Ian Hunter: "I much more enjoy the 'hovering in the dusk' kind of thing."

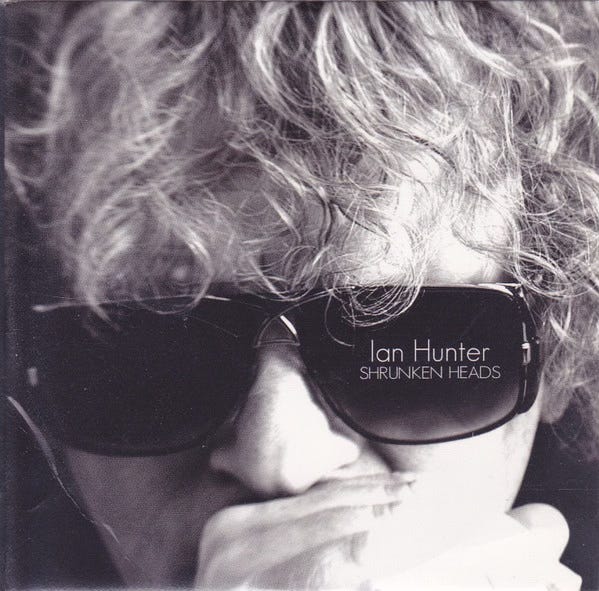

Talking about Shrunken Heads, Mott's glory days, the “Bowie bubble” and the pitfalls of fame with the man behind the shades

In April 2007, my editor at the now-defunct Guitar World Acoustic magazine assigned me to interview Ian Hunter about his forthcoming album Shrunken Heads, an assignment I accepted with equal degrees of excitement and trepidation.

I’d been a massive Ian Hunter fan since about 1980 or so, when I fell in love with “Cleveland Rocks,” “We Gotta Get Out of Here,” “Just Another Night” and other WLUP-spun Hunter solo tracks well before putting it together that he’d also been the frontman of glam-era greats Mott the Hoople. And while interviewing a veteran rocker about his latest work can at times be a less than appetizing prospect, the new album, co-produced with longtime collaborator Andy York and featuring the stellar but sympathetic backing of James Mastro (The Bongos), Graham Maby (Joe Jackson Band) and former Wings drummer Steve Holley among others, turned out to be a genuinely great record. Hunter, who would turn 68 that June, showed no sign of losing his gifts as a songwriter or vocalist, and songs like “Words (Big Mouth,” “Soul of America,” “When the World Was Round,” “Brainwashed” and the title track showed that his observational wit had only sharpened with age.

Still, the impression I’d gained of Hunter from reading various interviews over the years — along with his grimly hilarious Mott tour memoir Diary of a Rock n’ Roll Star — was of a highly intelligent person who didn’t suffer fools gladly, and I was filled with anxiety about the possibility of somehow “putting my foot in it” with one of my all-time favorite songwriters.

Thankfully, I needn’t have worried. The Ian Hunter that I got on the phone that day may have been predictably gruff, but he was also extremely funny and self-effacing, not to mention surprisingly chatty. “Well, that was painless,” he said to me at the end of our call. Coming from him, that felt like a high compliment, indeed.

While I have always remembered this interview fondly, I only recently rediscovered the audio file of it hidden away in an external hard drive. Most of what ended up in the magazine from our chat pertained to Shrunken Heads and the guitars he’d used to record it, but we also talked that day bout his early songwriting efforts with Mott, the glam millstone that’s been hanging around his neck since about 1972, the brilliance of Sonny Bono, and Mott’s influence on the original UK punk scene. None of that has ever run anywhere else, but it’s all here now as a special for my paid subscribers.

And if you’re not a paid subscriber, just $5 a month (or $4.17/mo if you opt for the annual subscription option) will get you access to all of the exclusive interviews like this one in the JTL Vault, along with the completed chapters of my adolescent musical memoir-in-progress — like this one about discovering marijuana and Foghat Live on the same bus ride, or my ill-fated first “band practice” — and all the full episodes of CROSSED CHANNELS, the monthly music podcast I do with my friend and fellow scribe Tony Fletcher. Our 21st episode, this one on the subject of Northern Soul, is now up here:

I think that’s a pretty solid value for just the price of one large coffee drink or pint of beer per month — and if you do too, and would like to support good independent music writing in this dire media landscape, please click the button below and head to the “paid subscription” option. A thousand thanks to all of you who have already done so; you quite literally keep the lights on over here.

(And FYI: if you already have a paid JTL subscription but find that you can now no longer access my “paid-only” posts, please check to see if the credit card you have on file needs to be updated.)

And now, on to our scheduled program…

Shrunken Heads feels like a perfectly-formed album to me — but according to the press release, it all came together rather quickly.

Yeah, well, I’ve been working with the guys in the band in different sort of formations for the last seven years, so we got used to each other. They sort of know my melon, and I know theirs, you know; but we did it really quickly. We had a couple of days’ rehearsal in my basement, and then we went into the studio; I think we did 16 tracks in about five days. It was a few overdubs later on, but the meat of the thing was all done in that original blast.

Do you prefer to record that way — to, like, get the basic tracks down in one go?

Well, yeah, the quicker the better. I mean, very often it doesn’t turn out that way. It’s like movies; you go in with the best of intentions… But this time, it was pretty much Andy York and myself. We had guys come in individually, and then we had them together. It was a plan, an economical plan. And it worked great.

I was looking for a window where all the guys that I work with were free, because they all work for different people, you know? And there became a window where they were all doing nothing, and so that we sort of grabbed that for, like, a target to go for. And that was pretty much it. I kind of work well under pressure like that.

How long did it take you to get this batch of songs together?

Oh, I don’t know; I can never really tell. What happens is, usually, you sort of get an album out, and you go on tour, and you lose the muscle — I can’t write on the road. And when you come back, it’s like you’ve never written a song in your life, and it’s like starting all over again. So for a few years you bumble about, and then stuff starts coming through after a while.