Rest in Power, Ramblin' Wayne

A funky farewell to one of my formative rock n' roll heroes

“Mom,” I asked one afternoon in October 1970, as we were driving down to the U of M campus to pick my dad up after work. “Where do the Pink Panthers live?”

As with most of the seemingly random questions that came out of my four-year-old mouth, there were very specific reasons behind my asking this one. I knew that the White Panther headquarters was over on Hill Street, just across Burns Park from where we lived, and I’d just heard on the news about a shootout at Black Panther headquarters in Detroit. And since The Pink Panther Show was my favorite cartoon at the time, it seemed only logical that the titular character and his tribe of similarly-colored cats would reside somewhere nearby.

I don’t recall my mom’s answer, but I do recall that it would be a dozen years or so before I finally understood the connection between the White Panther HQ, the “Free John Now!” signs that were posted all over Ann Arbor in 1971, and The MC5. My mind was completely blown by the realization that my 1967-69 tenancy in our first Ann Arbor apartment — over at the easily-memorized corner of Baldwin Avenue and Baldwin Place — had overlapped with the nearby presence of one of the most exciting and (as it would turn out) influential bands in the history of rock n’ roll.

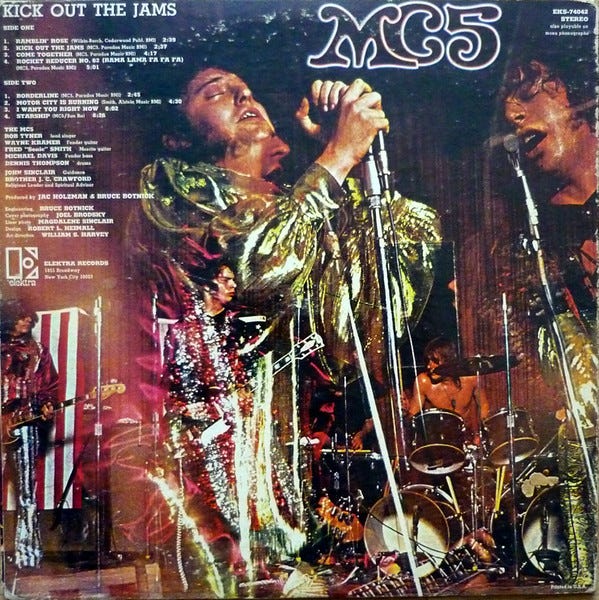

The MC5’s records weren’t easy to find in the early/mid-eighties, and thus they were one of many legendary bands I saw mentioned in the pages of CREEM, Rolling Stone, etc. well before I was ever able to actually hear them. But in 1984, I finally got my hands on their Kick Out the Jams LP — the censored version, with “Brothers and Sisters!” awkwardly dubbed in to replace “Motherfuckers!” — courtesy of the Rolling Stone Records cut-out bin. The band turned out to be everything it was hyped up to be, and more.

The music on KOTJ was raucous, sweaty, heavy, angry, explosive, exploratory, politically aware, sexually-charged, funny and fun — an addictive combination that seemed entirely alien and anathema to the slick and superficial Reagan Eighties that I’d found myself trapped in. The fact that these hairy dudes had essentially been my Ann Arbor neighbors just sealed the deal, and I pledged to stay alive with The MC5, even though the band itself was long dead. And one day, I promised myself, I would own a Gibson SG like the one Wayne Kramer was toting in the album’s back-cover photo collage. If Brother Wayne played one, I figured, it had to be thee ultimate rock n’ roll axe!

In the spring of 1988, after playing my final gig with my college band Voodoo Sex Party, I sold my trusty Hondo Fatboy to a friend, and took the resulting $250 (plus another $150 that I’d saved up) down to the nearest guitar shop in hopes of being able to purchase the SG of my dreams. Gibson had actually just reissued a sixties-style SG similar to Brother Wayne’s, but the store wanted $300 more for it than I had in my wallet; they could come down a bit on the price if I paid in cash, the salesperson told me, but not all the way down to what I could afford.

Not wanting to walk out empty-handed, and desperate for an SG of some sort, I went home instead with Gibson’s latest version of their storied “Standard Guitar” — a Ferrari red SG Special model with an ebony fretboard, three control knobs instead of four, and a pair of black humbuckers. It didn’t make me sound any more like Wayne Kramer than I already did (i.e., no more than I could convincingly sing like MC5 frontman Rob Tyner), but it was fun to play; and even though it wasn’t the SG of my dreams, I still thought it was pretty bad-ass.

There was one big problem, however: The damn thing resolutely refused to stay in tune. I’m sure my tendency to attack it like I was recording a live album at the Grande Ballroom didn’t help matters much, but the “tuning wars” I subsequently engaged in with Jason, my fellow guitarist in our Chicago band Lava Sutra — he also played an SG, though of an earlier vintage — were so epic that Homer would have surely written about them had he lived to witness the grunge era. When a friend who was roadie-ing for us at one of our gigs accidentally knocked my SG off its stand before the show, decapitating its headstock in the process, I took it as a cosmic sign to move on to a different kind of guitar.

Flash forward to early 1995, and I’m sitting in my office at the L.A. Reader, interviewing none other than Brother Wayne Kramer himself about his new comeback album, The Hard Stuff. I’d already met Wayne a few times via my friend and Reader colleague Mick Farren, who had been writing songs with Wayne for years — and whose friendship with him dated back to 1970’s ill-fated Phun City festival, which The MC5 had flown over to the UK to play, only to find that there was no money with which to pay them. This was, however, the first time I’d had the chance to rap with Wayne at length about his life and music.

It was a fascinating conversation, one which covered everything from his early worship of Motown’s session musicians (a.k.a. The Funk Brothers), his accidental discovery of guitar feedback (he’d left his guitar leaning up against his amplifier during a break from practice, and forgot to turn the amp off), The MC5’s various triumphs and travails, his prison stretch for dealing cocaine, his sobriety after years of heroin addiction, and of course the music he was now making. I wish I still had the interview tape.

That convo turned out to be just one of the many great interviews and casual chats I enjoyed with Wayne over the next 25 years or so. We crossed paths many times, shared a couple of stages and even worked together for a bit at the short-lived website MusicBlitz, for which he served as a talent scout and producer. I wouldn’t say we were good pals, but he always greeted me warmly whenever we ran into each other. He was a gregarious and screamingly funny conversationalist, and his flat southeast Michigan accent and wry sense of humor always sounded like “home” to me, even more than his wailing leads.

Wayne was a complicated dude, of course, and he definitely left some bad vibes and hard feelings in his wake — not least among some of his former mates in the legendarily fractious MC5 and those in their inner circle. Wayne’s lawsuit against the makers of MC5: A True Testimonial may have had its merits (and the documentary’s wide release may have ultimately been hampered anyway by the filmmakers’ inability to work out a deal for the music rights), but it put the “villain” target on his back for many folks as squarely (and perhaps as unfairly) as the anti-Napster crusade had put one on Lars Ulrich’s. So when Wayne passed away last week at the age of 75, I wasn’t entirely surprised that my brief Facebook tribute to the man prompted a handful of negative messages to pop up in my inbox.

At the same time, there’s no question that Wayne Kramer did a lot of good in the course of his life. Jail Guitar Doors, the non-profit organization he co-founded with British troubadour Billy Bragg and Wayne’s wife, Margaret Saadi-Kramer, has done incredible work via their mission of rehabilitating prisoners “through the transformative power of music”. And let us not forget how The MC5 was one of the few bands of their era who truly stuck their necks out politically, who pushed back hard against the “American Ruse” and the self-appointed guardians of the public morality even when doing so proved profoundly detrimental to their own career.

And let us also not forget how influential the band’s righteous brand of ramalama was on countless bands that followed, from the New York Dolls and Ramones on up to the present day, even though no one has ever quite managed to fully duplicate it. I mean, just watch this insane 1970 clip of “The 5” in action at Wayne State University’s Tartar Field, which is still my favorite live footage of any rock band not named The Who. And good god, check out Brother Wayne’s happenin’ moves; I can’t think of too many other guys who could combine fretwork and footwork with similar degrees of wildness. Wayne always brought it onstage, even into his 70s, as anyone who caught that last MC50 reunion/revival tour in 2018 can well attest.

My own encounters with Wayne were unfailingly joyful, inspiring and thought-provoking. “Right on to the motherfucking future,” he wrote on my copy of Back in the USA at the end of our first interview back in 1995, and he brought that same kind of energy and optimism to so much of what he did, even if his early life experiences (as detailed in his 2018 memoir The Hard Stuff) might have convinced a lesser person that it wasn’t worth the effort. It meant a lot to be able to tell him how much his old band’s music, energy and attitude had impacted me; I’m thankful that I had the chance to do so.

The Reader offices had closed by the time we finished our interview, so Wayne and I left the building together.

“Do you still have any of your guitars from your MC5 days?” I asked him, as we headed to our respective cars.

“Oh no,” he shook his head wistfully, “They all disappeared up my arm years ago.”

“Aww man, even the SG?”

“What SG?” he asked, looking confused.

“The one you played on the Kick Out the Jams album.”

“Oh no, that wasn’t even my guitar — I just borrowed that one from a friend for the photo shoot because it looked cool,” he laughed. “I never really liked SGs. Those things never stayed in tune!”

Rest in Power, Brother Wayne. You done kicked out the jams, and then some.

Amazing piece, brother. A truly fantastic final line as well, haha.

Very saddened by his death as well. I always liked the connection between Kramer and the Clash, one of my favorite bands.