Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers!

Tuesday’s post about some of my favorite TV themes of the 1970s clearly struck a chord, as it’s already become — next to my appreciations of the late Greg Kihn and the possibly-defunct Aerosmith — one of the most-read things I’ve posted here at JTL this summer.

Thank you all for reading my stuff, and for supporting this Substack by subscribing (free or — for just $5 a month or $50 a year — paid), sharing favorite posts with your friends, or just leaving a positive comment when the spirit moves you. I truly appreciate being able to find an audience through this platform, and am grateful that you’ve chosen to become a part of it.

In keeping with the 1970s TV theme, please join me now on a quick trip to the other side of the pond, where I spent four months immersing myself in UK television shows during the last third of 1974…

There are many things I love about living in England while my dad is on sabbatical at the University of Warwick in Coventry, but British TV isn’t one of them. Not that the regular programming is bad, per se — some of the shows, like the children’s adventure series Chinese Puzzle, were actually quite good — but I desperately miss watching my favorite American shows, and I can never seem to get the hang of the UK TV schedule like I did back at home.

Like, why is The Benny Hill Show on at a particular time on a particular night one week, and then the same time slot is occupied the following week by some horrid variety show with leggy dancers prancing around in sequins and guys in white turtlenecks crooning things like, “Look at the beautiful ladies/They are the Hollywood Girls…”?

Still, I never miss an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which is currently in its fourth and final season. My father, an ardent Python fan since his sabbatical a few years earlier at Cardiff University, took my sister and me to see And Now For Something Completely Different when it played Ann Arbor in 1973, so I’m already fully on board with Pythonesque absurdity, even if — as with MAD magazine — I’m still a little too young to understand at least half of the references. For the rest of my life, nothing will transport me back to the little front room in our Leamington Spa rental quite as quickly as the John Philip Sousa march “The Liberty Bell,” better known in modern times as Monty Python’s opening credit music.

Now let’s flash forward to the early eighties, where my high school friends and I are watching Monty Python re-runs every Sunday night on PBS. As dutifully as we watch Saturday Night Live, Python and SCTV are still far and away the two biggest televised influences on our warped teenage senses of humor. At one point during my junior year, we even convince our English teacher Mr. Duffy to screen the “Michael Ellis” episode of Python for us in class, since its Victorian poetry reading scene dovetails nicely with the Shelley and Keats in our curriculum.

Monty Python is immediately followed on PBS by Dave Allen at Large, which always presents me with something of a quandary. On the one hand, I want to keep watching TV, and thereby continue procrastinating the completion of whatever homework is due on Monday morning. On the other, Dave Allen at Large is so awful that it makes doing homework seem kinda preferable; whenever my friend Jason and I watch the show together, we usually manage to correctly predict a skit’s punchline well before it’s actually delivered.

But man, the theme music from Dave Allen at Large is absolutely killer. Opening with an attention-grabbing horn fanfare, it quickly cuts to a cool organ groove that totally telegraphs “sixties mod” to me, even though I’m almost totally ignorant as to specific reference points for this kind of music. It’s the kind of tune that makes me want to immediately don my sharpest sharkskin suit and go struttin’ along the lakefront, though of course 10:30 on a Sunday night is far too late for that kind of behavior. In any case, Jason and I agree that the Dave Allen at Large opening theme — and the vaguely op-art graphic sequence that it’s paired with — is well worth hanging around for, even if the rest of the show isn’t.

Flash forward again to the mid-nineties, a period when I’m reading British music monthlies MOJO, Q, Vox and Select from cover to cover every month. This, for me at least, is the golden age of the CD era, when record labels both large and small are beginning to open up the vaults and release all kinds of incredible vintage sounds that haven’t been commercially available in decades, or ever. UK and European labels seem far more aware of the demand for vault-trawling reissues than their US counterparts — Rhino and Sundazed are far out-classing the American major labels in the reissue game — so I keep a close eye on the reviews sections in the aforementioned magazines and make lists of new releases that I should be scouring the “Imports” bins for at my local record stores.

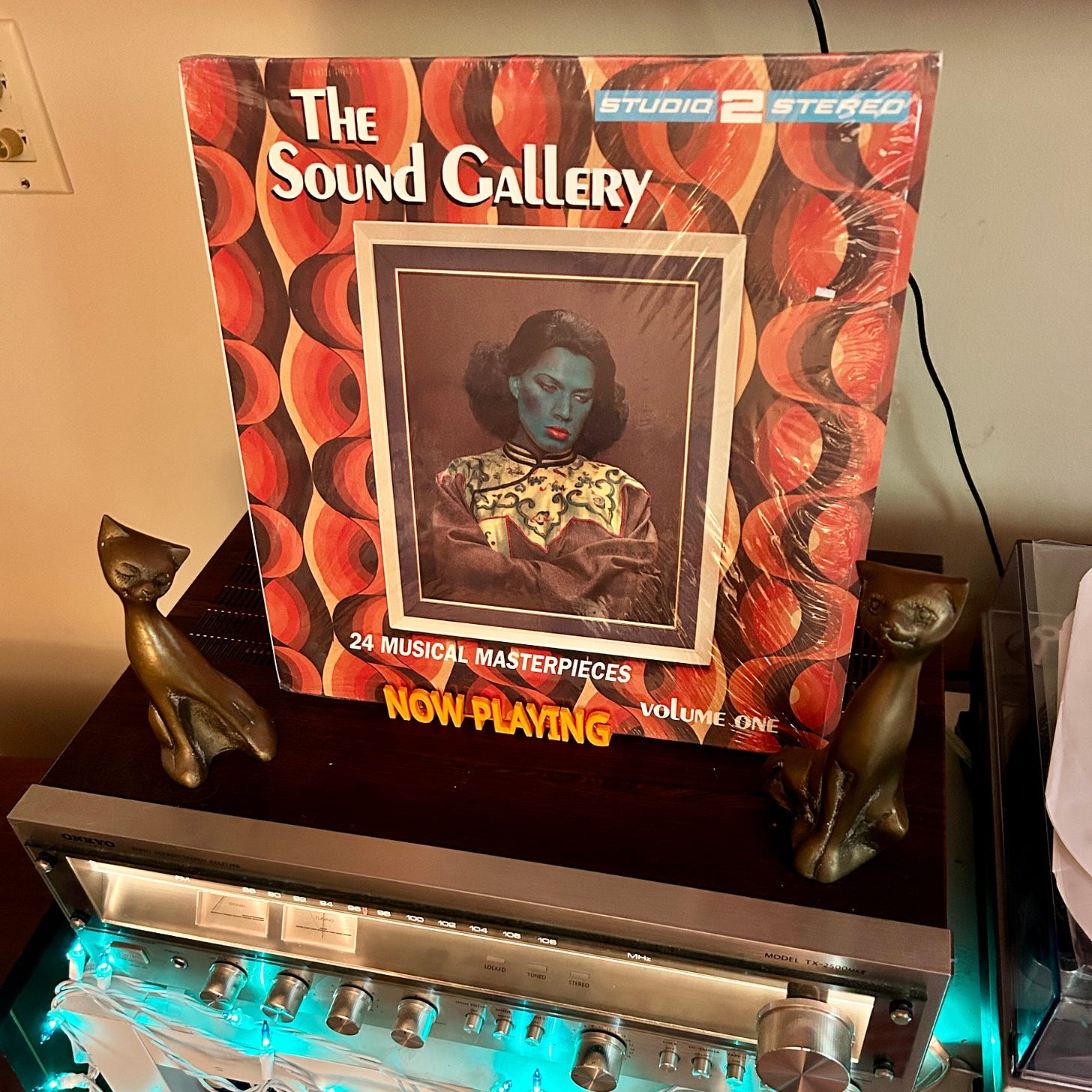

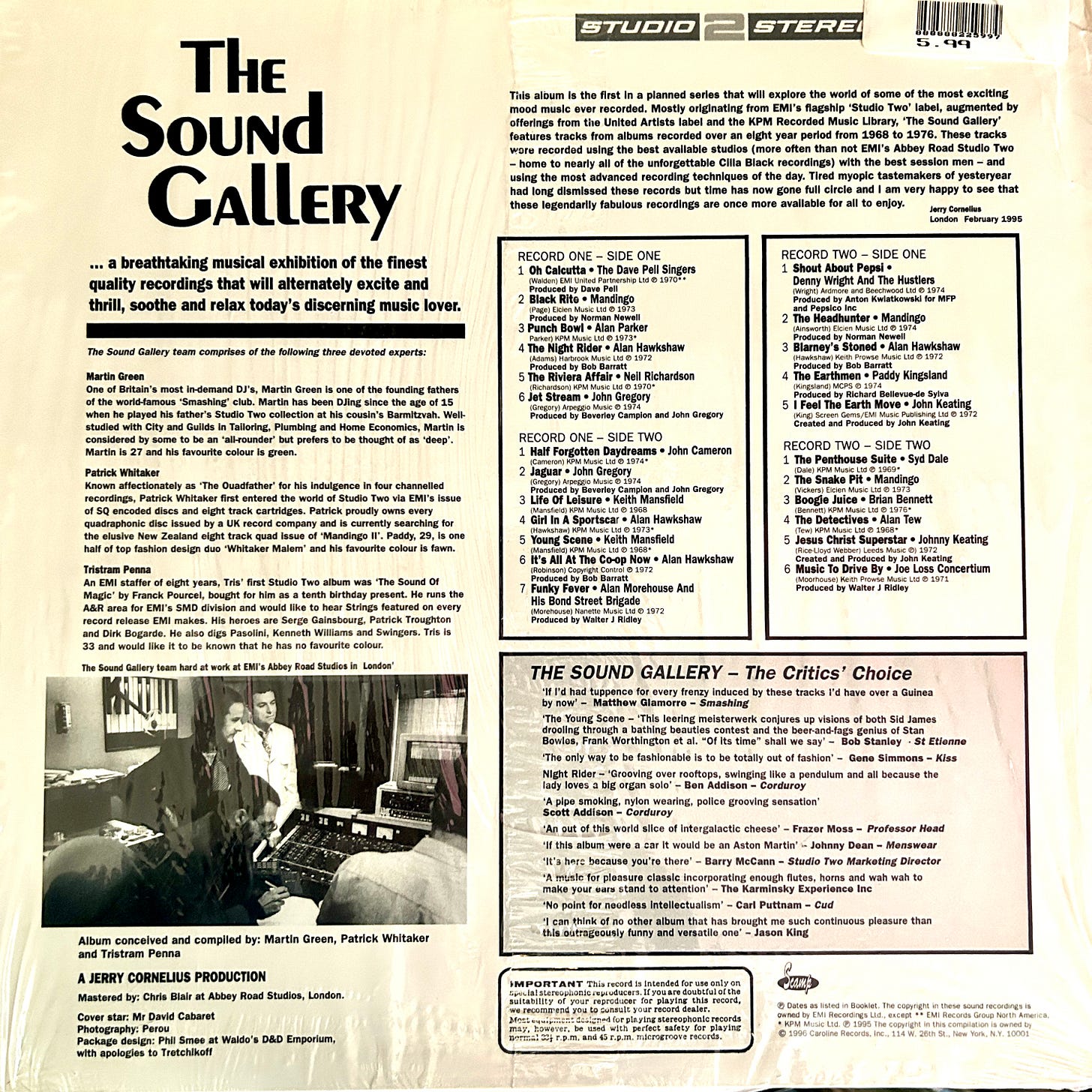

One day in the spring of 1995, I notice a single-paragraph review in the back of one of mags for a compilation called The Sound Gallery. The review takes something of a snarky tone, and drops some terms I’m unfamiliar with (“KPM,” “library music,” etc.) — but when it mentions that the collection contains Alan Hawkshaw’s “Blarney’s Stoned,” and that said song is better known as the theme from Dave Allen at Large, I immediately know that I have to grab it. I search all over L.A. for a copy of The Sound Gallery, finally special-ordering it through a friend and former co-worker at the Virgin Megastore. The import CD costs me $27.99, or about twice as much as a domestic release, but I don’t care. The Dave Allen at Large theme (which I haven’t heard in close to a decade at this point) will be mine!

That $27.99 will turn out to be some of the best money I ever spend on a record or CD. For while “Blarney’s Stoned” — written and recorded by Alan Hawkswaw — does indeed sound as fantastic as I’d remembered, it’s just the tip of the ice cube in the smoked cocktail glass. If “Blarney’s Stoned” transports me back in time to those high school Sunday nights, so many of the other 23 tracks on The Sound Gallery magically hurtle me back in time to late 1974, to a shabbily exotic televised world of Barclay’s Bank and Cadbury’s Chocolate commercials, glitzy variety shows, nudge-nudge-wink-wink humor and Z-Cars.

The reason they are able to do this, I realize upon reading the collection’s liner notes, is that a number of the instrumental tracks — such as Alan Parker’s “Punch Bowl,” Neil Richardson’s “The Riviera Affair” and Keith Mansfield’s “Life of Leisure” — were originally cut in the late sixties and early seventies for the KPM Recorded Music Library, which provided music for non-exclusive use in British television and film productions. It occurred to me that I’d heard many of these tracks as music cues in various TV shows and movies, commercial bumpers, etc., back in England in 1974, while a few of them had even migrated across the Atlantic, like “The Riviera Affair,” which was used as the opening theme for WOR-TV’s 4 O’Clock Movie.

Even the non-KPM tracks, like the Dave Pell Singers’ “Oh, Calcutta,” Johnny Keating’s “Jesus Christ Superstar” and John Gregory’s “Jet Stream,” gleam with a similarly cheesy-yet-aspirational vibe that I vividly remember from my brief but intense exposure to pre-punk British pop culture. (In fact, I’m pretty sure the showgirls at London’s Victoria Palace Theatre actually did perform a dance number to “Jesus Christ Superstar” between acts at the performance of Carry On, London! that my dad took us to in November ’74.) It’s the sort of music that conjures up images of driving a high-performance automobile to the airport for a martini-fueled transcontinental flight with a beautiful companion, and makes such a scenario seem like the most desirable thing imaginable.

Up until this point in my life, my interest in “easy listening” music has been largely limited to American sounds of the fifties and sixties: the faux Polynesiana of Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman, the hi-fi high wire acts of Juan Garcia Esquivel, the sunny and swinging Latin inflections of Herb Alpert and Sérgio Mendes. But now, these sleek, cinematic and even occasionally quite funky sixties and seventies jams from the UK are making me rethink everything I thought I knew about easy listening, and reminding me that these sounds were actually part of my childhood in a way that the American stuff never was.

Most of us music obsessives can point to one particular compilation that initially blew our minds and opened our ears to a whole genre or era, and served as our touchstone and guide as we ventured further into that field. Lenny Kaye’s legendary 1972 compilation Nuggets led the way for countless listeners, myself included, to explore the fuzzed out realms of 1960s US garage rock. In the mid-1980s, Atlantic Records’ multi-volume Atlantic Rhythm & Blues 1947-74 set massively expanded my understanding of R&B and soul music; and a few years later, Bam-Caruso’s multi-volume Rubble series introduced me to the paisley-draped joys of British freakbeat and pop-psych.

In the mid-1990s, The Sound Gallery effectively serves as my Nuggets of British easy listening and library music, turning me on to the brilliant likes of Alan Hawkshaw, Keith Mansfield and John Cameron, and directing me down countless KPM-related rabbit holes. During the seven years in the ’00s that I co-own a home in Palm Springs, The Sound Gallery and the artists it turned me on to will form a substantial portion of my poolside listening, and the Joe Loss Concertium’s “Music to Drive By” (definitely not to be confused with the album of the same name by gangsta rappers Compton’s Most Wanted) will be my jaunty go-to theme for toolin’ around town and watching the palm trees waving in the warm afternoon breeze.

In the decades that follow my Sound Gallery discovery, the many original KPM records will be reissued on vinyl, and I’ll occasionally add one (and then another) to my album collection. I’ll keep an eye out for a vinyl edition of The Sound Gallery, but never with much luck — the few copies that are up for sale on Discogs all seem to have migrated to Japan, and the cost of shipping is just too prohibitive.

And then, one day in the summer of 2024, a US vinyl copy of The Sound Gallery — released in 1996 by the cool but short-lived reissue label Scamp Records — suddenly pops up on my Discogs Wantlist alert. The record is practically in mint condition, and the seller is both here in the States and wants less than the 2024 equivalent of what I paid nearly 30 years ago for the CD. I think about it for about 30 seconds before I hit the “Pay Now” button.

The album arrives about a week later, and I dim the lights, pour myself a refreshing beverage, slap the first record on the turntable, sit back in my favorite comfy chair, and prepare to let the music wash over me. By now, I know every note of these tracks by heart, but something about hearing them again in the order that I originally heard them — and hearing them together on vinyl for the first time — makes me feel like I’ve been reunited with dear friends from 30 years ago. Or is it 40 years? Or 50? Whatever the number, it sure feels (and sounds) damn good to have them all back in my living room again.

You're so right on that last amazing era of rock, etc. - the too-brief golden age of CD reissues done right after that first horrible wave of CD transfers, Mojo was indispensable!

Such a great comp. I remember going on a real tear buying up all the "easy listening" comps that came out around this time. Being in London I was also able to listen to Jonny Trunk's radio show on Resonance FM that had an absurd number of deep cuts hidden within the selections. I'll admit now that because I used to also do a show on Resonance I mildly abused my privilege by getting a copy of one of the shows that just had too many killer selections on it. I'm sure you have already but if not, be sure to check Trunk Records that reissued anything from The Wicker Man soundtrack to even more obscure gems like Psychomania. All are incredible.