Okay, I lied.

Well, maybe I just misspoke. I really did intend for last week’s Jagged Time Lapse Christmas Party to be my last JTL post until after Christmas… but then I started thinking a lot about a holiday-themed piece that I originally wrote back in 2019 and re-ran here last year with a few tweaks. I’m very fond of it, for a number of reasons, and will probably revamp it again somewhat at some point in order to include it in the “musical memoir” I’ve been working on, which focuses my turbulent adolescence and how popular music served as my life raft during those years.

Unlike my other holiday-themed installments of JTL this year (or, say, my recent memoir chapter about discovering the joys of marijuana and Foghat Live on the same bus ride home from school), this piece isn’t particularly festive; in fact, it’s kind of a downer. But it was also originally written as a nod to the fact that Christmas can be an exceptionally hard and depressing time of year for a lot of folks — and that sometimes music (of the distinctly non-Christmas variety) can be very helpful in bringing much-needed comfort and staving off the encroaching darkness. So I’m re-posting this in empathy and solidarity with anyone who’s feeling down right now with the Christmas blues…

December is the darkest month.

This is inarguably true from a literal standpoint; according to science, which roughly half of us still believe in, these are unquestionably the shortest days of the year. But there’s a metaphorical and even metaphysical aspect to December’s darkness, as well. Sometime when I was around 11 or 12, I began to suspect that the bright, festive lights of Christmas and Hanukkah were not just lit in celebration of the holiday season, but also to keep something ominous at bay — much in the way that a campfire is lit not just for warmth, but also to ward off any fearsome creatures that may be silently lurking in the shadows.

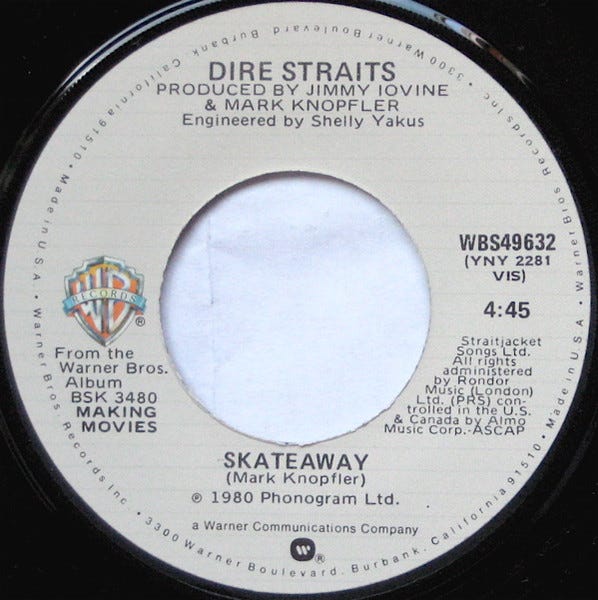

This suspicion first really took shape for me on December 3, 1979, when 11 concertgoers were trampled to death while trying to see The Who at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Coliseum. Before that infamous incident, music had always seemed pure and magical to me; I probably couldn't have articulated it as such at the time, but I essentially saw music as a transfer of positive energy from performer to listener that elevated both. (Obviously, I hadn’t learned about Altamont yet.)

The only times I had vaguely sensed that there were any darker forces embedded in or around popular music were whenever I heard “death songs” like Jody Reynolds’ “Endless Sleep” or Ray Peterson’s “Tell Laura I Love Her” on LA’s oldies station KRLA, or imagined I’d picked up an aural whiff of something spookily portentous in the songs Buddy Holly recorded shortly before his plane went down in Clear Lake, Iowa.

But that stuff was all from an era long gone; the immediacy of The Who’s concert tragedy, and the knowledge that these kids (who could have easily been me, my friends, or their older siblings) died while trying to experience what was supposed to be a joyful communal experience, seriously freaked me out. The fact that this horrific event had happened just three weeks before Christmas (“The Most Wonderful Time of the Year!”) forever disabused me of the naive notion that music or the holidays were somehow magically impervious to the awful intrusions of real life.

Still, there was so much positive and exciting stuff happening in my life in the December of ‘79, the unsettled feelings I experienced in the wake of the Cincinnati tragedy didn’t linger long. My mom, sister and I were gearing up to move from LA to Chicago at the end of the month, a prospect which was thrilling in and of itself; but on our way to the Windy City, my sister and I had also been booked to take a holiday detour to New York City, where we would spend Christmas with our dad and then-stepmother. I had been born in NYC, but — given that we’d moved to Ann Arbor when I was just a little over a year old — I had never consciously experienced the wonder of the Big Apple during the December holidays. And holy moly, did my dad ever make sure that it delivered for us.

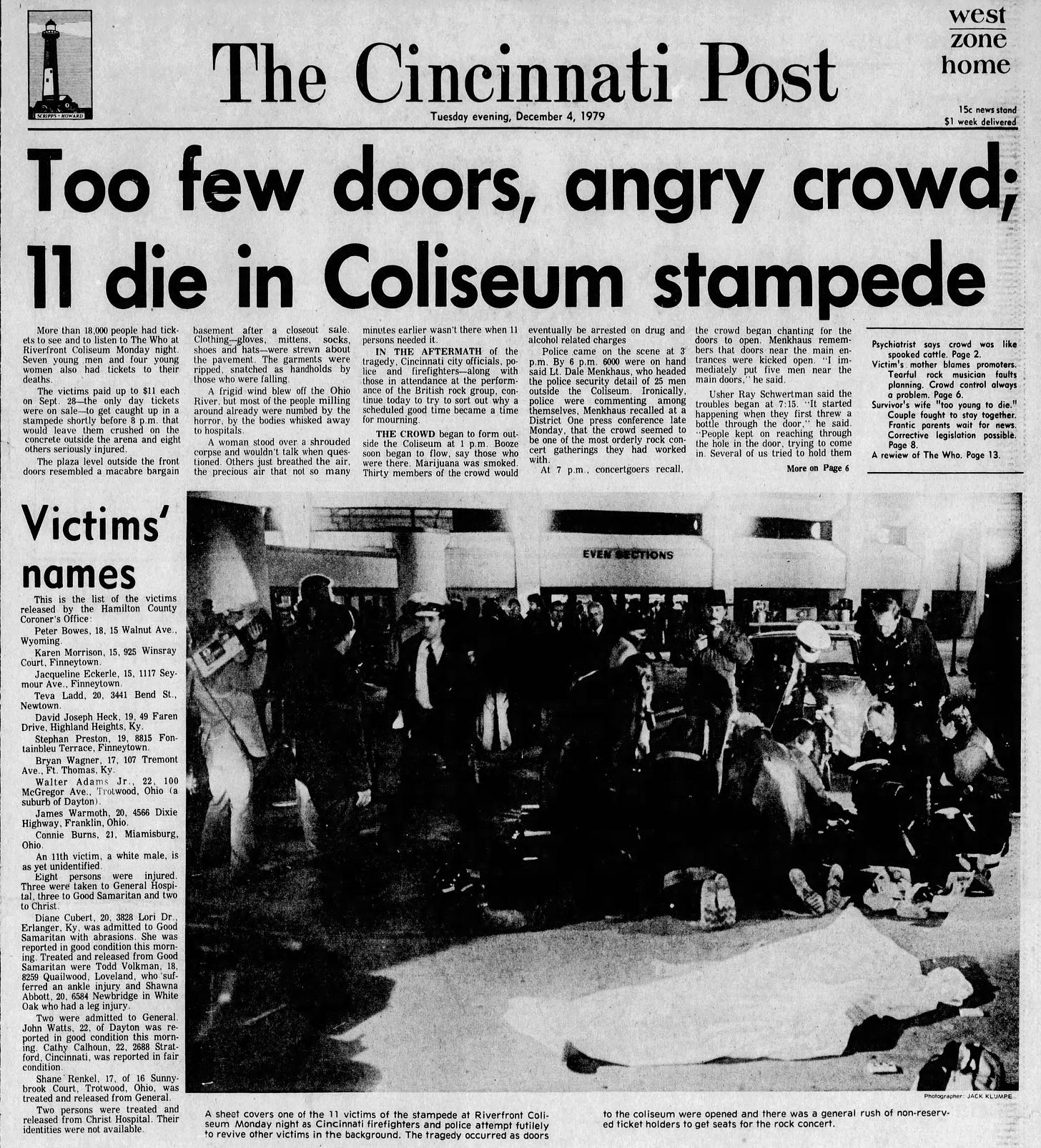

My memories of Xmas ‘79 play back like a montage of stereotypical romantic “Christmas in NYC” images — attending the Rockettes’ Christmas show at Radio City Music Hall, watching the ice skaters at the Rockefeller Center rink, buying roasted chestnuts from a vendor on Fifth Avenue, checking out the Christmas window displays at Macy’s and Lord & Taylor — mixed with even richer, more life-affirming experiences. I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Egyptian wing for the very first time, fully opened my eyes to the stunning beauty and grandeur of the city’s 1920s and 1930s architecture (Was that a Babylonian frieze atop the Fred F. French Building?!?), enjoyed the city’s wealth of incredible radio stations and record stores, and learned about Max’s Kansas City, which was located kitty-corner across Park Avenue South from my dad's apartment building.

I had read a little about punk music, and was already digging some bands classified as “new wave” — Blondie, Talking Heads, B-52s — but hadn't yet felt remotely connected to any of it. But from my nocturnal perch in the living room window of my dad's south-facing eleventh-floor loft, I could watch the local scenesters coming and going from this legendary NYC nightclub, and feel like I was somehow part of the action, even if I was way too young to actually get inside.

I’d visited NYC a few times before, but my ongoing decades-long love affair with Manhattan really began during this trip. In retrospect, it’s not too much of a stretch to say that a large part of the person I am today was forever molded by the six or seven amazing days I spent there that Christmas, and I am forever grateful for it, and to my dad for making it happen.

We went back to NYC for Christmas 1980, but this time the vibe and experience was entirely different. December’s darkness had again fallen brutally hard, this time via John Lennon’s assassination in front of the Dakota, the century-old building where he and Yoko Ono resided.

It was horrifying enough that Lennon had been killed, and that his artistic light had been cruelly snuffed out just when he was beginning to let it shine again. But the fact that it happened in the city that he’d called home for the better part of a decade, which both embraced him as one of its own and acted like it was no big fuckin’ deal that he and Yoko could occasionally be seen around town, seemed to have genuinely shaken the Big Apple to its core. (Yeah, sorry about the pun, I know...) This New York Daily News headline really sums it up: It's not just “John Lennon Slain,” but “John Lennon Slain Here”. New Yorkers took that shit personally.

I could feel the shift in NYC’s mood from the previous December almost as soon as we landed at JFK. Whereas the energy of Xmas ‘79 was the glitzy, disco-fied giddiness of a city still very much on the defiant rebound four years after President Ford had told it to drop dead, being out in NYC circa Xmas ‘80 felt like wading through a gigantic, barely-stifled sob. We made the rounds again to all the traditionally festive places, but there didn't seem to be much to actually celebrate; Ronald Reagan had been elected six weeks earlier, John Lennon was dead, and even this fourteen year-old could sense that an era was ending, and that things were about to take a serious turn for the worse.

It seemed like every place I went into that Christmas was playing John and Yoko/Plastic Ono Band's “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” on an endless loop. The song of hope now felt like a funeral dirge; each time its kiddie chorus rang out, that choked sob of the city seemed poised to spill over into a gushing rush of heartbroken tears. As I always did back then, I turned to the radio for escape, for deliverance from the gloom — though this time, with my station-changing hand perpetually poised to act in case of yet another spin of “Happy Xmas”.

There was one song in regular rotation on WPLJ that December which kind of snuck up on me — a song so low-key, I may not have even noticed it the first few times I heard it. It was “Skateaway,” a single from Making Movies, the third and latest album from Dire Straits. I had liked “Sultans of Swing” during its hit run in late 1978 and early 1979, but I wasn't exactly a Dire Straits fan; in fact, I was completely unaware at the time of the existence of Communiqué, the band's second album. “Skateaway” changed that for good.

I didn't know that the song and album had been produced by Jimmy Iovine, who'd been behind the board for several of my favorite records from the last three years (including Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ Damn the Torpedoes, and Graham Parker and the Rumour’s The Up Escalator), or that Mark Knopfler had been widely hailed as a new guitar hero. For the moment, all that mattered was “Skateway”’s slinky groove, its NYC-derived images of a rollerskating girl “slipping and a-sliding” her way through the city's traffic, and the way the song gradually built to a spiritual celebration of the enchanting lure of urban life and the transcendent power of music.

Listening to “Skateaway” on headphones now, I'm struck by what a strange beast it is. With its tossed-off shuffles and last-minute fills, Pick Withers' drumming is wonderfully idiosyncratic in a way rock drummers on major labels haven’t been allowed to be for decades, but the echo placed on his kit sounds completely unnecessary (and at times maybe even a little “off”). Aside from Knopfler's soaring single-note accents during the chorus (and his volume swells during the extended outro), Springsteen keyboardist Roy Bittan seems to carry most of the melodic weight of the song with his liquid playing, while the admittedly impressive chicken-picking that Knopfler performs during the verses sometimes almost seems to have wandered in from the wrong song. Vocally, Knopfler seems at first like he’s laconically talk-singing a la Bob Dylan or J.J. Cale, but upon closer listens it becomes clear how much effort (and variations in tone, attitude and energy) he's putting into his performance.

But heard together through the half-dollar-sized mono speaker of my stepmother's radio/cassette player, all these weirdly disparate elements cohered into something spellbinding, evocative and irresistibly transportive — something which allowed allowed me to glimpse a little light amid the darkness I experienced that December. Though obviously filled with summer-spawned imagery (nobody’s foolhardy enough to rollerskate through the ice and slush of Manhattan streets in December), “Skateaway” has thus always felt like a Christmas song to me.

Indeed, “Skateaway” has been in my head again a lot lately, even soundtracking some of my dreams. I suspect it has something to do with this time of year, and the knowledge that so many of my friends — and so many people in general — are badly struggling right now. So many people I know are wondering if it's all going to be downhill from here with their own lives, this country, or our civilization in general. Some are wondering if they'll ever work again; others if they or certain loved ones will even be alive to see next Christmas. I know that those kind of questions, never exactly easy to bear, become especially heavy during the darkness of December, and I certainly have no answers.

All I have is a Christmas wish, which is that they (and you) will be able to find some comfort and joy amid the darkness — even if it's just in the form of a song that, for a few minutes at least, will let you skate away. That’s all.

When I was 10, I was convinced this was the greatest album ever made. Thanks for making me feel 10 again for a couple minutes, Dan. Happy holidays.

Fascinating band & dude, loads of great work. It took me a while to get on to the rest of the studio albums after their first, which to me will always be the best but hell, the lyric, "Just the way that her hair fell down around her face" from "Lady Writer" has always slayed me - that's the only cut from Communiqué that's in my DS song list, along with the far better version of "Once Upon a Time in the West" off of "Alchemy". Same goes for "Skateaway" - good on Making Movies, but "Tunnel of Love," "Romeo & Juliet,"Expresso Love" & "Solid Rock" much better on "Alchemy". Again same, "Telegraph Road" & "Love Over Gold" much better live than on "Making Movies." I do like "Private Investigations" off of Making Movies. Point being, once I consolidated the cherry picks along with the entirety of the debut, I listen to a lot more DS than I did when I wasn't paying enough attention, plus it was rough when "Brothers in Arms" came out and oversaturated us on mtv, etc. I do include "So Far Away," "Man's too Strong" and "Walk of Life" from that one.