Sérgio Mendes: "Yeah, I'm Lucky."

The Brasilian maestro on music, love and serendipity

Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers!

As promised in my most recent post, a list of Top 10 favorite Sérgio Mendes tracks, here is the (almost) complete transcript of my delightful 2021 interview with the brilliant Brazilian pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, who sadly left this earthly realm last week. But before we get into it, I wanted to say a few things:

1. I’ve had several readers call me out on Substack and social media for overlooking certain songs, albums or periods of Mendes’ career — and, quite frankly, they were right. I should, in retrospect, have made a list of Top 10 favorite Sérgio Mendes albums, because his discography is so extensive, so varied, and so filled with wonderful music. As I said before, my “sweet spot” is his original A&M years, but even then I didn’t get around to mentioning anything from 1968’s Fool on the Hill, 1969’s Ye-Me-Le, 1970’s Stillness — great Brasil ’66 albums all — or Brasil ’77’s A&M efforts Pais Tropical (1971) and Primal Roots (1972), all of which are far richer musically than their typically budget-friendly used bin price tags might imply.

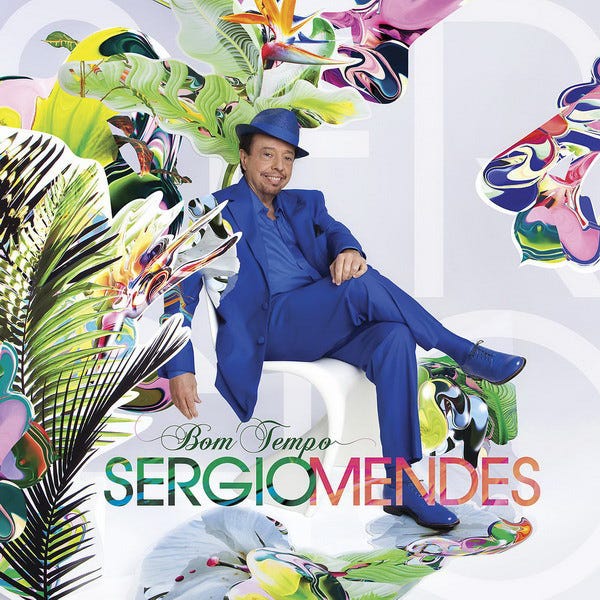

For those of you who prefer the more classic Bossa Nova sounds, check out 1964’s Você Ainda Não Ouviu Nada! by Sérgio Mendes & Bossa Rio (later repackaged as The Beat of Brazil), or The Sérgio Mendes Trio’s 1965 album Brasil ’65 (later repackaged as In The Brazilian Bag). And while it’s way too “eighties adult contemporary” for my personal taste, there are a whole lotta folks who swear by Sérgio’s self-titled 1983 album, the one with “Never Gonna Let You Go” on it. And then, of course, there are all the other records he did through 2019’s In The Key of Joy… So yeah, it’s impossible to truly do justice to an artist of this caliber or legacy with a puny Top 10 tracklist; I mostly just hoped that my previous piece would inspire folks to check out his music in the first place, or dig a little deeper beyond what they already know.

2. When I say that the following interview transcript is (almost) complete, that’s because said interview (conducted for FLOOD in June 2021) was unfortunately beset by all kinds of technical issues, both on my end — because I was so nervous that I actually forgot to turn on my tape recorder until after a few minutes of conversation had already passed — and on either the magazine’s or the publicity peoples’ end. The resulting video clip is still available on the magazine’s site, but it looks and sounds so crummy (and is such a truncated version of our actual conversation) that I’m not even gonna bother linking to it here.

3. As with most of the interviews I post on this Substack — previous ones have included memorable encounters with the disparate likes of Lemmy, Eddie Money, and Sean O’Hagan of High Llamas — this one’s only available in full to my loyal and lovely paid subscribers, without whom Jagged Time Lapse would not exist (or would at least be updated far less frequently). If you would like to support this Substack with a paid subscription of $5 a month (cheap!) or $50 a year (even cheaper!), you can do so by pressing the green button below. You’ll get full access to posts like these, as well as the entire JTL archive (which now contains well over 200 evergreen music-related posts), and the monthly episodes of the CROSSED CHANNELS podcast I do with my friend and colleague

, such as our most recent one on Kate Bush…Be aware, however, that Substack can be glitchy as fuck sometimes; so if your credit or debit card is declined, or you get a message telling you that you haven’t entered the proper amount of numbers (as happened to me a few days ago when I tried to re-up for a yearly subscription to a friend’s Substack), please come back and try again another day. Their technical issues, however annoying, usually get cleared up fairly quickly…

On, then, to the interview, which was conducted via Zoom; I was at my then-home of Greensboro, North Carolina, and Sérgio was at his pad in Los Angeles. It was done to promote a new one-hour PBS edit of the 2019 documentary Sérgio Mendes: Songs in the Key of Joy — directed by John Scheinfeld, whose acclaimed films include The U.S. vs John Lennon and Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary — which was retitled Sérgio Mendes & Friends: A Celebration, as well as Sérgio’s return to live performance after (like everyone else) having to sit out for over a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The doc (which can now be seen in its full running length on Tubi and other streaming sites) follows Sérgio’s journey as the earnest young pianist from Niterói, Brazil becomes a million-selling, Grammy-winning, Oscar-nominated, internationally-renowned bandleader, composer and arranger, so the interview took a similarly broad overview of his career. Sure, I would have loved to get more into the minutiae of his A&M days rather than talk about, say, his collaborations with the Black Eyed Peas, but we had a lot of ground to cover in just a short amount of time. And as became clear from our conversation, musical collaboration was one of Sérgio’s favorite things; while I was never particularly interested in Will.I.Am or his Peas pals, Sérgio was immensely (and justifiably) proud of the fact that younger generations of hitmakers had picked up on what he’d been laying down.

It also quickly became clear that I had nothing to be nervous about. Meeting one’s heroes can be a dicey prospect, but Sérgio was an absolute joy to speak with — charming, funny, thoughtful, surprisingly humble, and he laughed easily and often during the course of our conversation. (He was particularly amused by my suggestion that “Crystal Illusions” was psychedelic.) He was also still clearly very much in love with his wife and muse Gracinha Leporace, the Brazilian singer who replaced Lani Hall in his group in 1971 (after the latter left Brasil ’66 to marry Herb Alpert), and who briefly appeared onscreen a couple of times during our chat to assist Sérgio with the Zoom technology. The only time he got at all heated was when the term “cover” came up — a term that he clearly felt was inadequate to describe his approach to rearranging and reimagining other people’s songs. (I’m inclined to agree with that.)

I remain immensely grateful to my editor and friend Randy Bookasta at FLOOD for giving me the assignment — he knew how much I adored so much of Sérgio’s music — and equally grateful for having had the opportunity to tell one of my musical heroes how much his work meant to me. I try not to keep cool during interviews and not fanboy out too much, but our rapport was so easy that I felt like I could slip a little compliment in at the end without things getting awkward. And now that he’s gone, I’m especially glad that I did.

[We were a few questions in when I realized that I hadn’t turned on my recorder. So his first comment here is a response to a question about forming the Bossa Rio Quintet in the early 1960s…]

I'm not a singer, I’m a pianist and an arranger. So I said, “I’m gonna put something like in the style of Art Blakey and that kind of thing — two trombones and tenor saxophone and drums.” And so the thing was very… I don't know the word, but it was the opposite of the minimalist guitar and vocal. And I loved that sound, and people did too, because it was such a different thing from the guitar/voice, singer/ composer thing. And I played all the repertoire from [Antonio Carlos] Jobim, and from other composers at the time.

So that was the sound that I came up with in those days. It was a wonderful time. We came to Carnegie Hall in ’62 for the Bossa Nova Jazz Festival. I was very well received, and I was invited to do the album with Cannonball [1963’s Cannonball’s Bossa Nova]. So, that’s the beginning.

What was it like going into the studio in the US for the first time, and working with Cannonball Adderley?

Oh, it was like, it was amazing. I was in awe, meaning like, I couldn’t believe that there was my idol, and I was working with him. He was a gentle, wonderful person, very nice, very warm, and I just couldn't believe it. I was pinching myself. Like, “I’m here working with Cannonball! It’s not possible!” [laughs] I was like, 21 years old. And so all of those things, you know… I mentioned the word “serendipity” a few times in the documentary. And I think it describes pretty much those encounters for me.