Dave Davies: "Glimpses of This Almost Surreal World"

Chatting with The Kinks' lead guitarist about Village Green Preservation Society

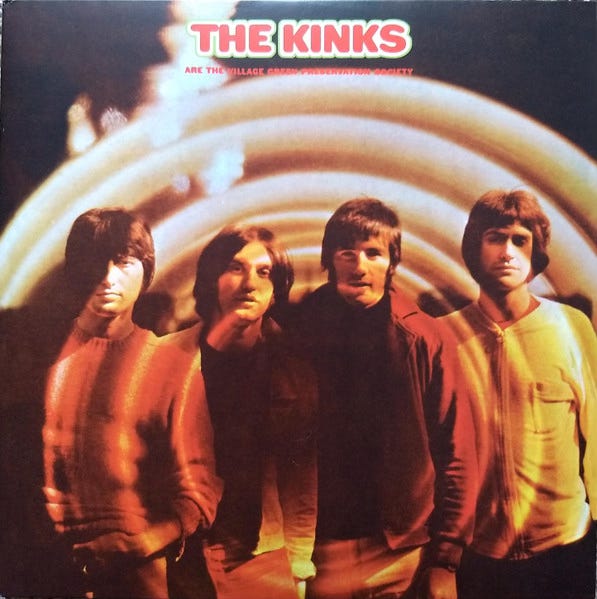

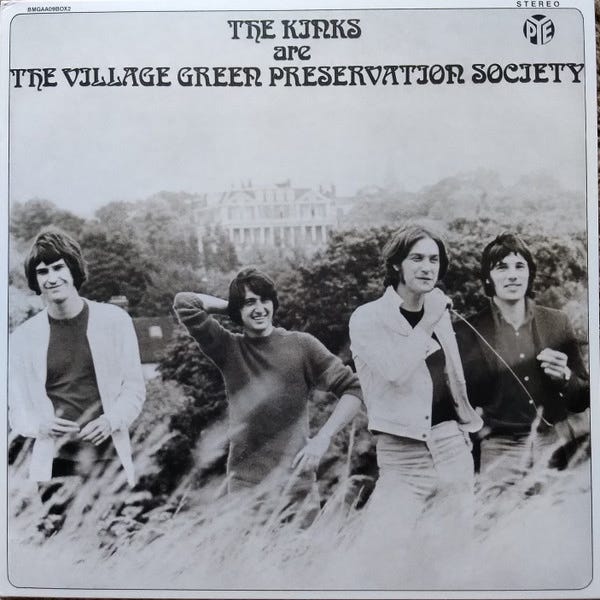

Yesterday, November 22, marked the 57th anniversary of The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society, one of my favorite albums by anyone ever.

Whether you know me in real life, through this Substack or on social media, you are probably well aware by now that The Kinks are my all-time favorite band. A quick search of the JTL archive reveals four posts (so far) and one CROSSED CHANNELS podcast episode devoted exclusively to the work of Ray Davies & Co. and what it means to me, as well as at least six others where the band just happens to pop up in the course of the conversation. Over 47 years since Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 introduced me to the band via “A Rock N’ Roll Fantasy,” The Kinks are still never far from my thoughts or my turntable.

Not that I’d staunchly defend every single song or album in the band’s extensive catalog; I’m not at all ashamed to admit that I find 1974’s Preservation Act 2 even less appetizing than the most egregiously arena-oriented installments of their oft-reviled eighties/nineties output. But the best Kinks stuff (and there’s a considerable amount of it that falls under the heading of “best”) continues to resonate with me as deeply — and in some cases even more so — as it did back in my teens.

Case in point: Their 1968 masterpiece The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society, an album which I first heard in its entirety at the age of 18 via a Portuguese import copy (the record had been long out of print in the US by then), and which I find just as wondrously enchanting over 40 years later. A Ray Davies-penned concept album comprising 15 songs about life in a small, picturesque English village, VGPS certainly hit a deep nerve with my inner Anglophile back in 1984. But listening to it these days, I continue to marvel at how perfectly its pastoral melancholia and whimsical appreciation of life’s smaller joys mirror where I’m currently at, both geographically and in my own heart and head.

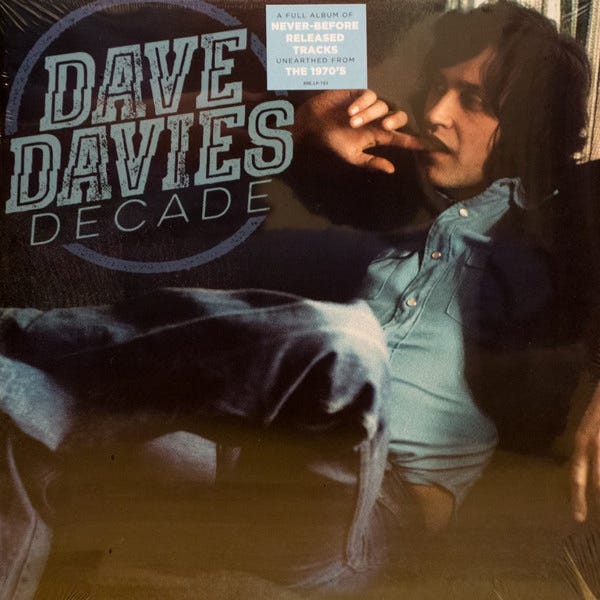

Back in 2018, I interviewed Kinks lead guitarist Dave Davies for a FLOOD magazine feature about the 50th anniversary of this magical album, and about Decade, an archival collection of Dave’s previously unreleased solo tracks that had been written and recorded between 1971 and 1979. Fleshed out and compiled with the help of his sons Simon and Martin, Decade offers a fascinating glimpse into what was happening in Dave’s creative life at a time when his older brother Ray was completely dominating the Kinks’ recorded output. Dave, quite understandably, wanted to talk about Decade as well as VGPS — though as we’ll see, there are some common threads tying the two very different projects together.

I ran our interview in full for the first time last December as a treat for my paid subscribers, but today I’m reposting it for everyone to read. I do have a number of pretty amazing interviews currently on deck for my paid subscribers — including some archival chats with Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull and Justin Hayward of The Moody Blues, and more recent ones with The Zombies’ Colin Blunstone and Darian Sahanaja of Wondermints/Brian Wilson fame. So if you dig this kinda stuff, a paid subscription to Jagged Time Lapse will get you access to those chats and all the other cool interviews I’ve already posted (like this one with Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera, or this one with Ian Hunter) plus all the completed chapters of my musical memoir in progress (like this one about discovering marijuana and Foghat Live on the same bus ride), and all the full episodes of CROSSED CHANNELS, the monthly music podcast I do with my friend and fellow scribe Tony Fletcher. And it’s all available for your reading pleasure for a mere $5 a month or $50 a year. Such a deal, right?

So noe, let’s flash back to the afternoon in October 2018 when I had the profound pleasure of speaking with Dave Davies about the small wonders of The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society. I was expecting to hear first from his publicist, who would then patch me in to Dave — but when my phone rang at the agreed-upon time, it was Dave’s cheery (and unmistakably high-pitched) voice on the other end…

Thanks for calling, Dave. I wanted to talk to you about Village Green Preservation Society…

Oh, good. And maybe we can also give a mention to Decade!

I was gonna get into that with you, as well.

Oh, great, that’d be great.

That’s actually a good place to start, now that you mention it, Village Green is being reissued at almost the same time that Decade is coming out. What’s it like for you to go back and listen to all of these old songs again?

Well, obviously, these are two very different projects. The Decade album is an album of previously unreleased recordings of mine as a solo artist, which were recorded in the seventies and have been sitting around in various forms since then. We decided to finally try and get the thing organized, and get it together; it’s finally going to be released on the 12th of October, so I’m very excited. My son Simon produced it, and my son Martin helped to collate the material and gather it all together; without them both, it would never have gotten finished.

It sounds fantastic — it actually comes across more as an album than as a collection of tracks.

Oh, cool! That’s good. That’s great.

But when you listen to those songs, or the songs of Village Green, do they take you right back to the time when you made those recordings? Or do they feel like something from an era that you feel completely disconnected from?

Well, Decade, whenever I listen to it, is full of mixed emotions; it flashes me back to a time when I was going through a lot of inner change and inner turmoil about things — my observations about my life at the time. It’s a very personal album. I mean, with Village Green, obviously the songs are mainly Ray’s songs. But we worked on them very closely together, because the concept, the idea of an album about a village green, it touched on a lot of characters [from our own lives] that weren’t too dissimilar to the people in the fictitious version of Village Green — the shopkeepers, the neighbors, the crazy old woman that lived down the road…

Who became “Wicked Annabella,” right?

Yeah. Ray’s a very visual writer. “Wicked Annabella” is based on probably a couple of different characters — the crabby old lady that didn’t like kids running on her lawn, and that kind of thing. [laughs] I think a lot of the characters were based on real people, at some point. Thinking back at the time over our lives, [our] growing up in Muswell Hill and Fortis Green, obviously there was a lot of nostalgia for the past and people we knew, so that figured greatly in forming the characters.

There is a definite sense of nostalgia on that record, but I was curious as to whether it was nostalgia for a world you actually knew, or nostalgia for an era that pre-dated your existence.

Well, it’s probably both. Me and Ray were brought up in a big family with six older sisters, and an extended family of uncles and aunts. My parents lived through two World Wars, which touched very closely on the heart of England — the working class, and how they had to cope with the situation. So obviously, there was quite a back-story behind these people, who would pop their heads around the corner, as it were, many times throughout our childhood. And eventually, it formulated into Ray’s imagination.

At the time, we were banned from America [due to sanctions from the American Federation of Musicians, which lasted until 1969]. I was very happy to be back in England, and continue my relationship with friends and local people. The Kinks were always very connected to family, and people that we knew from our past. [The album is] kind of like a loss of innocence, and a lot of, not regret, but thoughtful feelings about the past that maybe weren’t so bad. It was a time to reflect on the good things in the past, but also to try and think about the new things that were happening, and integrate both to build a happier, more harmonious future. And I think that’s the message of the album — the theme, really.

At what point did you realize that this would be an album with a specific theme?

Well, obviously, when Ray had come up with the idea of the Village Green Preservation Society [laughs], it was very thematic in just the title. And at this time, we were very close, and our families were very close; we used to see each other all the time. So I was privy to a lot of the stories and characters of that project. And there was a lot of quirky things coming out of England in the fifties and sixties, things like the Berkshire Teacup Society — these weird and wonderful English things that we thought were quite normal. [laughs]

A lot of English bands at the time were really celebrating and drawing upon their Englishness, like The Beatles with Sgt. Pepper’s. But The Kinks really seemed to be on a different trip altogether.

Yeah, it’s very different from other albums, and I think that’s what makes it so unique. When you look back, you realize how special and unique that album was at the time. It’s funny, I was thinking about this: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think the week that Village Green was released, the Beatles’ White Album was out as well — and that album sold two million copies, and Village Green sold twenty thousand. [laughs]

Yeah, that’s exactly what happened.

It was a very strange time for us. But over the years, the Village Green album gained a lot of respect; a lot of writers and all sorts of people gravitated towards this album, which was really set apart from everything else that was out at the time.

When I was growing up and getting into your music, the people who were into Village Green were almost like a secret society. Most Kinks fans, at least in the US, had no idea it even existed — but those of us who knew about it thought it was the greatest thing you ever did.

Yeah! [laughs] Well, when you listen to it, it is an invitation, in a way, to catch glimpses of this almost surreal world. It’s got some interesting kind of Alice In Wonderland-type notions that go with the songs. It’s quite trippy, man, in a lot of ways! [laughs] Although it’s also about real things — whatever “real” is, anymore. [laughs] It conjures up a vision of community life in England that’s very emotional. And also, with Decade, when I was flashing back to those memories, and the emotions I felt about real people that I grew up with… I had very close relations with friends at school that appear in songs like “Midnight Sun”. I had a best friend, George Harris, and we learned guitar together; we were going to form a blues band together. It’s important to nurture these feelings, and to consider them in the present day. I don’t know about you, but I think as you grow older… How old are you?

I’m 52.

Oh, you’re a young man! [laughs] You know, certainly as I’ve grown older, I’ve come to think that nothing gets wasted, as far as memories. When you write, the past is always informing the present and the future at the same time.

It’s certainly a well that can always be drawn upon, at least if you’re in the right frame of mind.

Yeah, it depends on how it takes you, you know. Inspiration is a strange thing! [laughs]

One of my favorite tracks on Village Green is “Wicked Annabella,” which you sing. What do you remember about recording that track?

Oh, well, not a lot, really. A lot of these recordings were very in-the-moment. Ray and I would start working with the vocal, and I would learn the vocal… I always loved the bridge in “Wicked Annabella,” always loved singing it, with the key change and everything. When I include it in my solo shows, my live shows, I do a version with two bridges, because it’s such a fun part to sing. And also, I’ve done some paintings of some of the characters from Village Green; they’re going to be a part of an exhibition that’s going to be in London in the first week of October. So I’m looking forward to that. I’ve painted my version of Wicked Annabella, and Monica as well; Phenomenal Cat, I’ve done a painting of that and what it represents. It’s an opportunity to revisit earlier music, while also trying new things like art.

Like you say, they’re such visual songs — we’ve all conjured up images in our mind of what these characters look like.

Yeah, like, I particularly enjoyed doing the painting of Monica; I called it “Monica Moonlight,” with Monica coming out with the moon high in the sky, and various surreptitious things going on. [She’s] the local hooker, basically — but also romanticizing it, thinking back to a part of your life where there were adult things going on, but it was still an innocent and emotional.

I’ve always wondered — is that you doing the sped-up voice on “Phenomenal Cat”?

What, the Mickey Mouse-type thing? No, that’s Ray; Ray’s singing that. I always thought “Phenomenal Cat” was a very psychedelic, kind of spiritual, mystical character, really. I like it particularly because it’s about strangeness; it’s about issues and feelings that we all think about. Is the universe a boat without a paddle? Or is some supreme being standing there? [laughs] We all think of these things. I also did a painting of Big Sky, which relates to it — though all the songs relate to it in some ways.

With the exception of “Wicked Annabella” and “Last of the Steam-Powered Trains,” the album doesn’t really rock in a conventional “Kinks” kind of way. Was that frustrating for you at the time?

No, I fell very happily into it! At the time, me and Ray were close; we used to go to the pub with our families, and play bar billiards, talk about football and the people we knew. It was all very much a part of the process of making Village Green — “Do you remember so-and-so?,” that sort of thing. I did a painting of Walter as well, by the way. So yeah, I fell right into it. You have to remember that, throughout the whole Kinks’ career, the subject matter has been very varied. It’s not just all hard rock; there’s light and dark and small and loud — every color you can think of. It’s like painting, you know?

That’s one of the things I’ve always loved about you guys — there are so many different periods to The Kinks, so many different albums, so many different flavors.

If you consider it like a movie, for instance, it’s like a whole story. You can’t do heavy, dark music constantly throughout it. You use it in a way to explain an emotion; it’s all covered with light and dark and all different kinds of things. I think that’s what the great joy of being in a band like The Kinks, is that it’s been such fun. And maybe we might still yet do something…

I wanted to ask you about that. Any further news on the possibility of a Kinks reunion?

Well, I’m in New York at the moment; but when I’ll be back in London for the gallery event, me and Ray will be getting together to talk about this, that and the other. So, we’ll see! [laughs]

Village Green was the last album you did with original bassist Pete Quaife. Was he just losing interest in the band at that point?

I don’t think there would have been The Kinks without Pete Quaife. I think he was really crucial in the early days. He really helped me and Ray; he was very funny, he was very imaginative, himself. And he grew up with all these characters, like Ray and I. But that year [1968], “Days” was out as a single, and I remember Pete in the studio, there was an analog tape box, and Pete was writing something on it. And where it had the name “Days,” he wrote “Daze”. So I thought, “Okay, Pete…” [laughs]

The thing is, me and Pete had a special relationship. If he said, “I want to fly to the moon,” I’d have said, “Okay, let’s do it.” But he wanted a change, something different in his life. Ray was reaching the heights of his writing process, really, and I think it was a very frustrating time for Pete. But it would never have been the same without him.

Do you wish he’d hung around for a few more records?

Well, yeah, but you can’t force people to be what they’re not, you know? It’s like a marriage where you hang on and hang on and hang on, and you end up hating each other. Sometimes! [laughs] Sometimes. But it can happen! [laughs]

So it was probably for the best, then?

Yeah. But a part of the Kinks died after Village Green, I think, with Pete leaving. But you leave one thing, and start up another; it’s what we do as human beings. Well, maybe “died” isn’t the right word, but we definitely changed after that.

The songs on Decade — were any of them things that you brought to the Kinks and were rejected?

No. Strangely enough, I always thought they were incomplete, still in a state of being written. And the songs were very personal; I thought they maybe wouldn’t fit on a Kinks record, and I wasn’t going to have a big, drawn-out debate with Ray, because he was going through a very prolific time in a completely different direction. I needed to get these inner feelings out; I needed to express myself. So I’m glad that, after all this time, Decade finally sees the light of day. Because it would have been a shame if these songs had never been released. So I’m very happy about it coming out.

I don’t think most Kinks fans even realized that these songs existed.

Well, with The Kinks, there was always something going on behind the scenes, a back-story or a secret life. [laughs] When Simon first started playing me the mixes of Decade, it was a very emotional time for me. And thank god, Simon, he’s a great musician, but he’s also very into the technical side of audio. He got it, and he got the emotion, and the things I was talking about.

The more I listen to Decade, the more I gravitate to a song called “Web of Time,” which says a lot from my point of view about where I was in terms of looking out upon the world and what’s going on. It relates to all of us, “Web of Time”. Because everything changes, but some feelings don’t change. It’s interesting. And some of the songs highlight aspects of my spiritual life that I was learning about and grappling with, and wondering how to integrate them into my everyday life.

That’s a big sub-thread behind the songs; I kind of had an emotional breakdown in the early seventies, and this emotional breakdown was a part of me discovering the spiritual side of all our natures. I believe that we’re all much deeper than we think we are, and we’ve just begun the journey of learning who we are as human beings. And that’s a conversation for another day, but there’s a lot of learning and self-awareness in these songs.

Well, Dave — I know our time is up, but I just wanted to say that this has been an absolute pleasure. I’m so glad that you’re still with us, and still making music and art. Thank you for speaking with me.

Well thank you, Dan. It was a pleasure to speak with you. You take care now. Bye bye, cheers!

You may also dig:

1. Though I liked much of Preservation Act 1, I'm like you, I found Act 2 almost unlistenable.

2; The Village Green period gave us many of the songs that ended up on The Great Lost Kinks Album, which is my favorite by those guys.

3. I liked Dave's contributions to TGLKA but I never listened to Decade; I was pretty much done with the Kinks after 1976 but now I kinda want to give it a spin.

I don't know how long is the list of things that we have in common, but the Kinks being the favorite band is at the top. I'm very happy that you made this available to your non-paying subscribers.

I shared this on my Facebook page, although I don't think that it will get much reaction. I'm hoping to be pleasantly surprised.