Love is More Than Words

Flashing back on some run-ins with the late, great, exceedingly complicated Arthur Lee

Yesterday, March 7th, would have been Arthur Lee’s 78th birthday. While deadlines and other obligations kept me from paying tribute to the Love man on the actual date of his birth, I figured there wouldn’t be anything wrong with hailing him a day late. After all, “Love is More Than Words or Better Late Than Never,” as a particularly epic psychedelic track from the 1969 Love album Out Here is titled…

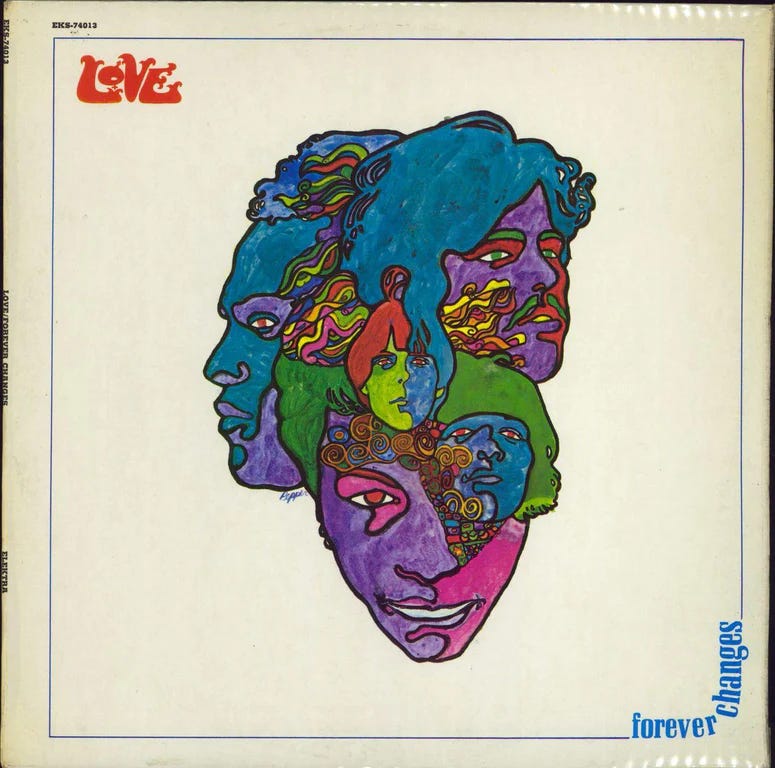

The first Love record I ever owned was 1967’s Forever Changes, which I purchased — on the same fateful October 1986 New York City record shopping excursion that led me to the my first copy of the third Velvets LP — without ever having heard a note of it. I was familiar with their earlier singles “My Little Red Book” and “7 & 7 Is” via oldies radio shows and various compilations, and had dug them mightily, but I’d read that Forever Changes was a whole different ballgame. My knowledge of classic psychedelia was still pretty limited at the time, but my interest (both in the music and the drugs that inspired it) was growing, and the fact that some critics considered Forever Changes THE greatest psych LP of all time meant that I absolutely needed to seek it out.

But when I got my copy back to my dorm room and popped it onto the turntable, I felt initially confused and underwhelmed. From all the raves and descriptions I’d read, I was expecting something along the lines of mind-frying, wall-warping, color-spraying psychedelia — not this hushed, quasi-elegant affair with acoustic guitars and Johnny Mathis-type vocals.

At first, I thought the record must have been overhyped… but then I listened to it a few more times, and then a few more times after that with headphones. And with each spin, the subtle brilliance of the album revealed itself, and the colors (and the striking lyrical images) within gradually came to vivid life. Two months later, I found myself standing at the top of L.A.’s Barnsdall Park singing “Sitting on a hillside/Watching all the people die” and trying to imagine what the city below must have looked like during the smog-choked “Summer of Love” when Forever Changes was written.

Over the next three years, I managed to hunt down all of Love’s albums, as well as Arthur’s post-Love solo work, which was not an easy task in the days before the internet, eBay, etc. I obsessively memorized and absorbed every single word and note of these records, finding things to love about even the lesser efforts. I loved the idea of Love almost as much as the music itself — a fiercely intelligent, musically diverse, multi-racial unit who were so supremely cool that even The Doors looked up to them…

1969’s Four Sail was the real revelation to me, though; it was generally written off in those days as being a disappointing follow-up to Forever Changes — largely because Arthur had replaced all of the original members other than himself by this point, and how could the band possibly be as good without the ethereal presence of beautiful white guy Bryan MacLean? — but I thought it was every bit an impressive listen in its own ornery way. Plus, it contained the exact sort of searing guitar interplay I’d hoped to find on Forever Changes. (I once called Four Sail “Forever Changes’ unwashed biker cousin” in the pages of Ugly Things, and it’s an assessment I continue to stand by.)

Love was a major influence on my post-college band Lava Sutra. I tried to sing like Arthur, stole several oddball chord progressions from his songs (and even the entire guitar intro to “Robert Montgomery”) for our own compositions, while Love classics “My Flash On You,” “Can’t Explain,” “You I’ll Be Following,” “Gather Round” and the heavied-out Out Here version of “Signed D.C.” all made it into our setlists at some point. However, I was wise enough to realize that Arthur’s innate ability to poetically mix beauty with horror, wonder with brutality, and street-smart attitudes with cosmic observations was well beyond my reach; the man had a serious lyrical gift, and I wasn’t even going to try to emulate it.

By this point — the early ‘90s — Arthur was laying extremely low in Los Angeles, but we’d heard word of him occasionally resurfacing for the odd gig. So in August 1993, when I left Lava Sutra and moved from Chicago to Los Angeles, seeing Arthur Lee live was tops on my to-do list. I didn’t have to wait long; within a week or two of arriving, I saw an ad in the paper for an upcoming Arthur Lee gig at the Palomino, and practically ran to the nearest Musicland outlet to snap up some tickets for me, my girlfriend Carole and my Uncle John, since I was so afraid that the show would sell out on us.

I shouldn’t have worried; by that time, Arthur was pretty much L.A.’s forgotten man , and there couldn’t have been more than 50 people at the show. I held my breath, hoping that I wouldn’t see one of my all-time rock heroes embarrass himself, but kept my expectations low just the same. Instead, I was pleasantly surprised — shocked, even — by how good Arthur looked, how beautifully he sang, and how well his band of young backing musicians seemed to know Love’s more complex material. I wrote a rave review of the show for the LA Reader, and after attending several more gigs eventually got to know the guys in his band, some local cats about my age who also made music of their own under the name Baby Lemonade.

Mike Randle, Baby Lemonade’s dynamite lead guitarist, became an especially dear friend of mine — one I’m still close with to this day. Mike has the best Arthur Lee stories, but I’m not gonna share any of those here; Mike’s been working on a book that will include them all, and I don’t want to steal his thunder. But I do have a few Arthur stories of my own…

I was honestly scared shitless of Arthur from the very first time I was ever in the same room with him. Sure, some of it was just me being intimidated/starstruck by someone whose music I adored, but the dude also had a presence that was seriously heavy. Plus, I’d heard many rumors and stories through the years about how he would cruelly fuck with people just for the sheer hell of it — even if it meant shooting his own career in the foot in the process — and I really didn’t want to come face-to-face with that aspect of his personality. At the second gig we attended, I asked Carole to get Arthur’s autograph for me, because I was just too freaked to go up and ask him myself. She did, and told me when she came back to our table with a signed CD booklet that he’d seemed really quiet and nice. Hmmm… I didn’t buy it.

Every Arthur Lee and Baby Lemonade gig I saw in late ‘93/early ‘94 was absolutely brilliant. There was one particularly memorable one at a fancy-schmantzy Sunset Strip nightclub called Bar One, which for whatever reason had one night a week hosted by former Motley Crue frontman Vince Neil, who wound up booking Arthur and the boys to play on one of his nights. Vince and his band were supposed to play afterwards, but Arthur’s set was so ferociously, jaw-droppingly badass that they decided not to even bother. There was no stage in the place — the bands just set up in a corner of the floor — but I swear to the gods that I actually saw Arthur levitate during an extended jam on “Singing Cowboy,” floating over to where me and my friend Eric stood to shake his maracas in our face, grinning evilly all the while.

Unfortunately, as word got out that Arthur was “back,” and he and Baby Lemonade began to play larger venues to bigger crowds, he began to act more erratically onstage. It was not unusual for him to pause between songs to tell any number of O.J. Simpson jokes, or offer “private guitar lessons” to an attractive woman in the audience. And then there was that time when he was booked on a bill with L.A. psych legends Spirit — who at this point were basically just guitarist/singer Randy California, drummer Ed Cassidy, and somebody covering the rest of the parts on a synthesizer. While I was watching Spirit’s opening set from next to the soundboard, Arthur came up beside me and began to heckle them loudly and mercilessly from where we stood — and after every jibe, he’d turn and elbow me hard in the ribs with a hearty “Heh heh!” For instance…

Randy California [introducing a cover of “Red House” by Jimi Hendrix]:

You know, the thing about Jimi, man, not a lot of people know this, but he loved children, man. Jimi really loved children.

Arthur Lee [loud enough that the whole damn room can hear him]:

He hated you! He hated you! I know — he told me! [To me] Heh heh heh! Got him good that time!

Of course, I always wanted to interview Arthur about Love’s sweeter days, even though I knew that it was probably a fool’s errand. I was trying to get my foot in the door at MOJO in those days, and figured an Arthur interview would be a sure-fire way in, so I pitched it to Barney Hoskyns, one of the editors there at the time. When Barney replied that they could indeed use a short interview about the making of Forever Changes, I asked Mike to put me in touch with Arthur’s then-manager so I could set something up. After a week or so, the manager got back to me with a phone number for Arthur and a time to call him.

I was nervous as hell. For one thing, this was Arthur Lee. For another, this was for MOJO. And to make matters even more nerve-wracking, this was also the first-ever phone interview I’d done with anyone; I remember frantically running over to the Radio Shack on Wilshire Boulevard to buy a suction-cup microphone that I could attach to the receiver and then to my blocky hand-held cassette recorder, and praying that it would actually work.

It would have been so cool if the interview had gone well… but alas, it did not. From the moment he picked up the phone, Arthur was obviously in a foul mood; either he had not been informed of our interview, or he’d completely forgotten about it, or maybe he just wanted to hear me squirm.

“Who gave you my number?” he demanded. I told him that I had set up the interview with his manager, who had given it to me. “Let me tell you something, man,” he replied testily, “[name of manager] is not my manager. And he is not my father, my brother or my mother, either.”

Okay, I said, but I still wanted to interview him for MOJO magazine, so —

“Look here,” he cut me off. “You’re calling me when I’m busy watching The Beverly Hillbillies! This is my time!”

I honestly can’t remember if I convinced him to stay on the line with me, or if I called him back after The Beverly Hillbillies drew to its hilarity-filled conclusion, but the interview did eventually get done. Getting each answer from him was like pulling teeth, however, and on the rare occasions when he did offer up a lengthier response it was mostly to talk shit about everyone else who’d been involved with Forever Changes. A short Q&A eventually ran in MOJO, but it wasn’t either of our best work.

Still, as mortifying as the whole experience was, I hung on to Arthur’s phone number, simply because I got a kick out of being able to flip through my office rolodex and see it pop up, something I couldn’t have even conceived of a decade earlier. Ditto for the voicemail I got one day on my office line from Alban “Snoopy” Pfisterer, who had played drums on the first Love album and keyboards on the second; he was looking to get in touch with Arthur, so I figured I should probably call Arthur and pass Snoopy’s info along, rather than just give out Arthur’s number. Much to my relief, I got Arthur’s answering machine, so I just left a message to the effect that Snoopy wanted to talk to him. I gave him Snoopy’s number, and out of habit I must have left my own.

About two months later, I was down in Austin for the 1996 SXSW Music Festival; one evening, exhausted from a long day of trying to fit as many shows into my itinerary (and as much beer and barbecue down my gullet) as possible, I retired early to my hotel room and decided to check my work voicemail. “Hey man, it’s Arthur,” growled a familiar voice. “Call me back!” Well, what the hell…

The Arthur I got this time was the polar opposite of the one I’d tried to interview — soft-spoken, funny and exceedingly charming. He couldn’t seem to remember why he’d called me, but he definitely remembered who I was. “How are things over at The Reader?” he asked. I told him that I’d left him a message a while back about Snoopy, though I was currently in Texas and didn’t have his number on me. “Oh yeah, that Snoopy, he’s a trip,” Arthur chuckled. I expected him to hang up at that point, but he kept talking; about new songs he was writing, about the Baby Lemonade guys, about switching back and forth between being a vegetarian and a carnivore. I don’t know if he was high, or bored, or lonely, but he clearly wanted to shoot the shit. And it’s not like I really had anything better to do at that point in the evening than shoot the shit with Arthur Lee…

That was the last time I ever spoke to Arthur. His arrest on the firearms charge came soon afterwards, followed by the court case, the prison sentence, the comeback and the leukemia. He was a brilliant, deep and profoundly complicated man; I certainly got to see his unpleasant side, but I’m thankful that I got to experience his lighter and sweeter side as well, if only for a 20 minute phone call. Best of all, though, is that I got to see him in action when he was hungry again, and when he was backed by a band that not only knew his stuff cold but could push him to give the music his all. Ultimately, that’s the face of Arthur Lee I will always see.

Fantastic article in every way Dan, a great inspiration for Love! I would suggest you and I do a Crossed Channels episode on this act except you might already have suggested it.

This was an amazing treat. Thanks for posting this.