If there’s one thing I never tire of reading, it’s first-person accounts of what it was like to live in New York City — especially the borough of Manhattan — at various points throughout the 20th century.

Part of this is surely due to the intense personal connection I feel with Manhattan. Having been born on the Upper West Side and — though I spent the bulk of my childhood elsewhere — having been raised on such pop cultural touchstones as MAD magazine, The Odd Couple, Kojak and the folk-rock hits of Bob Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel, I can’t remember a time when I didn’t think that NYC was anything but the coolest and most interesting place in America, if not the world.

But it also has to do with my endless fascination with the city’s constant reinvention of itself over the course of the 20th century, and the myriad ways its residents experienced and were shaped by it. Joseph Mitchell and A.J. Liebling wrote extensively and vividly on this very subject for the New Yorker, especially during the 1930s and 40s; and while none of the folks they profiled are with us any longer, I love that I can still visit some of the spots celebrated in their work — like, say, McSorley’s Pub — and commune with the very-present ghosts of a NYC that no longer really exists.

That said, when I think of “a NYC that no longer really exists,” what I really miss is not the colorful demimonde of two-bit pugilists, low-stakes chiselers and professional drunks that Liebling and Mitchell described, but the down-at-its-heels Big Apple of the 1970s and 80s, a city that was still empty and affordable enough for artists to live and create in. That NYC I remember well and fondly, even if my experiences of it — like sitting late at night in the living room window of my dad’s loft on 18th Street circa 1979 and watching local scenesters loitering outside of Max’s Kansas City — were more observational than actively involved. Even during the second half of the eighties, when I was regularly taking the Metro North down from Poughkeepsie to see bands play at CBGB, The Ritz, the original Knitting Factory, etc., I was never “of” the NYC music scene; I got close enough to dip my toe in and take its temperature, but was always well aware that I was really just seeing its shimmering surface.

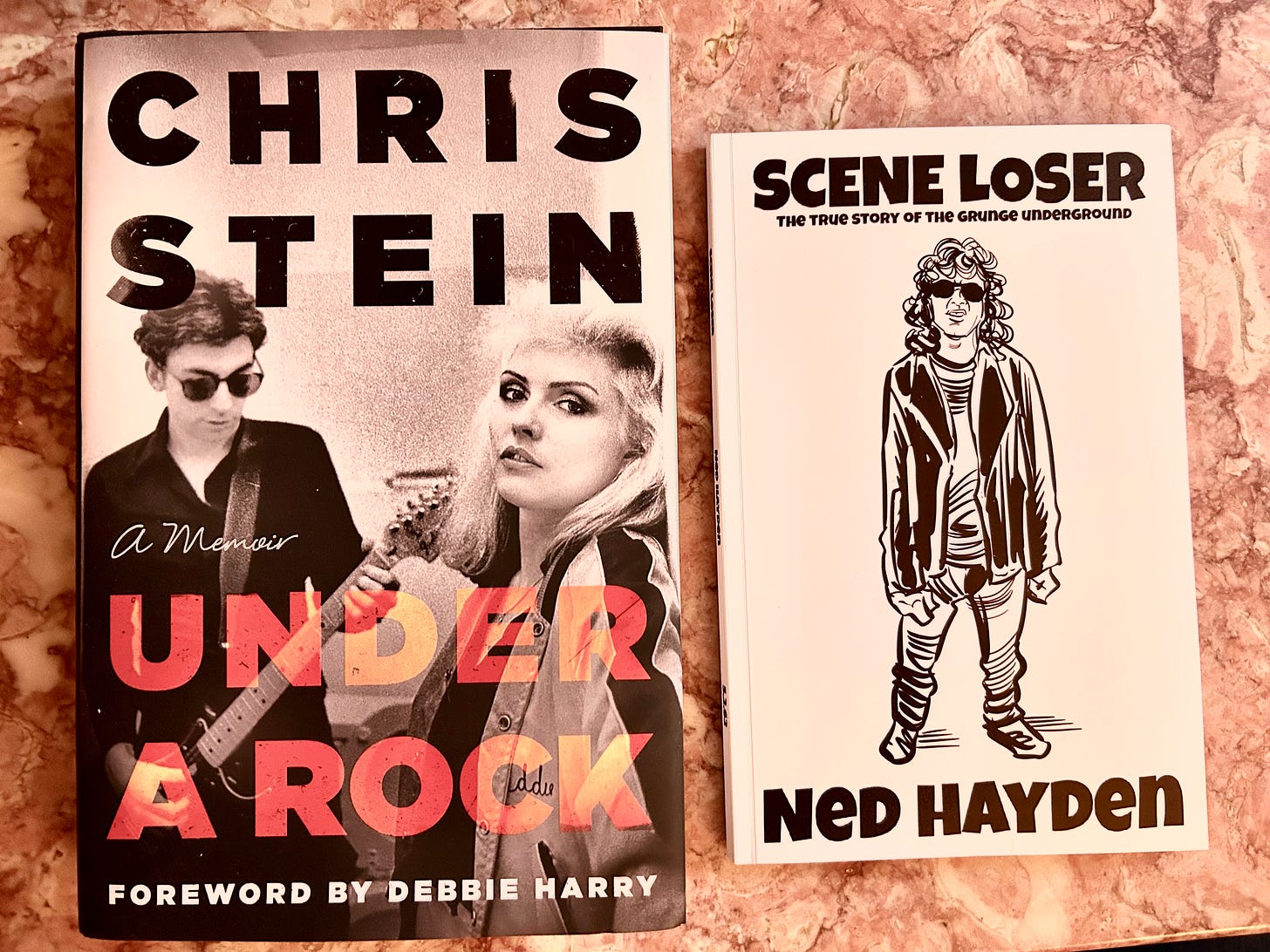

Which is why Chris Stein’s Under a Rock: A Memoir and Ned Hayden’s Scene Loser: The True Story of the Grunge Underground are total catnip to me. Both memoirs revolve around NYC music scenes during eras that I actually experienced (or at least caught a tail-end whiff of), while filling in all kinds of vivid details about what it was actually like to be living and playing in Manhattan in the days where it was no big deal to run into Jimi Hendrix on the streets of the West Village (Stein) or see Johnny Ramone in line at the Cooper Square post office (Hayden). I got completely lost in both books, and had immense difficulty putting either of them down.

Stein’s book is more of a straightforward autobiography, one that begins with the Blondie guitarist and co-leader’s early childhood in a now-unrecognizably “rustic” Brooklyn where many of the side streets are still unpaved and a handful of trolley lines still function. An only child given extensive encouragement and leeway by his artist mother, Stein is initially obsessed with films (especially horror flicks) before The Ventures, Beatles and Rolling Stones lure him into rock n’ roll, which soundtracks and inspires his pursuit of a more bohemian existence.

I’ve been a Blondie fan since the spring of 1979, when their then-new single “One Way or Another” blasted out of my clock radio and into my adolescent consciousness. (I’d already heard “Heart of Glass,” but didn’t really know what to make of it at the time.) I almost immediately fell in love with Debbie Harry — who didn’t in those days? — but as I learned more about the band I became equally fascinated (well, almost equally) with Chris Stein and his relationship with Harry.

For one thing, the fact that the preeminent rock goddess of the era was completely in love with this kinda nerdy, unconventionally attractive Jewish guy was immensely encouraging to my awkward young-teen self; for another, every interview I read with them made them sound like really funny and interesting people who had a genuine blast creating and collaborating together. I’d listen to a song like “Picture This” and imagine what it must be like to wake up each morning in 1970s New York City with the love of your life, and then spend the day and night doing cool New York City stuff together. That seemed like the most romantic thing in the world to me.

Stein’s recollections in Under a Rock don’t do much to dissuade me from my original assessment; along with his eventful teenage years (which include his high school band getting tapped in April 1967 as a last-minute opener for The Velvet Underground at The Gymnasium, a short-lived venue on the Upper East Side), the richest and most entertaining material in Stein’s memoir involves his life with Harry in the 1970s, when the pair are living on the Bowery, exploring various facets of NYC underground culture, and regularly crossing paths with the likes of The Ramones and Television at CBGB and elsewhere while slowly getting Blondie’s music and concept together.

Unfortunately, Blondie’s sudden success with Parallel Lines takes them away from their NYC base for increasingly long and exhausting periods of time, creating personal strains (and worsening the Class A drug addictions) that eventually unravel the band, their romance and Stein’s health — though Stein and Harry happily remain close friends and creative partners to this day.

Stein tells his and the band’s stories with a dryly amusing wit; his low-key humor only (and perhaps understandably) gives out at the book’s end, when he’s grieving for his 19 year-old daughter — who dies in 2023 of an accidental drug overdose — and for the high hopes he says he no longer holds out for humanity. In all, Under a Rock is an absorbing, thought-provoking and occasionally quite moving collection of Stein’s memories, some of which made me wish I’d been old enough to really enjoy the Village and downtown NYC of the sixties, seventies and early eighties, and some of which made me really glad I wasn’t.

“It’s always the best and worst of times,” Stein concludes; “those guys back then didn’t have any kind of exclusive.”

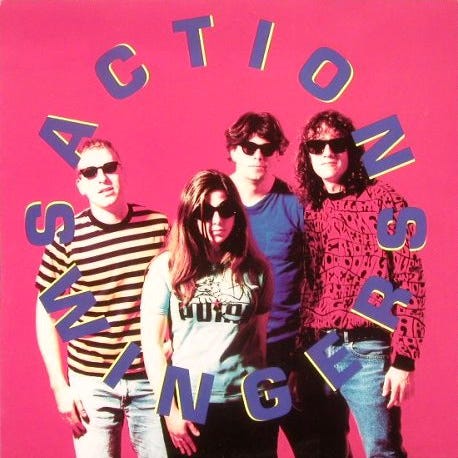

While Ned Hayden’s Scene Loser is also rooted in the East Village and its environs, and features cameos from many of the same characters that appear in Under a Rock, it’s a much different scene that Hayden captures, a much different NYC, and ultimately a much different book. Hayden, who led The Nightmares (they of the immortal single “Baseball Altamont”) and Action Swingers, barely mentions his life before or after those bands, choosing instead to concentrate on his acerbic first-hand recollections of the alternative rock explosion of the late eighties and early nineties, as well as the cultural fallout that resulted from it.

After a brief flashback to 1985, when Hayden takes some psychedelic mushrooms at a Green River/U-Men show at Maxwell’s in Hoboken — a gig that foreshadows the coming Seattle-led alt-rock explosion — the book essentially opens in late 1987, with Hayden applying for a job at the CBGB Record Canteen, the record shop and cafe that CB’s owner Hilly Kristal has opened next door to his legendary venue. At this point, it’s been nearly a decade since Blondie and most of the original NYC punk bands last performed at CB’s, and the club is mostly getting by on its historic reputation while booking bands from just about every rock-related genre; Hayden’s first day on the job finds him pouring a cup of coffee for Axl Rose, who’s there to play an acoustic set at the Canteen with a teetering-on-the-edge-of-stardom Guns N’ Roses.

The East Village where Hayden lives and works bears plenty of superficial similarities to the one Stein and Harry called home in the mid-seventies, and there’s still a vibrant community of musicians and artists in the vicinity. But it won’t remain this way for long — real estate developers are moving in and (with the help of the city and the NYPD) trying to muscle the freaks out, their gentrification efforts sparking the Tompkins Square Riots of August 1988. The East Village underground music scene, already a prickly and volatile grab-bag of bands and personalities, is likewise about to see what happens when the wheels of commerce roll into the picture…

I’ll confess here that I never listened to Action Swingers until well after they broke up in the mid-nineties. Having gone to college just two hours up the Hudson from Manhattan between 1985 and 1989, and serving as a DJ on my college radio station for most of that time, I’d already been inundated by the likes of such contemporary NYC underground bands as Sonic Youth, Live Skull, Pussy Galore and Royal Trux. Post-punk noise-rock wasn’t my thing at all, and neither was what I saw at the time as the cooler-than-thou posing of those bands and their fans; so whenever a new band emerged with some connection to that scene — like Action Swingers, whose membership included former Pussy Galore members Julie Cafritz and Bob Bert — I actively ignored them.

And anyway, by the late eighties I was far more interested in the new music that was coming out of Seattle, stuff by bands like Mudhoney and Screaming Trees that was noisy and confrontational while also serving up a hard-grooving twist on the raucous sixties sounds that I was obsessed with — Stooges, MC5, Blue Cheer, Sonics, etc. As it turns out, that was also pretty much where Hayden was coming from with Action Swingers, albeit with some early Black Flag thrown in for extra obnoxiousness. While Nirvana’s 1991 hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is often cited as a watershed moment in the “grunge” revolution, Hayden quite correctly points to Mudhoney’s 1988 debut single “Touch Me I’m Sick” as the record that really kicked the whole thing off:

“Touch Me I’m Sick” totally spoke my language, fuzzed out guitars, screaming vocals and a hook the size of Mount Rainier. It was the culmination of everything the underground scene of my generation was into at the time in America from the name of the band, derived from the trashy 1965 Russ Meyer cult movie, to the cheap pawn shop guitars and vintage fuzz pedals to the Iggy Pop meets Blue Cheer title and riff. They had long hair and wore flannel shirts over T-shirts, jeans and sneakers. They sold like crazy as word spread and set off a musical and cultural revolution that would change the course of history.

Working as a record buyer for the CBGB Record Canteen and as a sales rep for Caroline Records, Hayden has a front-row seat for this cultural revolution, while also getting swept up in it both as a musician and as the proprietor of the indie imprint Primo Scree.

But while everyone in the New York scene seems to embrace the Seattle bands, they don’t extend that same degree of support and generosity towards each other, and things get even chillier and more cutthroat once the major labels and well-funded indies start swarming. Scene Loser paints an enormously amusing (if also cringe-worthy) picture of a music scene in which alliances are constantly shifting, everyone is jockeying for position while talking shit behind each other’s backs, and one wrong word in a fanzine column or interview can transform a friendship into a decades-long grudge. (As someone who was playing in a band on the equally bitchy Chicago alt-rock music scene at the same time the events in Scene Loser unfold, I have to say that Hayden’s account rings completely and hilariously true.)

Still, while Hayden indulges in some copious shit-talking of his own in Scene Loser — Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon are just a few of the folks he gleefully bashes — he doesn’t spare himself at all, ruefully remarking on his own overly-inebriated shenanigans, ill-advised rants and poor decision making. But hey, when your long-held dream of giving the world a rock n’ roll kick in the ass suddenly starts to come true, it’s not necessarily going to bring out the best in you…

And Hayden’s dream does indeed come true, at least during that brief window in the early spring of 1992 when Nirvana-mania stimulates a sudden hunger in Great Britain for any American band with rough guitars and indie cred, and Action Swingers’ self-titled debut album is catapulted into the UK indie Top 20 right as the original lineup of the band is falling apart. A hastily-assembled new lineup embarks on a triumphant British tour that the band caps by recording a live-in-the-studio session for the legendary DJ John Peel’s BBC Radio 1 show. His first night back in NYC, Hayden orders takeout from his favorite neighborhood Mexican joint, only to get an angry earful from a bartender who has taken serious umbrage over Hayden’s recent interview in the UK music mag Melody Maker:

The guy launched into a diatribe about who the hell did I think I was and how the British press acted like I invented punk rock. He was obviously a very bitter and frustrated musician. With a Melody Maker subscription. I said I didn’t know what to tell him and I really just wanted to get my food and get out of there. Just then they brought up my bag which he shoved at me with a sneer. It was great to be home.

Scene Loser only runs about a hundred pages, but it seems like almost every page contains at least one memorable, laugh-out-loud story. Hayden has a real knack not just for teleporting the reader back to particular moments in time, but also for succinctly capturing the realities and absurdities of what it was like to be an underground musician in New York in the late eighties and early nineties.

Scene Loser also contains a veritable who’s who of punk and indie musicians, with one notable personage after another popping up in (or stumbling through) Hayden’s stories. Go to any page at random, and you’ll find brief but hysterical tales of Johnny Thunders bitching about being overcharged for a guitar because he’s famous, Dinosaur Jr.’s J. Mascis falling asleep in Thurston Moore’s living room while Thurston’s trying to make everyone watch a VHS compilation of his favorite prog-rock moments, or Screaming Tree’s singer Mark Lanegan and Mudhoney bassist Matt Lukin making out with each other on the streets of New York. “It wasn’t the first time I had seen two dudes making out,” Hayden drolly notes. “Just not two dudes as straight as them.”

As entertaining as it is to read about, the life Hayden details in Scene Loser clearly becomes increasingly exhausting, frustrating and dispiriting. By the time he decides to heed Ian Hunter’s wise words about rock n’ roll being a loser’s game, you can’t help but applaud his decision to move to the suburbs and start a family. After all, he shot his shot, made his mark, influenced some other bands in the process, and got out alive — and there are quite a few folks in this book who weren’t so lucky.

In any case, Scene Loser is a ripping read, especially if early nineties underground/alternative rock is your cup of meat. Buy a copy of the book — which features awesome cover art courtesy of my enormously talented friend Brian Walsby — directly from Ned AT THIS LINK. You’ll be damn glad you did.

Q. Is it “incest” if both father and son were/are in love with D. Harry at the same time?

A.

(1) Not if they don’t know it

(2) Not if they only fantasize about

her

(3) Not if she doesn’t know it

(4) Not if she doesn’t give a shit

(5) All of the above.

🤷🏽❤️

Very informative, two more books for the list. I'm also fascinated by all the NYC scenes and only so very slightly dipped a baby toe in while crashing at my negative' girlfriend's acting teacher mother's loft apartment adjacent to Columbus Circle. No interest in anything but touristy daytime stuff, but I would sit at the window looking out at night when they were asleep wondering what it was really like out there. Loved Mark Arm's stint in the DTK/MC5.