I spent the summer of 1988 living on a severely limited budget.

I was between my junior and senior years of college, and I’d followed my then-girlfriend to Providence, Rhode Island, where she was attending a summer program at RISD. One of my best friends was attending Brown at the time, and he hooked us up with a room in the large second-floor apartment shared by some of his friends. We paid maybe $100 a month for it, plus our share of the utilities; but even so, things were tight. My gf wasn’t working, and the only summer job I was able to find on short notice was as a line cook at a Tex-Mex restaurant on Thayer Street, making maybe a buck over minimum wage.

I was trying to sock away as much cash as I could that summer for the expenses I knew I would accrue once I got back to college that fall, so there wasn’t much disposable income to play around with. As such, my diet that summer mostly consisted of whatever free food I could cadge during my shifts at the restaurant, and ramen or macaroni and cheese (occasionally with chunks of hot dogs if I was feeling fancy) at home. And cheap beer and weed, of course. Some sacrifices are simply non-negotiable when you’re 22.

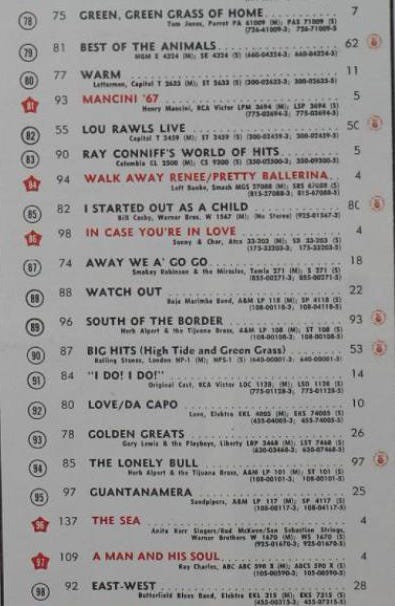

All of which meant that my record-shopping budget was fairly non-existent. I think I spent less than $20 on vinyl that entire summer — getting my fix mostly at yard sales and thrift shops (this was the summer I went HAM on Herb Alpert and the TJB), though one of the record stores near the Brown campus (I forget its name) also came through for me a few times. Among the fine albums I fished out of its surprisingly well-stocked 99-cent bin were near-mint used copies of Redd Kross’s Neurotica, The Go-Go’s Vacation, The Undertones’ brilliant self-titled first album (which I’d actually been in search of for nearly five years at that point)… as well as a worn but still quite acceptable original pressing of Love’s Da Capo.

I was already a huge Love fan at this point. I’d fallen hard for Forever Changes in the fall of ‘86, and added both their self-titled first album and Rhino’s Best of Love compilation to my collection soon after. The works of Arthur Lee and Co. had fallen pretty heavily into obscurity by this point, so I was inclined to be particularly evangelical on the subject — how come everyone I knew seemed to know who the Velvet Underground were, but the name Love just triggered a confused shrug?

So while I was pleasantly surprised to find Da Capo — a record I’d heard of but had never actually seen before — in the cheapo bin, it didn’t surprise me at all that it had been discarded there along with a mint copy of Vanilla Fudge’s The Beat Goes On. (Which I also took home that day, only to learn that it was maybe the worst rock record made in the entire 1960s. Even priced at 99 cents, I felt ripped off.)

Within the next 12 months, I would find original pressings of Love albums Four Sail, Out Here and False Start at used record stores in New Paltz, Northampton and Chicago, respectively, none of which set me back more than five or six bucks. Very few people seemed to remember or care about Love in those days.

I sure cared, though, and was thus absolutely delighted to get my hands on Da Capo, even though I already had five of the album’s seven songs on Best of Love. The aesthetics alone were worth the price of admission; the band’s moody, multi-racial lineup — now expanded to seven members with flautist/saxophonist Tjay Cantrell and new drummer Michael Stuart — looked absolutely badass on the record’s already-framed front cover, which I figured I could always just hang on my wall if the record wasn’t playable.

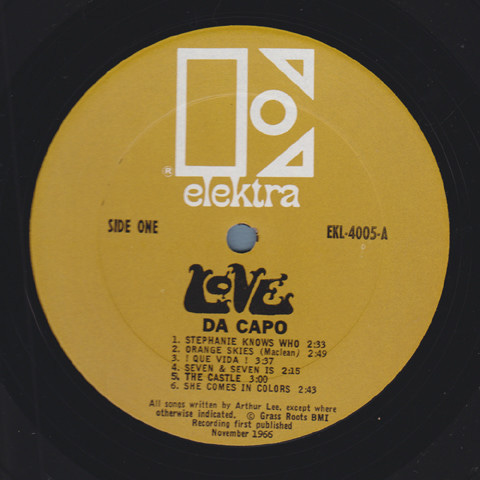

But aside from a few pops and clicks and a little surface noice, this copy actually sounded pretty decent, and it was a real thrill for me to finally hear the six songs on Side One in their intended order, instead of scattered willy-nilly across two sides of Best of Love. It made me think of how incredible it must have been to hear this record in January 1967, when it was first released. Not only were these songs remarkably richer, weirder and more complex than anything on the band’s folk-rock-y first album (which had been released less than a year earlier), but they sounded nothing like anyone else was doing at the time. Listening to the wild-eyed jazz-rock time-shifts of “Stephanie Knows Who” followed by the lilting reveries of the Bryan MacLean-penned “Orange Skies,” the playful Latin groove of “¡Que Vida!” and the raging proto-punk assault of “Seven & Seven Is” was a serious mind-blower even in 1988, to say nothing of 1967. I can’t think of another rock band that was showing this kind of range at this point in history, much less combining it with this potent level of songwriting ability.

Arthur Lee had seriously upped both his vocal and lyrical games since the first Love album; his words here were far more acerbic, witty and evocatively poetic than before, and he’d perfected his ability to croon like a menacing, LSD-scrambled Johnny Mathis. “She Comes In Colors,” the pun-strewn, flute-filigreed psychedelic love ballad which closed Side One of Da Capo, beautifully showcased these attributes as well. These five songs were all, in retrospect, quite clearly necessary stepping stones to the creation of the landmark Forever Changes, which would be recorded later that year. So too was “The Castle,” one of the two Da Capo songs I hadn’t heard before.

A mysterious three-minute poem with only seven lines of lyrics and at least as many musical movements, “The Castle” at first felt to me like some gratuitously complex filler in search of a song, but it gradually became one of my favorite tracks on an album side already packed to the gills with gold. For one thing, “Here’s my baggage/Hand me my staff” is one of the great fancy-man opening lines of all time, predating “Hand me down my walking cane/Hand me down my hat” from The Spinners’ “Rubberband Man” by a solid decade. For another, what initially comes off as a willfully eccentric arrangement reveals itself after a few listens to be a musical painting that wouldn’t seem at all out of place on one of Ennio Morricone’s mid-’60s soundtracks. Again, name me another band back then that had this kind of range…

In other words, Side One of Da Capo is absolute perfection… so perfect, in fact, that I was recently moved to spend over 30 times what I’d paid for my original copy on Rhino Records’ new limited-edition red-vinyl mono reissue of the album. (More on that in a second.) The fact that I would willingly dole out that kind of dosh for an album whose second side is an irredeemable hunk of shit pretty much speaks to the jaw-dropping brilliance of the album’s first six songs right there.

So yeah, let’s talk about that second side. Da Capo’s seventh song, the 18:57-long “Revelation,” covers the entirety of Side Two. I approached this cut with trepidation when I first brought the album home, figuring that both its title and length promised a pretentious and meandering cosmic journey. The track’s opening flurry of harpsichord notes briefly got my hopes up for something cool — I mean, who doesn’t love a good harpsichord flurry? — but the bluesy shuffle that immediately followed quickly doused them. A non-blues band kicking into a bluesy shuffle is always a bad sign; and indeed, the smell of hot sewage began to emanate from the speakers as the track boogied onward.

I kept trying to find something to like about “Revelation,” but Arthur’s aggressively awful lyrics (“When you’re in my bed/Baby, I feel so good/Till you give me a little head”), the perfunctory guitar, harmonica, saxophone and drum solos, and the track’s monochromatic plod were all so far below the band’s typical standard of excellence that the whole track came off like an intentionally unpleasant joke. After the sheer magic of Side One, hearing “Revelation” was like chasing a sumptuous six-course dinner with a bite of a well-worn urinal cake.

As Love lead guitarist Johnny Echols has explained numerous times — including recently on Mike Stax’s fantastic Ugly Things podcast — “Revelation” had begun life as a set-long jam called “John Lee Hooker,” which could go in any number of directions on any given night, and which was the sort of thing that kept the crowd dancing at Bido Lito’s, the Hollywood club where Love were a popular draw. The band apparently recorded a 45 minute version in the studio, which Da Capo producer Paul Rothchild then edited down to nearly 19.

Echols claims that the jam made far more sense when heard in its entirety; but if what made it into the final mix was what Rothchild thought was the “good stuff,” it’s hard to imagine that the unexpurgated version would have been any easier to stomach. In any case, the band was under the gun to complete the album, and a single, side-filling jam seemed like the obvious solution at the time. Arthur himself later referred to “Revelation” as “the worst fucking song I’ve ever done in my life” — and while I know from personal experience that he liked to talk a lot of shit in interviews (and while Out Here’s “Doggone” is certainly a close contender for the Most Egregious Waste of Space on a Love Album award), I absolutely have to agree with him here. I can’t think of another album where one side is so overwhelmingly superior to the other.

Still, enough people have defended “Revelation” to me over the years — or at least shrugged, “C’mon, it’s not that bad” — that I’ve wound up going back to it once a decade or so, just to see if there’s something cool lurking within its vast expanse that I’ve somehow missed or failed to get my ears around. Rhino’s new vinyl reissue of the Da Capo presented me with a chance to give it yet another go; the company’s recent vinyl reissues of Forever Changes and Four Sail sounded so wonderful that I couldn’t resist to the chance to hear this one as well. And, for the most part, it’s great — the mono mix is clear, punchy and powerful, and really does sonic justice to the songs on Side One. With one unfortunate exception.

Somehow, the usually rigorous quality control folks over at Rhino failed to notice that the first bar of “Stephanie Knows Who” is missing. Hearing the track burst in with the band already in mid-groove reminds me of back when I used to hit “Record” on the cassette deck just a hair late while making a mixtape, causing the opening few notes of the track to disappear or fade in upon playback. It was an easy mistake to make — but then again, no one was paying me for my mixtape prowess at the time, and no one was forking over $29.98 plus tax and shipping for my TDK-90s.

As good as the rest of Side One sounds, this opening sloppiness — which is quite clearly an issue with the pressing, rather than a defect in my copy — casts a serious pall over the rest of the reissue for me. I went ahead and asked the Rhino Store for a refund, which they graciously granted. I mean, it’s not like I have a ton of money to spend on records these days, either; and if I’m gonna buy a record just for Side One, I don’t think it’s too much to want a Side One that’s completely intact.

(This version also includes a red vinyl repressing of the “7 & 7 Is” b/w “No. Fourteen” single, which sounds great — but I already have an original copy of that 45, so its inclusion here wasn’t a major factor in my purchase.)

As for Side Two, I figured I might as well give it another spin before I pack the record up to ship it back to the folks at Rhino. And… yeah, it’s still awful, and is still made all the more maddening by the top-notch tuneage on the album’s other side.

Check you out in another ten years or so, “Revelation” — maybe I’ll be hip enough by then to finally appreciate you. Until then, Da Capo will continue to reign supreme for me as the greatest half-album ever made.

Ok. I just listened to four minutes and three seconds of “Revelation” and got bored so I put on “Up in her Room” by The Seeds, because that, for me, accomplished what Love set out to do.

I prefer to play LPs front to back, as I'm a freak who logs every album listen. However, Da Capo is a Side 1 and done record. Lately I've been obsessed with Four Sail. What a record. Love rocks! Great reading this this morning.