Sometimes, when I’m having trouble falling back to sleep after my cat Angus impatiently drums me awake at 4 a.m. to dole out breakfast for him and his brother Hugo, I’ll close my eyes and take a mental stroll through some of the many houses and apartments I’ve lived in over the decades.

One of my favorite places to go back to is the old three-story house on Ann Arbor’s Morton Avenue, which my folks rented from 1969 to 1974. That five-year span was the longest I lived in any domicile until my thirties, so maybe it’s no wonder that I can still call it up in fairly vivid detail. But it was also the site of a lot of happy, formative times for me between the ages of three and eight — none happier or more formative in some ways than the hours I spent on the living room floor drawing pictures, reading MAD magazine and various DC comics (and/or books on the American Revolution, Civil War and both World Wars), while also listening to whatever records the adults in the house happened to be spinning at the time.

Music wasn’t a main interest for me back then — I don’t recall ever asking to hear a specific record — but it wasn’t just background noise, either. I was acutely aware that certain melodies could stir certain emotions in my young soul, even if I had no real ability to articulate what I was feeling or why I was feeling it. And I always listened to the words, paying close attention to the pictures that they painted. Adult-oriented lyrics perked my ears up from very early on, at least once I got past my “Yellow Submarine”/”Puff the Magic Dragon” phase, because I somehow understood that they offered a window into the workings of the grown-up world, a world I was both fascinated with and extremely mystified by.

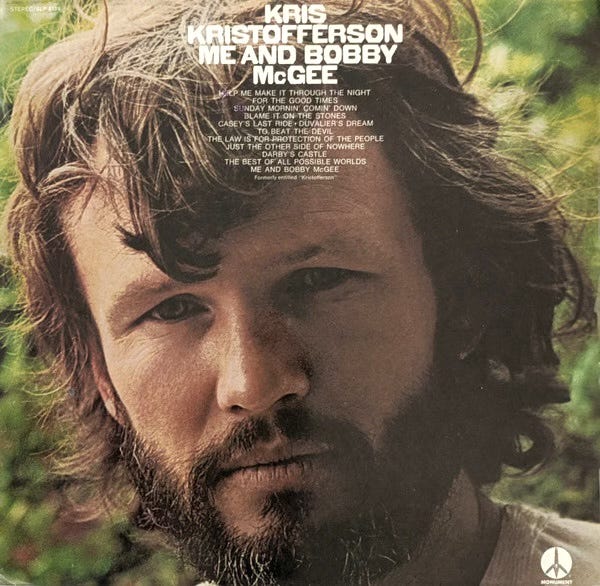

My mom was a huge Kris Kristofferson fan, as were most of her hippie friends, so he was a pretty constant presence in our house. And I use the word “presence” advisedly, because every time someone played his albums Jesus Was a Capricorn, The The Silver Tongued Devil and I, and especially Me and Bobby McGee — the retitled repackaging of his eponymous 1970 debut, re-released in 1971 after Janis Joplin scored a posthumous hit with the title track (and yes, I just committed the rock critic faux pax of using “eponymous” and “posthumous” in the same sentence) — it felt like he was right there in the living room with me.

I never got that same feeling from Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, or the first two Band LPs, Arlo Guthrie’s Alice’s Restaurant, Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water, Carole King’s Tapestry, or the Grateful Dead’s Workingman’s Dead, to name some of the other albums in regular house rotation at the time. But Kristofferson’s records seemed to beam him directly into our house, and I liked listening to the stories he had to tell, even if I didn’t necessarily understand them or the personal travails that inspired their creation. He seemed tired and cranky, but also dryly funny, and most of all real; I could easily imagine him looking over my shoulder at my drawings or my copy of Mad, and offering up a wry but encouraging comment on the subject. Little did I know at the time that he could have also had some insightful things to say about my books on military history.

Unlike many of my music industry pals and colleagues, I never knew or even met Kris Kristofferson, and I can’t say I roll particularly deep with any of his albums past, say, 1974’s Spooky Lady’s Sideshow. But losing him this week still feels like losing a member of my extended family, if only because he was with me in our living room so often between nursery school and second grade that he may as well have been babysitting me and my sister. Though two years younger than me, she responded to his music as well; I vividly remember her referring to “Blame It On The Stones” as “Climb All Over the Stone,” and asking my mom to play it again.

My dear friend Erik Sugg wrote something on Facebook yesterday that really rang true for me, and I don’t think he’ll mind me reprinting it here:

One of the many things I always loved about Kris Kristofferson, in addition to his amazing music and his acting talents, was that he turned the whole notion of “masculinity” upside down... He had grit but he also had vulnerability. He lived a life without fear and otherizing, and he possessed a beautiful openness towards others.

I think that’s largely true. I suspect he did live with some degree of fear, especially during his days as a struggling songwriter, when his family disowned him and his first marriage was falling apart; but if that’s the case, he seems to have turned that terror inward, rather than using it as an excuse to act out or punch down with his songs. But after reading Erik’s words, I found myself wondering if that same combination of grit, vulnerability and a basic sense of fairness — which he famously exhibited while supporting Sinead O’Connor during her controversial appearance at the 1992 Bob Dylan tribute concert — wasn’t something I instinctively sensed from the get-go, and a big part of why his voice and presence felt so welcome and attractive to me in my early youth.

I think about the three most important men in my life — my dad, my Grandpa Fred and my Uncle John — none of whom fully conformed to stereotypical American notions of “masculinity,” but all of whom made me feel safe and appreciated as a child. Kristofferson conveyed the same comforting sense of warmth, intelligence and playfulness that the three of them possessed, and maybe that’s why I always liked having him around.

It also may be why his singing voice always sounded perfectly fine to me. Obviously, the man himself would have told you that he was no Enrico Caruso, nor even a Johnny Cash; but I remember being shocked and confused in my teens when I opened up my copy of Christgau’s Record Guide and read Robert Christgau’s assessment of Kristofferson’s singing on his debut album:

He’s the worst singer I’ve ever heard. It's not that he’s off key — he has no relation to key. He also has no phrasing, no dynamics, no energy, no authority, no dramatic ability, and no control of the top two-thirds of his six-note range.

I mean, that’s a tad wide of the mark, innit? Even coming from the man who once called Jimi Hendrix “a psychedelic Uncle Tom”…

No, Kristofferson wasn’t the most artful or refined singer to ever caress a microphone, but his low-pitched rasp and matter-of-fact delivery was part of what gave his songs their considerable gravitas. Much as I enjoy and admire, say, Al Green’s rendition of “For the Good Times” or Janis’s hit version of “Me and Bobby McGee,” I’ll take Kristofferson’s recordings of these and all his other oft-covered songs over them, because Kristofferson’s songs never sounded as rich, complex or as thoroughly lived-in as when he sang them himself.

Kristofferson lived a long, complex and incredibly rich existence, of course, and this Guardian obit by Adam Sweeting hits the high and low points of it so I don’t have to do so here. I was already well aware of most of what Sweeting mentions — his Rhodes scholarship, his military career, his film career, his alcoholism, his proud left-wing political stance — but one plot point which completely took me by surprise was that, while attending Oxford in the late 1950s, Kristofferson tried to get a singing career going with the assistance of British “beat svengali” Larry Parnes.

A flamboyantly gay impresario, Parnes already had a stable of handsome young pop idols like Billy Fury, Marty Wilde, Tommy Steele, Vince Eager, Duffy Power and Johnny Gentle on his managerial roster, all of whom he had renamed (or so went the popular rumor at the time) to reflect their performance in bed. Dubbing him “Kris Carson” — an alias which doesn’t align particularly with the aforementioned rumor — Parnes secured Kristofferson some recording sessions with legendary producer Tony Hatch, but nothing came of them.

These recordings have never resurfaced, at least to the best of my knowledge, but they were probably ghastly; Kristofferson’s untutored voice worked great in the context of his own songs and the earthy production of his early albums, but I can’t imagine it sounding anything but wrong cosseted in the claustrophobically sweet production styles favored by the British music biz in the pre-Beatles era…

Not that he fared much better when he returned to the UK in 1970 for a gig at the Isle of Wight Festival. To be fair, the festival — as demonstrated in the amazing documentary Message to Love — was already total shitshow by the time he and his band (which included former Lovin’ Spoonful axeman Zal Yanovsky) took the stage; and even if it had been a far less unruly affair, the festival’s flimsy sound system wouldn’t have been much good at conveying the subtleties of Kristofferson’s songs to the gigantic audience.

But I love this clip all the same, and laugh every time Kristofferson — not yet the bearded and confident country-hippie adonis he’d become in just a year’s time — gazes out at the crowd with a mixture of bemusement and “I’ve seen some shit before, but not like this” trepidation, clearly wondering what the hell he’s doing there. “I think they’re gonna shoot us,” he deadpans to his bandmates, before finally bailing out altogether…

Thankfully, this being the UK, no one did shoot them — and Kris Kristofferson went on to live, write, record and act for the bulk of the next half-century and change. As I’m sure is the case with many folks right now, his passing makes me want to go back and explore some of his albums that I missed, as well as rewatch Cisco Pike and some of his other excellent screen performances. But mostly I just want to go back to that living room on Morton Avenue, and hear him singing to me about broken romances, hangovers, Sunday mornings, mysterious women and deeply flawed men while I put the finishing touches on yet another drawing of a WWI dogfight.

Rest in Power, Kris. Thanks for the good times — and for “For the Good Times,” while we’re at it.

That Isle of Wight footage is priceless!

A sweet and mellow homage that brings back memories for me as well of dogfight and civil war drawings and the Peace at Appomattox.

But don’t feel badly about the eponymous/posthumous gaff. The trick is to pair the former with restaurant, and avoid going to the latter. Easy-peasy. 🤷🏽