Spin Cycle

The audio journey that took me back to nursery school

A child changes the music on the record player at the Ann Arbor Co-Operative Nursery School, 1955 [from the Ann Arbor News archives]

Hey, JTL readers — just wanted to give you the heads up that I’ll be taking a break until next week. Someone very near and dear to me passed away yesterday, shortly after I finished writing this entry, so please forgive the interruption. And, as always, tell those that you love that you love them, whenever you have the chance…

High fidelity audio was a concept that took me ages to really wrap my head (and ears) around. Back when I first fell in love with pop music, it was coming out of poolside PA systems and the factory-standard speakers in my mom’s mid-’70s Toyota Corolla, while the bulk of my listening over the next half-decade was primarily done via the quarter-sized speaker atop my clock radio. None of my parents, step-parents or grandparents owned stereo systems that were anything beyond your basic, budget-level setups, and my own first “system” — a low-end Sony direct-drive turntable plugged into a Panasonic “Platinum” boom box via a Radio Shack pre-amp — was singularly unimpressive from an audio standpoint.

But I didn’t really care. For me, the appeal of a song largely lay in the catchiness of the chorus, the badass-ness of the guitar riff, and the meaningfulness of the lyric, not in the “tones” of the instruments or spaciousness of the mix. In high school, I felt the same way about audio fidelity as I did about the technical proficiency of musicians— it was impressive, I guess, but also completely superfluous to my enjoyment of the music.

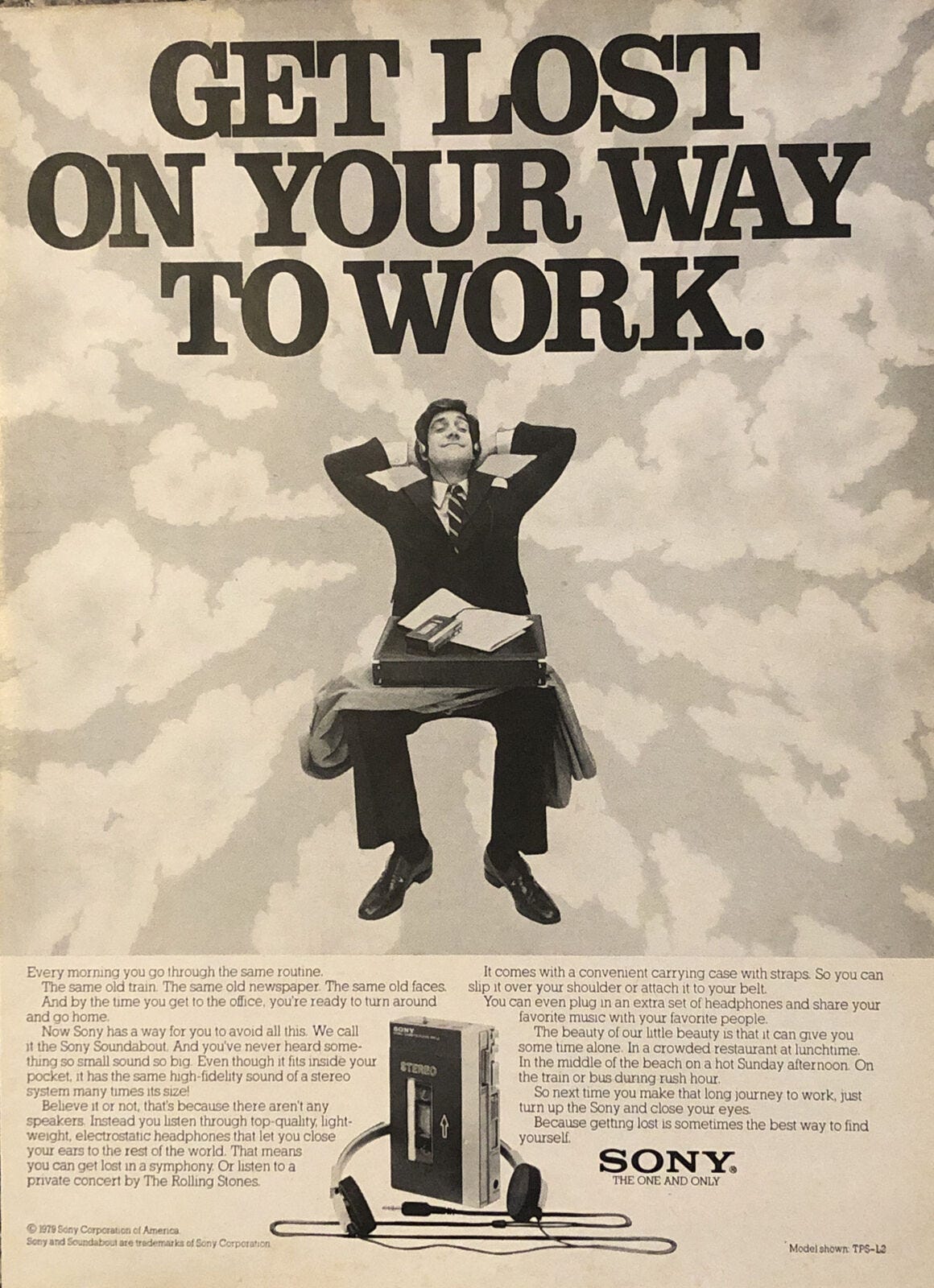

My attitude started to change a bit by the end of high school, when I acquired a hand-me-down Sony Walkman and began listening to tapes on my daily 40-minute commute to and from my job as an office clerk at the Beatrice Foods headquarters in downtown Chicago. I rarely bought pre-recorded cassettes (I hated the shrunken artwork and no-frills packaging), so the tapes I listened to on the 136 bus were primarily ones I’d recorded from my own records using the aforementioned low-budget system. Even so, the fidelity of it was solid enough that I could tell the difference between the cheap TDK-D tapes I used at first and the “high bias” TDK-SAs I eventually graduated to, and there were even a few times were I found myself genuinely carried away by the glorious sounds I was listening to on my foam-covered headphones — it was usually the jangly guitars of The Byrds and the soaring harmonies of The Turtles that did it — and maybe wishing that I could find a way to float a little deeper into the sonic mystic.

I never really pursued that line of thought, however. For one thing, much of what I was listening to by the time I got to college was older, unpolished stuff like The New York Dolls and The Clash, and newer, even rawer stuff like Hüsker Dü and The Replacements — nothing you needed the utmost in high fidelity to fully enjoy. For another, the kids in my dorm who did have really expensive systems seemed more interested in their equipment as cool gadgets and/or status symbols, which was a huge turnoff.

I regarded the coming of the compact disc with a similar level of suspicion; the promises of pristine fidelity cut no ice with me, as I was certain CDs were really just a plot by the major labels (or “The Man,” if you prefer) to rid the world of interesting music, since Sting, Phil Collins and latter-day Dire Straits seemed to be the only things coming out on CD at first. (I didn’t start buying CDs until 1989, by which time enough artists like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and The Flamin’ Groovies were being reissued digitally to allay my fears of musical genocide.)

In 1998, I used my first book advance to buy something I’d wanted since I was a kid: a jukebox for 45 rpm singles. I already had a pretty substantial singles collection at that point, but owning that sweet Wurlitzer 2800 sent my collecting into overdrive — not just because I loved being able to play my 45s one after another at the touch of a button, but because they sounded absolutely amazing through the jukebox’s tube amplifier. The songs — especially ones from the ‘50s and ‘60s — had a visceral presence to them that I’d never experienced before; I remember hearing Johnny Meeks’ guitar solo busting through the speakers on Gene Vincent’s “Lotta Lovin’,” and thinking it sounded like the voice of God itself.

(I got ten good years of use out of that Wurlitzer before dire financial straits forced me to sell it off; which was probably just as well, as I’ve moved nine times since then and getting that monster across the country would have been a right pain in the ass, but I still miss it and fantasize about someday getting another one. Alas, book advances generally aren’t quite so lucrative these days…)

But for whatever reason, I continued to stick with modern, digitally-oriented stereo set-ups until about five years ago when the penny suddenly dropped: Since most of the vinyl albums I was listening to on a regular basis were from the ‘70s, maybe I should see what they sounded like through actual ‘70s components — or at least, since I wasn’t ready to part with my tank-like Technics SL-1200 turntable, a ‘70s-vintage receiver and speakers?

The current Chez Epstein setup

My impulses, belated as they were, were absolutely correct: I’ve never heard my LPs sound as good as they do through my late-’70s Onkyo receiver and early-’70s Epicure speakers (and sometimes my early-’70s Pioneer headphones). And for the first time ever, that sound quality really mattered to me: Between the COVID pandemic and unexpected changes in my personal life, I found myself escaping into music more and more; I realized that the calm caress of a muted trumpet or the ribcage-rattling embrace of a Hammond B-3 or the brain-searing graze of a fuzzed-out guitar were more healing for me than any therapy session. And for them to really work on me, I needed them to be rendered as close-to-life as possible.

But once I relocated to the Hudson Valley last fall, those musical therapy sessions came to an end. I was cooling my heels at my mom’s place for a couple of months while trying to find a pad of my own, and — comfy and hospitable as the situation was — she had neither a stereo of her own nor room for me to set mine up. My record collection was temporarily in storage, but I was still bringing home LPs and 45s from local thrift shops and record stores, because digging through dusty old piles of wax is another activity that I find fabulously therapeutic. But how could I play these new acquisitions — or get my needle-in-the-groove fix — without a stereo?

Inspiration came, as it so often doesn’t, via Facebook. A friend of mine posted about how, back in his teaching days, he’d played Charlie Parker and other classic jazz records for his students on one of those classroom Califones. These same portable “suitcase” record players had been part of my own education from nursery school —where my teachers spun such child-friendly LPs as Black Beauty, 101 Dalmations, The Wheel On the School and 10,000 Leagues Under the Sea during our naps — on up to junior high school, when my friends would play their newly-acquired 45s during lunch time. Califones were built like friggin’ tanks, and I figured they couldn’t be any worse-sounding (or rougher on my records) than those crummy Crosleys you see everywhere, so off I went to eBay.

Alas, like so many other items from my youth, Califone record players have now become pretty collectable, and I wasn’t finding any ones in good working order for under a hundred bucks plus shipping. But after doing a little additional research, I discovered the Audiotronics brand, which manufactured similarly sturdy classroom record players in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but which doesn’t have the same collector cachet as Califone. I found one on eBay that was in near-mint condition — it had been discovered in the back of a church storage room — and listed for $25 plus shipping from South Carolina. The entire transaction would cost me less than $60, and I’d soon be able to play “the Devil’s music” on former church property? I was all over the “Buy It Now” button like white on rice.

Less than a week later, the record player arrived, and turned out to e just what the doctor ordered. The “Bi-Directional Sound” — basically just speaker grilles on the front and back of the unit — wasn’t anything that would make an audiophile drool, but it sounded loud and powerful, especially when playing old mono 45s.

At first, I thought that the Audiotronics would simply be a stop-gap measure to get me through a tough transition period, but it’s still getting a semi-regular workout these days in my new home office, where it sits on a cabinet next to my desk. It’s handy for playing beat-up records that would just sound too scratchy on my higher-end home system. And for the first time in my life, thanks to its old three-speed mechanism, I have something to play 78s on. Not that I ever collected 78s, of course… but now, whenever I see a tasty one in a thrift store bin, I have an excuse to bring it home with me. Because as I implicitly understood from the get-go, music doesn’t have to sound great to sound great.

I see the new Robyn Hitchcock album in the photo. Hope you’re enjoying it, I’m really digging it.

Absolutely true. It will always sound great if you have an emotional connection to the music. I’ve gone from listening to George Jones on my Uncle Bill’s 8 track to higher end component stuff in the 70’s and now here I am with my phone and blue tooth speaker. Really digging the same songs and feeling the same way I did 50 years ago. I especially like that the older stuff was mostly written in a major key! The sun is out and the windows are rolled down as I listen to the The Beach Boys sing Surfer Girl. Lord have mercy how could one go wrong! Thanks again Dan for your great post.