The music gods recently smiled upon me, their favor taking the form of a very reasonably priced reel-to-reel tape of the wonderful Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra.

I’ve written about Jamal here before, reflecting on how the legendary jazz pianist’s blockbuster 1958 album But Not For Me was the record that caused (or maybe enabled) me to drop my prejudiced misconceptions of jazz during the early nineties, and sent me on a journey into the jazz universe that continues to this day.

But Not For Me had a pretty profound effect on Jamal’s life, as well; selling over 50,000 copies in its first year of release — a massive amount for a jazz record in those days — the album transformed him into an international star earning several thousands of dollars per week. He channeled some of that money into buying a 16-room, six-bath mansion in Chicago’s Hyde Park, as well as a four-story office building at 1321 S. Michigan Avenue, less than a mile up the road from where the offices of Chess Records (whose subsidiaries included Argo, Jamal’s label) were located. And on that building’s ground floor, he opened a nightclub: Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra.

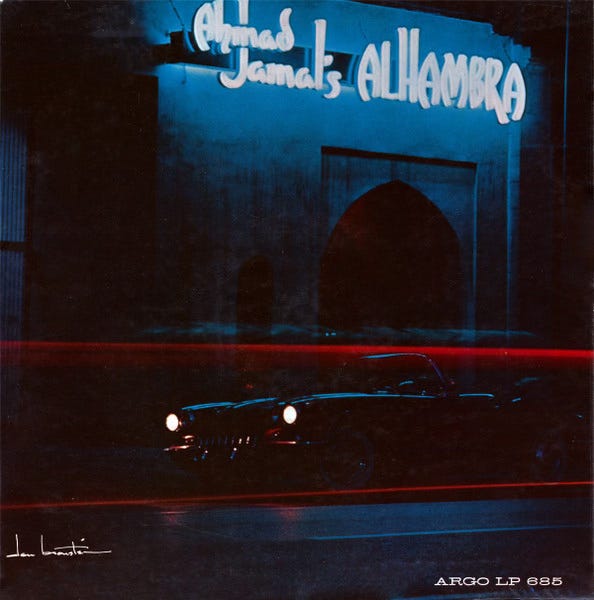

I’ve never seen any photos of the Alhambra, save for the moody exterior shot that graces the cover of the album of the same name — an image whose intriguing combination of exotica and urban cool meshes beautifully with the album’s music. Recorded live at the nightclub in June 1961, shortly after the establishment opened, Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra finds the pianist, bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernel Fournier (the same lineup that recorded But Not For Me) grooving gorgeously through ten standards including Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “We Kiss in a Shadow,” Claude Thornhill’s “Snowfall” (a mainstay of my Christmas mixes) and Ann Ronell’s “Willow Weep for Me”.

The vibe is playful without sacrificing any of Jamal’s intrinsic elegance, and there’s enough space in the music to drive the sports car on the cover through. Cut for cut, note for note, I already kinda preferred Alhambra to But Not For Me — but hearing it on reel to reel has been an absolute revelation, making me feel like I’m actually sitting onstage at the Alhambra; Crosby’s upright bass sounds so fat and present, I can practically picture the instrument’s woodgrain. Listening to Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra again — combined with a Facebook conversation about it with my friend Don Baker —has also sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole, curious to find out more about the nightclub and its eventual fate.

Again, it’s too bad that there don’t seem to be any photos of the club floating around on the internet, because the few contemporaneous accounts of the place that I’ve read describe it as a quite the opulent showcase. In the March 19, 1961 edition of the Chicago Tribune, nightlife columnist Will Leonard offered a preview of the still-in-progress venue, calling it an “exotic cafe” with a “Islamic-Sarcenic motif,” with an entrance “modeled after the Court of Gold in the architectural classic at Granada, and whose main room is inspired by the Court of Lions.”

Leonard didn’t interview Jamal for the item, but rather spoke with a Basque artist named Frederic de Arechaga, who had apparently designed the interior and was busy hand-gluing its decorative mosaics together when the Tribune writer stopped in for a tour. Several years later, de Arechaga would found the Sabaean Religious Order, declaring himself its “Pontifus Maximus”. The religion, which incorporated elements of Egyptian, Babylonian, Mesopotamian and Sumerian mythology, was headquartered in the late sixties and early seventies at 2447 N. Halsted Street in Chicago, the same address where de Arechaga’s mother had run an occult shop known as El Sabarum.

It’s unclear whether or not Jamal, who was born Frederick Russell Jones before converting to Islam in 1950, was at all aware of (or bothered by) de Arechaga’s occult background. In any case, Jamal’s Muslim faith — as well as his recent travels in Africa and the Middle East — almost certainly influenced his fateful decision to make the Alhambra an alcohol-free zone.

An ardent teetotaler, Jamal confidently explained this decision to a reporter from DownBeat magazine. “I don’t think it will be successful,” he said of his nightclub. “I know it will be successful, because I know what the public wants and because the Alhambra is more than just a moneymaker; it is a contribution — one of the finest restaurants in the world. Any room can go out of business because of bad management… We know we can make it, and the only way is not to sell alcoholic beverages. The best beverages are those nonalcoholic in content. We shall provide the finest in entertainment.”

Reading Jamal’s words over sixty years later, at a time when it’s difficult enough for a club or restaurant to get by without the high profit margins that alcohol sales provide, one can’t help but brace for the inevitable train wreck. But back in the days of the three-martini lunch, a nightclub without liquor must have seemed like a completely bizarre business model. And yet, Jamal was apparently quite certain it would work…

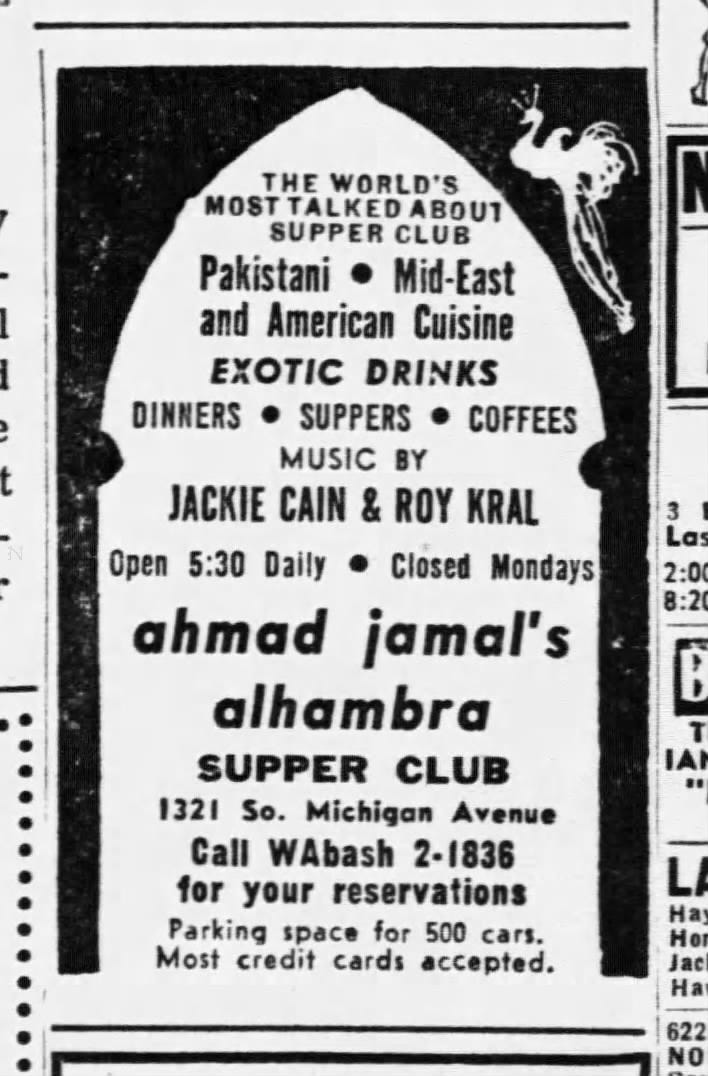

Lack of booze aside, however, it sounds like the Alhambra was quite a fine place to spend an evening. A June 25, 1961 clip from the Tribune mentions that, in addition to its substantial visual charms, the new nightclub also features Pakistani/Indian and Middle Eastern cuisine on its menu — fare which must have seemed quite exotic to most midwestern jazz club denizens circa 1961. Plus, having the opportunity to enjoy three sets a night from the mellifluous and soothing Ahmad Jamal Trio would have been wonderful, whether or not you were able to surreptitiously spike your mint cooler with bourbon.

Alas, for whatever reason, “the finest in entertainment” that Jamal promised never really seemed to materialize on the Alhambra’s bandstand. Aside from Jamal’s own trio, the only “big names” to appear at the nightclub with any regularity were Jackie Cain and Roy Kral, a.k.a. jazz vocal duo Jackie & Roy.

Whether due to the no-alcohol policy, a lack of big bookings on the calendar, its just-south-of-the-Loop location, or all of the above, it was all over for the nightclub after barely seven months. “Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra has folded its tent like the Arab and just as silently stolen away,” wrote Will Leonard in the December 3, 1961 edition of the Tribune, putting the blame squarely on the establishment’s booze-free bar.

The club’s demise was just one in a series of bummers to beset Jamal in 1961 and 1962. Despite receiving rave reviews upon its release in September 1961, Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra — perhaps just a little too similar to But Not For Me and the albums that immediately followed it — failed to make the charts. Then in May 1962, DownBeat reported that his wife had filed for divorce on grounds of desertion; Jamal was simultaneously suing Chicago’s Johnson Publications for a million bucks, claiming Jet magazine had libeled him by portraying him as financially irresponsible, and that the magazine had cited said irresponsibility as a major factor in the breakup of his marriage.

By this point, Jamal had also broken up his trio with Crosby and Fournier, though he claimed it was only a “temporary disbandment” while he attended to business matters, and that the three musicians would reconvene in the near future. But Crosby — who then briefly joined up with George Shearing — took that possibility out of the equation that August by dying of a heart attack at the age of 43. 1962’s Ahmad Jamal at the Blackhawk, recorded in November 1961, would sadly be the last release to feature the classic trio in action.

But for a few months in the summer and fall of 1961, Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra was the shining jewel of Chicago’s jazz scene. The club and the building that housed it may be long gone, but at least we still have one fantastic album to remember it by.

Even if it caused his nightclub to fold, Jamal proved he was a true Muslim....

Loved this one, Dan