Thick As Thieves

Why the US version of The Jam's Setting Sons LP is better than the UK one — and why that's a hill I will totally die upon

Greetings, Jagged Time Lapse readers!

Before we get down to business, I wanted to thank everyone who has subscribed to this Substack — we officially passed the 600-subscriber mark yesterday, which I’m pretty damn stoked about!

If you’re reading this but haven’t yet subscribed, a free subscription to JTL is the best way to ensure that you are notified whenever I create a new post — it will be sent straight to your email the minute it goes live! I also regularly share my posts on Facebook and Instagram; but social media algorithms being what they are, only a small percentage of folks who “friend” or “follow” me on there ever see them.

And if you enjoy what I’m doing here enough to want to read additional bonus content — as well as actively support the writing of all the good stuff that I post for free — a mere five bucks a month (or even less if you plunk down for a full year’s paid subscription) will get you full access to all JTL paid posts and archives, as well as help keep the lights on here at my humble mountain abode.

But if you can’t swing that (and believe me, I know times are tight for a whole lot of us), sharing JTL posts that you dig with folks who you think might also dig ‘em is enormously helpful to the cause, as well. In any case, thank you all for your support!

So, then…

I was enjoying a couple of pints last week with my new pal Tony Fletcher, esteemed author of such essential music tomes as Moon: The Life and Death of a Rock Legend and All Hopped Up and Ready to Go, when talk turned to The Jam. We are both massive fans of that band, and have been so since our teens; we also share a deep emotional connection with that most-maligned of all Jam albums, 1977’s This Is The Modern World, though more on that in a later post.

There are vast differences in the “origin stories” of our Jam fandom, however. Growing up in the UK, Tony not only saw the band numerous times on their way up, but he also eventually became part of their inner circle and even worked for Paul Weller’s short-lived Jamming! record label. I was just an Anglophilic American teen who loved this none-more-English band from afar; the most intimate “interaction” I ever had with The Jam while they were still a functioning unit was picking T-H-E-J-A-M as the PIN code for my first ATM card.

Too young and clueless to discover most of the band’s albums until well after they were released, I was likewise of insufficient age to attend the few gigs they ever played in my general vicinity — with the exception of their Aragon Ballroom stop on The Gift tour, which I badly wanted to go to but couldn’t because I had a final Latin exam the next day. (This sadly turned out to be their final US swing, though we didn’t know it at the time…)

Tony is not someone I would ever want to take on in a head-to-head Jam trivia challenge… which is why it fairly blew my mind the other night when I managed to bring up a Jam factoid that blew his mind: Namely, that the original US version of The Jam’s 1979 LP Setting Sons had an entirely different running order than the UK release.

Side One on the UK version of Setting Sons is Side Two on the US one, and vice versa, but this isn’t just a case of accidental pressing-plant flippage; the flipped track order is listed as such on the back artwork of the US LP, which also adds “Strange Town” (a non-LP single in the UK) to the proceedings. Someone at US Polydor clearly put some thought into this — though the thinking behind the decision has never been publicly revealed or explained, at least to my knowledge.

Tony was, as the Brits say, fairly gobsmacked to learn about all this — he’d never seen the above discrepancies mentioned in any Weller interview or any history of The Jam. He was also fairly intrigued by my assertion that the US track order actually works better than the UK one, and challenged me to make that case in print.

This one’s for you, Tony…

I bought my first copy of Setting Sons on something of a whim. The Jam was a band that got very little airplay on US radio, so it was difficult to hear them over here unless you knew someone who was already a fan. A friend of mine had turned me on to This Is The Modern World, and I’d gotten hip to The Gift because WXRT in Chicago was playing “Town Called Malice” pretty regularly at the time of its 1982 release, but the rest of the band’s catalog was a complete mystery to me. I picked Setting Sons for my next Jam album — despite not recognizing a single song in its track listing — simply because I thought its cover (which features what I would later learn was Benjamin Clemens’ 1919 sculpture The St. John’s Ambulance Bearers) looked appealingly tough and grim.

I didn’t know at the time that Paul Weller had initially conceived Setting Sons as a concept album about three boyhood friends whose lives drastically diverge as the result of a war, or that he’d eventually scrapped this idea due to some young fans giving him shit about making a concept album (something which was then considered the province of self-indulgent prog bands, or doddering thirty-something dinosaurs like Pete Townshend), and possibly also because he’d simply run out of time to fully flesh it out before the recording sessions started. Nor did I realize that some of Setting Sons’ songs were holdovers from Weller’s initial concept, though some of them weren’t. In any case, none of that mattered, because the album painted a very vivid picture for me even without the help of any backstory.

The US version of Setting Sons opens with the acerbic rumble of “Burning Sky,” a song which takes the form of a “catching up” letter from one old friend to another. The correspondence takes a condescending tone pretty much from the outset (“How are things in your little world?”), and further intensifies as the song unfolds. The author recalls the good times and shared ideals of his youthful friendship with the letter’s recipient, then disparages those things as concerns that now seem rather callow and insignificant in light of his current corporate priorities. (“There’s no time for dreams when commerce calls,” he sniffs.)

It’s a perfectly-pitched character study, one which calls out the encroaching “profit above all” mentality that would come to define the Thatcher (and Reagan) ‘80s, while also touching upon the way that professional, political, personal and philosophical concerns can come between once-firm friends as they grow older. Throw in the track’s hard-charging music, and “Burning Sky” makes for a particularly striking and dramatic album opener, one which really sets the tone and mood for what is ultimately The Jam’s darkest album. If Weller had followed through with his original concept, “Burning Sky” would have been a great way to open that version of the record, as well. “Girl on the Phone,” a mildly humorous tale of being harassed by a groupie/stalker that leads off the UK edition of Setting Sons, feels pretty flimsy by comparison.

Though “Smithers-Jones,” the US album’s second track, had previously been released (in a stripped-down band arrangement) as the b-side of “When You’re Young,” the orchestral version of Bruce Foxton’s finest songwriting effort fits in beautifully here, both musically and thematically. The titular character (who doggedly slaves away at his office, only to find that the promotion dangled in front of him has turned into a pink slip) could be the same guy who penned “Burning Sky,” now finding himself on the pointy end of the corporate greed he once championed. Or he could be one of the other two friends from Weller’s original story, who tried to follow a similarly buttoned-down path but wasn’t savvy or cutthroat enough to successfully climb the corporate ladder.

“Saturday’s Kids,” the next track, seems like a fond flashback to more carefree youthful days, the ones that bonded the the album’s protagonists back when they were just working-class teens living in council houses and wearing v-necked shirts with baggy trousers. “Eton Rifles,” one of the hardest-hitting tracks The Jam ever recorded, pits those same kids against their snottier, wealthier counterparts in a battle that also serves as a metaphor for the British class system. Though again not necessarily written as part of Weller’s original concept, the character in the song who gins his mates up with revolutionary rhetoric — then skips out while they’re getting their asses kicked — could well grow up to become the corporate tool of “Burning Sky”.

Side One of the US Setting Sons ends with a nicely rocked-up version of Martha & The Vandellas’ “Heat Wave,” which closes Side Two of the UK album. Though the track’s jovial mood feels really out of place on this heavy and dour record, it makes more sense to me placed at the end of the first side, where — combined with “Girl on the Phone,” which begins the second — it works as a brief and welcome respite from the album’s almost-overwhelming gloom. To my ears, these are by far the two weakest tracks on Setting Sons, so why in hell would you open and close such an acutely-felt, thought-provoking album with them? (I’m looking at you, UK track listing!)

I’ve heard it suggested that “Heat Wave” is tacked on to the end of the UK album as a nod to how The Jam would close their shows with covers of Motown chestnuts. But it’s one thing to want to send the punters home in a festive mood; it’s quite another to diffuse your album’s dark power by closing with a jarring blast of “Woo hoo — party time!”

During our conversation, Tony seemed especially confused/appalled by the US version’s inclusion of “Strange Town,” a single that already been out for nearly a year in the UK before Setting Sons was released in the States. I can’t really make a good case for its presence, other than that it’s a great song that I probably wouldn’t have otherwise heard — at least for a few more years — if it hadn’t been included here, and that “Strange Town”’s snapshot of urban suspicion and alienation meshes reasonably well with the dystopian themes running through most of the album.

Still, if US Polydor wanted to add a non-LP single to Setting Sons, a far better choice would have the brilliant “When You’re Young,” which was released as a single between “Strange Town” and “Eton Rifles,” and whose lyrics seem almost tailor-made for Weller’s original album concept.

“Thick As Thieves,” which follows “Strange Town” on Side Two of the US pressing (but is the second song on the UK’s Side One), is quite clearly one of the songs Weller wrote for his “three friends” story, as well as its emotional centerpiece. It’s also one of the best things The Jam ever recorded, a superbly observed meditation on how young men often idealize/romanticize their early friendships, then turn out to be emotionally unable/unequipped to maintain them into adulthood. I myself can never hear this song without thinking of several dear male friends from high school — though thankfully, I’m still in fairly close touch with most of them, save for one who was taken way too early.

I also own a rare mis-pressed copy of Snap!, the 2-LP collection of The Jam’s hits, b-sides and key album cuts, which features “Thick As Thieves” at the end of Side 2 and the beginning of Side 3. And you know what? I’m totally cool with that, because this is a song I will never mind hearing twice in a row.

I remember reading an excerpt many years ago from a 1960s British music paper interview with mod-psych legends The Creation, in which they speak of forthcoming songs they’ve written called “Closer Than Close” and “Private Hell”. No such Creation songs were actually released, but I’d be willing to bet my Ben Sherman loafers that Weller (a big Creation fan) saw that same back-issue and decided to write his own “Private Hell” as a result — after all, the Setting Sons track of the same name begins with the lines “Closer than close…”

“Private Hell” is one of the most intense things The Jam ever waxed, a tightly-wound second-person study of a completely unfulfilled middle-class housewife suffering from empty nest syndrome and valium addiction, among other maladies. This song probably wasn’t written for Weller’s original Setting Sons concept, though the woman’s son who’s briefly referenced here (“Think of Edward/Still at college/You send him letters which he doesn’t acknowledge”) could easily be one of the three friends from that story.

As we leave Weller’s valium housewife teetering on the edge of a complete mental breakdown, Setting Sons ushers us into “Little Boy Soldiers,” a sardonic mini-opera about the pernicious myths of empire, colonialism and military might.

Come on outside I'll sing you a lullaby

Or tell a tale of how goodness prevailed

We ruled the world we killed and robbed

The fucking lot but we don't feel bad

It was done beneath the flag of democracy

“Little Boy Soldiers” was definitely one of the songs penned for the original Setting Sons album, and bootlegs from the album’s recording sessions apparently point to the song — or at least parts of it — originally being employed as a recurring motif throughout the album. (Alas, recurring motifs were an absolute no-no in the post-punk rulebook.) Was the young soldier sent home “in a pine overcoat with a letter to your mum” one of Weller’s three protagonists?

It’s hard to say for sure, but what does seem certain to me is that a song with this level of darkness and complexity works far better as the penultimate song of the album than it does as the penultimate song of Side One. “Eton Rifles,” the song which occupies this spot on Side Two of the UK edition, is dark but not this dark, and the presence of “Little Boy Soldiers” on UK Side One makes that version feel really unbalanced for me; the entire album should be leading up to bleak one-two punch of “Little Boy Soldiers” and “Wasteland,” as opposed to relegating them prematurely to the end of Side One.

Ah yes, “Wasteland”. What a brilliant fucking closing track… at least on the US edition. The recurring recorder riff is like a pied piper leading you back to a happy place from childhood, but that place turns out to be the local dump — or, in the bigger picture, perhaps a once-beautiful and hope-filled place that’s been befouled and destroyed by human greed.

And there amongst the shit - the dirty linen

The holy Coca-Cola tins - the punctured footballs

The ragged dolls - the rusting bicycles

We'll sit and probably hold hands

And watch the rain fall - watch it - watch it

Tumble and fall - tumble and falling

Like our lives - like our lives

Just like our lives

In my imagining of Setting Sons, “Wasteland” is where the three old friends (or two of them, if one didn’t survive the war) finally meet again, and realize that all the other forces that motivated them — patriotism, profits, politics, etc. — were actually a crock of shit, and that love (brotherly or otherwise) is the only thing that ultimately means a damn. It’s too late to save themselves, or maybe even their country or planet, but this belated epiphany nonetheless brings them a certain amount of grace and peace.

Which, to me at least, seems like a perfect and profound way to end the record. But hey, Paul Weller apparently thought “love is like a heat wave” was the perfect sentiment to wrap this fearsome album up with — so what the hell do I know?

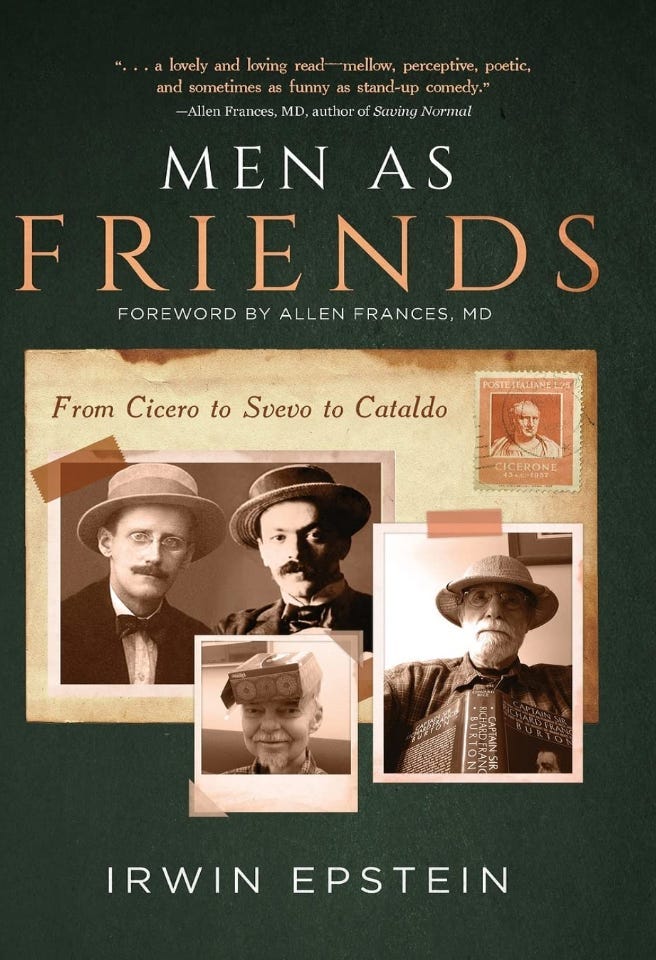

Oh yeah, speaking of friendships of the male variety: Men As Friends: From Cicero to Svevo to Cataldo, the new book from Irwin Epstein — a.k.a. my father — was officially released last week. It’s a really moving (and often extremely funny) examination of the many varieties of male friendship, as viewed through the lens of my dad’s life and career.

The book is available in hardcover, paperback and Kindle, and would make a great Father’s Day present — and really, a great present for any guy you know who doesn’t think that male friendship begins and ends with standing around the grill or getting together to watch “the big game”.

My dad did a great interview a few months back with the Oldster Substack, which should give you a pretty good idea of where he’s coming from. Suffice to say that I’m really proud of him, and really thankful that I lucked out with such a cool, smart and emotionally-present father. And if you like my writing, let’s just say that the apple didn’t fall far from the tree…

Yo Dan--you taught yourself how to read, but you taught me how to write. And you keep teaching me. Thanks--Dad

Thank you for this Jam tutorial!