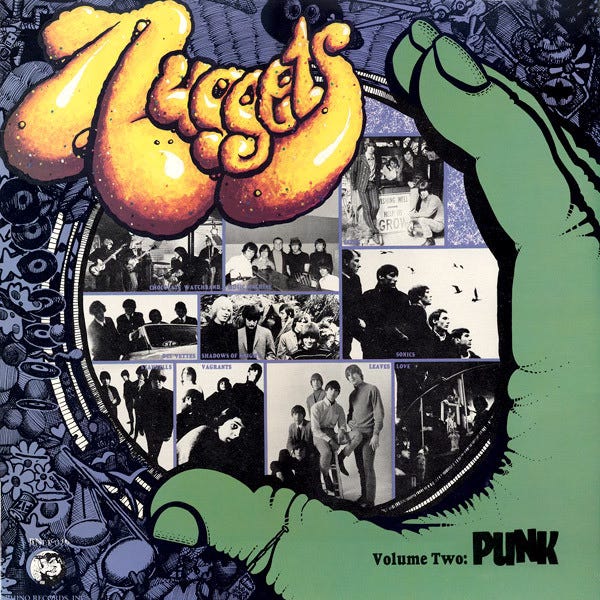

The film certainly brought back memories of my own introduction to The Sonics, which happened in 1984 not via Rockabilly Psychosis but rather Rhino Records’ compilation from the same year titled Nuggets Volume Two: Punk. Even on an album packed with such snot-encrusted fuzz-busters as The Music Machine’s “Double Yellow Line,” The Del-Vetts’ “Last Time Around,” and The Shadows of Knight’s “I’m Gonna Make You Mine,” The Sonics’ “Strychnine” stood out for me with its evil four-chord lurch and Larry Parypa’s burning guitar solo. Throw in their moody cover pic and Harold Bronson’s liner-note mention of Gerry Roslie as “The White Little Richard,” and I immediately knew that I needed to hear more of this band.

Of course, living as I was in the mid-eighties Midwest, my gratification was far from immediate. It wouldn’t be until the fall of 1985 that I stumbled across a 1977 reissue of Introducing The Sonics — retitled Original Northwest Punk — in a used record store in (of all places) Washington, DC’s Georgetown neighborhood, which I was exploring while visiting my dad during October break from my freshman year of college. I recognized the titles “The Witch” and “Psycho” from the Nuggets liner notes, and immediately snapped the album up for the princely sum of five bucks.

Introducing The Sonics may have been “considered a massive critical and commercial failure,” as Albertsen alleges — though he offers no sources to back this up — but I thought the album was pretty damn mind-bending when I got back to school and slapped it down on my roommate’s turntable. If “The Witch” and “Psycho” (included here in the same versions recorded for Etiquette two years earlier, surely an indication that the band’s creative well was beginning to run dry) were the obvious highlights, I dug most of the other tracks on there, especially “Like No Other Man,” “You Got Your Head On Backwards” and their organ-stoked version of Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man”.

But the first two Sonics albums, as I discovered about another year after that, were indeed even better; between them and the various stray tracks I found on other compilations (like “Don’t Believe in Christmas,” their ripping holiday rewrite of Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business”), I don’t think I hosted a single installment of my weekly college radio show that didn’t feature a Sonics song.

Aside from Roslie’s inimitable howl, what always set The Sonics apart from most of their American garage contemporaries for me was that they didn’t try to ape their British counterparts. Their keys-and-sax-driven lineup was certainly similar to that of The Dave Clark Five (whose cover of The Contours’ “Do You Love Me” was in turn covered on Here Are The Sonics), and they did record a cover of British pop star Adam Faith’s “It’s Alright,” but their look, sound and G-force energy was completely their own.

I’ll never forget the first time I heard The Sonics’ cover of Richard Berry’s “Louie Louie” — the boozy, good-time sway of countless other renditions was totally absent, replaced by the full-frontal assault of a band that was clearly out for blood, and I had to peel myself off the wall when it was finished. Listening back to it again now, two days after I watched Boom: A Film About The Sonics, it still stands as the greatest version I’ve ever heard, by far. And some sixty years on, the band’s original recordings sound even better than ever.

I haven't seen the Sonics doc yet, but my favorite is probably MC5's A True Testimonial, which was pulled (I believe by Wayne) before it was officially released. However, before it was pulled, DVD copies were sent in advance to various labels and magazines for review and a buddy of mine who worked for Charley Records in the UK was sent one. Knowing I was a big fan of the 5, he gave it to me after he wrote his review! The copy also has a ton of outtakes, which makes it quite unique and rare.

Surprisingly, I also really liked the Bee Gees doc, which I found fascinating, yet sad.

"However, if a doc turns me on to great music that I was previously unfamiliar with — or sends me back to re-immerse myself in music that I’ve taken for granted for too long — then I ultimately have to view it as a success, regardless of its faults" - Absolutely