JTL Flashback: Coffey is the Color

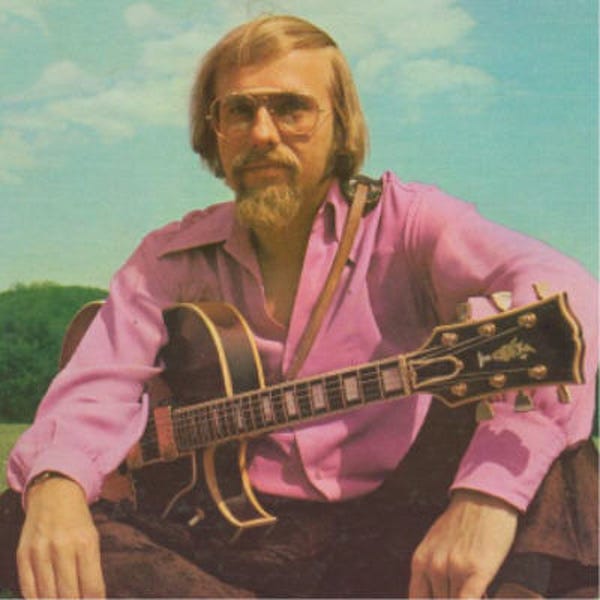

An interview with legendary Motown funkmaster Dennis Coffey

Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers — and welcome aboard to everyone who has subscribed to this newsletter in the last couple of weeks, especially those of you who enthusiastically picked up on what I was layin’ down in my piece on The Clash’s London Calling.

Today, I’m re-running an interview with Detroit guitar legend Dennis Coffey that was originally posted in November 2022, just a few months after I first launched Jagged Time Lapse. At the time, it was available only to my paid subscribers, but I’m making it available to everyone today — both because I think you’ll dig it, and because it’ll give you a free taste of some of the goodness my paid subscribers receive.

During my three decades as a music journalist, I’ve interviewed a lot of interesting folks for a wide variety of publications including Rolling Stone, Revolver, Guitar World, FLOOD and The Forward; however, due to space restrictions and other issues, these interviews have rarely run in their entirety (and sometimes not at all). So I’ve been exhuming some favorite interviews for my paid subscribers — like ones with Dave Davies of The Kinks, Noddy Holder of Slade, “Space Age Bachelor Pad Music” visionary Juan Garcia Esquivel, and the late, great Ozzy Osbourne — as well as running the complete Q&As from more recent interviews I’ve done, like this one with Paul Weller. I also have some wonderful new chats in the can with Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera and Colin Blunstone of The Zombies, which will be running here in the near future.

For just five bucks a month (or $4.17 if you opt for an annual subscription), you can enjoy access to all of this exclusive material, along with the completed chapters of my adolescent musical memoir-in-progress — like this one about discovering marijuana and Foghat Live on the same bus ride, or my ill-fated first “band practice” — and all the full episodes of CROSSED CHANNELS, the monthly music podcast I do with my friend and fellow scribe

. (We just released our 20th episode, which focuses on Bruce Springsteen circa 1973-75.)I think that’s a pretty solid value for just the price of one large coffee drink or pint of beer per month — and if you do too, and would like to support good independent music writing in this dire media landscape, please click the button below and head to the “paid subscription” option. A thousand thanks to all of you who have already done so — you quite literally keep the lights on over here. (And FYI: if you already have a paid JTL subscription but find that you can now no longer access my “paid-only content,” the credit card you have on file may need to be updated.)

And now, on to today’s program…

I was a fan of Dennis Coffey’s guitar playing long before I ever knew his name. The wicked wah-wah on The Temptations’ “Cloud 9”? That freaky fuzz on Wilson Pickett’s “Don’t Knock My Love”? The spritely intro of The Spinners’ “It’s a Shame”? Those trippy Echoplex licks that drip all over The Dramatics’ “In The Rain”? That’s all him, as of course is “Scorpio,” his wicked 1971 funk instrumental, which soundtracked many of my car rides to kindergarten.

As a member of Motown’s Funk Brothers studio band who also played numerous sessions for such Detroit labels as Revilot, Ric-Tic, Golden World, Hot Wax and Invictus, Coffey’s sizzling six-string stamp is all over a ton of the greatest soul and funk records of the late 60s and early 70s.

Coffee also released several searing slabs as an instrumental solo artist, wrote and recorded the soundtrack of the immortal blaxploitation flick Black Belt Jones, produced recordings by artists including Rare Earth, Rodriguez and Gallery, masterminded the disco studio group CJ & Co (best known for their 1977 hit “Devil’s Gun”), and — until the pandemic ended his 11-year run — was a weekly fixture at Detroit’s Northern Lights Lounge. I sadly never made it to one of those gigs, but the performance of his that I did catch at SXSW 2011 was absolutely incendiary.

Back when I was helping put the Stompbox books together, I made a big push to include Coffey in the mix, and he and I wound up having a very enjoyable chat in November 2019 about his use of guitar effects through the years. Unfortunately, the conceptual restrictions of the book — we specifically wanted to feature one of his Motown-era pedals, but the Motown Museum never responded to our requests to photograph them — meant that this interview ultimately ended up on the cutting room floor…

When did you first start using effects pedals, and what were they?

The first one was the Tonebender — what was that? A Vox or something? Yeah, for fuzz tone, that was the first one I used. We were recording a young group called Mutzie, and the guy had one of those, and I said, “That really sounds cool!” You know, if you let the battery wear down for a day, it had a kind of a sweet sound to it. So I was using that. And then at the same time I started using the Cry Baby wah-wah pedal.

How did you get hip to the Cry Baby?

A good friend of mine, Joe Podorsek — he was a guitarist, and he was also a classmate of mine, and he owned Capital Music, him and his dad. So basically, anytime anything new came in, he’d say, “Just take it and try it. If you like it, keep it; and if not, bring it back.” So I had access to everything new through him, and I used that wah-wah on The Temptations’ “Cloud 9,” which was the first session I ever did for Motown. That was the first time a wah-wah had ever been used on an R&B record.

Were the other musicians on the session, like, “What the hell is this?”

Yeah, some of them. [laughs] Some of the Funk Brothers who didn’t know me were looking at it and wondering what it was. But I’d been hired by Motown to be in this producers’ workshop; and this producer, Norman Whitfield, he had a vision of getting Motown into the psychedelic era. So we were running down the chart for this song, “Cloud 9,” and I put my wah-wah on the front of that and Norman says, “That’s what I want!”

Within two weeks I was recording it with The Temptations, and then I was there all the time, using my fuzz and my wah-wah and my Echoplex, and anything else. Norman would say to me, “What do you got today?” He was pretty good about letting me create intros and all kinds of stuff; the introduction to “Ball of Confusion,” I created that right on the spot.

We did all that stuff when we were tracking; I did no overdubs whatsoever at Motown. We’d do one song an hour with no mistakes and made ‘em hits. We sat in front of an arrangement we’d never seen before, and we had to read the chart correctly because they had great arrangers at Motown. We’d do one song an hour with no mistakes, and made ‘em hits.

Did you have to spend any time during the sessions messing around with the pedals to find a sound you liked?

No, they wouldn’t let you — you didn’t have time! [laughs] You can’t do one song an hour when you’re horsing around trying to figure out how to use a device or a stompbox.

Do you still have any pedals from the Motown days in your possession?

I donated two of them to the Motown Museum, along with a Gibson 335 guitar that I was no longer using. If you go to the Motown Museum, you can see it all set up there where I used to sit, with a music stand and a wah-wah pedal and a cord; I hooked it all up like I used to back in the day.

So it’s in the studio area of the museum?

Yeah — if you go into Studio A at the Motown Museum, you can see it, along with a thing with my name and face on it showing that it’s from me. And then there’s also a big poster of me in the museum gift shop. [laughs]

Were those pedals — the Vox Tonebender and the Cry Baby wah — the same ones you used on your solo hits like “Scorpio” and “Taurus”?

Oh, yeah.

So you were pretty good at finding way to get new sounds out of them and work them into new grooves.

Oh yeah — because I was working four nights a week with Lyman Woodard and Melvin Davis at a Black club where we were doing funk and jazz, so it was a great opportunity for me to play in front of people that weren’t dancing, and were actually listening to the music. [laughs] So that was a great experience for me.

What was the name of that club?

We were working at this place called Morrie Baker’s, which was a mile and a half down the road from Baker’s Keyboard Lounge. And what we used to do, when I was with Lyman and Melvin, we would have our psychedelic thing. I bought a strobe light and stuck it onstage. [laughs] It was like a piano bar stage. So when we would get into that thing, Melvin would switch off the stage lights because the switch was right by him, and I’d kick into my fuzz tone stuff and switch on the strobe light. Man, the people were going crazy! [laughs] I could feel the people rising up in the seats in front of me when I’d bend a note with that fuzz on it!

Some of the guitarists we’ve talked to for this book have certain pedals that they use in the studio and certain ones that they use onstage — but it sounds like you were using the same tools of the trade in both places.

Yeah, you have to — because that’s the way you learn to use your pedals. You can’t just screw around with them at home. I’m a firm believer in playing out as much as possible. I still play every Tuesday night at the Northern Lights Lounge, which is two miles away from the Motown Museum; and I’ve been there for eleven years packing ‘em in. You have to be in front of the people; you have to play stuff for them. And that’s how you figure out what works and what doesn’t work. If you’re trying to get the people and communicate with them and it doesn’t work, you quit doing it.

Was there ever a moment where Norman Whitfield told you that what you were doing on a song was way too out there, and that you needed to reel it in a little?

No, he never did that. Norman knew I was the guy who was gonna help him bring Motown into the psychedelic stuff, so he was always saying, “What do you have today?” Like, the intro to “Just My Imagination” — I made that up on the fly. Norman gave me a lot of opportunities to do that, and every artist that he had he used me on. And so the other producers started using me because of that.

Norman was the master of dynamics; he was always breaking things down and bringing things up. Norman Whitfield was never in the control room; he was always standing in front of the two drummers, Pistol [Richard Allen] and Uriel [Jones], and he’d be breaking stuff down. We’d be in there in August, and it must have been 100 degrees, [laughs] and he’d be counting it off right in front of the drummers and then away we’d go.

Your list of session credits is pretty amazing. A lot of people don’t know that you were on Wilson Pickett and Dramatics records as well as the Motown stuff…

I used to go down to Muscle Shoals to record with Wilson Pickett. I had a thing called a Condor Unit which was made by Hammond Organs. It was like a tabletop unit that had organ stops on it, and you could get a bassoon sound, an oboe and all kinds of stuff out of it. I had a guitar specially modified with a pickup from Hammond to use with that, and I used it with Wilson Pickett at Muscle Shoals on “Don’t Knock My Love,” “What You See Is What You Get” by The Dramatics, and “Smiling Faces” by The Undisputed Truth. It was pretty neat.

I’m guessing you had to have been a fan of psychedelic rock. Who were some of the guitarists of that era that you were paying attention to?

Well, I liked some of it. I listened to Hendrix and Clapton and the way they used the wah-wah, and I listened to some other psychedelic stuff, especially for the fuzz tone use. But I was also listening to Wes Montgomery, and I was certainly listening to all the R&B stuff. You know, I started off with that stuff — I was playing on those Northern Soul records in ‘63 and ‘64, like The Volumes and Darrell Banks and those guys. And I was playing with The Royaltones when we backed up Del Shannon; I played on “Handy Man” with Del at Bell Sound in New York. And from there I went to Golden World, and I was playing with J.J. Barnes and Edwin Starr and all that stuff. It was just a progression; I was playing in the Black clubs, and I was playing all the funky stuff and playing all the sessions.

Me and Bob Babbitt, we played guitar on all those soul sessions because we could both read music. That was important. I got a call from Golden World one time; they wanted to hire me for a session. I said, “Well, when’s the session?” They said, “Right now!” So I took my three year-old daughter with me and put her in the corner and read the guitar charts. And then I was at Golden World every day.

I see from your website that you use Boss pedals now. How did you get into Boss stuff?

I just started trying different things that worked, and Boss was pretty aggressive at coming up with new pedals. The worst thing you can do is get pedals made by different manufacturers, because they won't work right together. So Boss came up with this case where I have three pedals in it; I can mix and change the pedals, but they're all in just one small case that I can carry to the gig. And then I have a Boss tuner that I hook up in front of the Boss pedal stuff.; it’s all very simple to hook up, I can change those pedals whenever I need to, and it just all works together as part of a system. And if one pedal stops working, I just throw it in the garbage; screw it — it’s not that expensive! [laughs]

The worst thing is if you have some huge pedal board where you’ve got like 10 pedals or something on it. That’s unnecessary. I have enough trouble playing the six strings; I don’t have to worry about 10 pedals on top of that. I’d drive myself crazy! [laughs]

So which Boss pedals do you usually have in your carrying case?

Let me just open up the case real quick… What I’m using right now is the Blues Driver, which I use for distortion; and then there’s the Phase Shifter, and then there’s the Delay. And sometimes I might take the Phase shifter out and try the Super Chorus in the middle.

Do you use the Phase Shifter and Super Chorus for more psychedelic textures?

It’s not really psychedelic; they just kind of fit into anything. I think the Blues Driver combined with those pedals makes it a little more psychedelic. But whatever you’re using, it’s gotta fit in with the playing of the group. I don’t use those pedals on every song; I just use ‘em on the songs that need ‘em. On things that I used the Echoplex on, like “In The Rain” by The Dramatics, I use the Delay instead of that.

I don’t use the wah-wah on the gig much anymore because I’m just past that. [Motown guitarist] Melvin Ragin, he got the nickname “Wah Wah Watson” — he made a career out of using the wah-wah pedal, but I was already past that by then. He actually sent me a new wah-wah pedal in the mail many years ago. Wah-Wah has since passed away, but he was a good guy.

I wanted to ask: Were you paying much attention to what was happening on the rockier edge of the spectrum in Detroit at the time — like The MC5, Bob Seger, or even Funkadelic?

Oh, I played on the first Funkadelic album — I did overdubs on that. And George Clinton’s first record, “(I Wanna) Testify” with The Parliaments, that’s me and Eddie Willis playing on that. And I recently ran into the guy from The MC5 that was doing something, so I played live with him.

Wayne Kramer?

Yeah, Wayne Kramer. In fact, I remember opening up for The MC5 at the Grande Ballroom. Me, Lyman Woodard and Melvin Davis. There was so much weed in the air, man, you got a contact high just being in there! [laughs]

Oh man, I bet!

And when The MC5 got up, they were so loud I had to go stand in the parking lot! [laughs]

That’s a double-bill I would have loved to see. Did the 5’s crowd dig what you guys were doing?

Oh yeah. I started off with the Wes Montgomery version of “A Day in the Life” by The Beatles, and right away the whole room lit up, man. They got it!

I know a lot of the Motown old guard are gone, but do you still keep in touch with any of the cats who are left?

Not too much — just who’s ever up here. And you know, the Funk Brothers, there’s only three of us left. There’s me and Joe Messina, and Joe’s in his nineties, so he doesn’t play out that I know of. [NOTE: Joe passed away in April 2022 at the age of 93.] And there’s Jack Ashford, who was the tambourine guy, mainly. He’s down in Memphis. There’s no one left. Eddie Willis and all those guys are gone…

It must have been incredible to be a part of that.

Oh yeah. I mean, to be a member of the Funk Brothers? That was the finest studio band in the world, man. There was one year where I was on three songs in the Top 10 and ten songs in the Top 100 for a year straight.

And then your own records were doing pretty well, too.

“Scorpio” was a gold record, “Taurus” was in the Top 20… I was just rockin’ it, man.

CJ & Company — that was you too, right?

Yeah, me and Mike Theodore were producing a lot of stuff at that time, and CJ & Company was one of them. We were partners for years, and CJ & Company were one that we found and first put together under another name. I can’t think of what the other name was. [Note: It was The Strides]

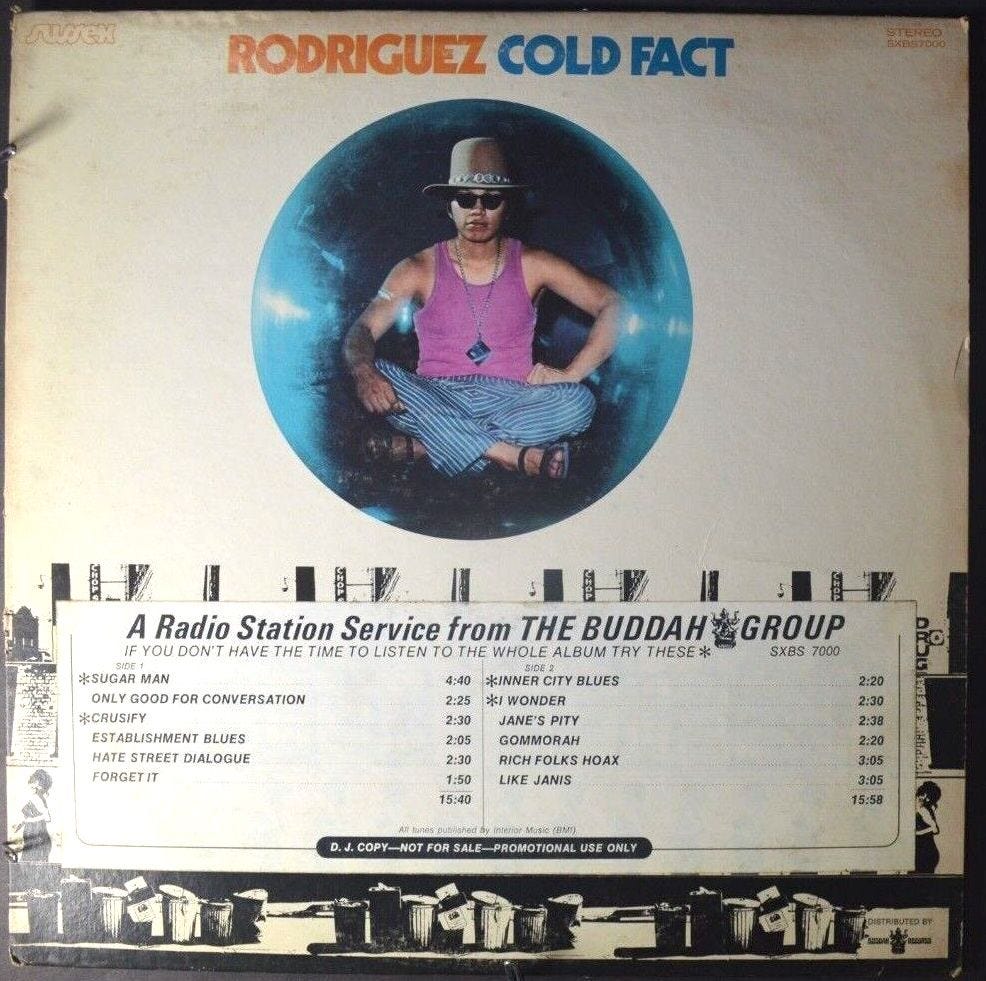

I also wanted to ask you about Rodriguez, who has become quite the cult hero in the decades since you worked together.

Well, Rodriguez, he was always kinda, you know… Rodriguez. We used to meet him wandering around by Wayne State, which is where I got my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. So he’d be wandering around down there and he had one of those little Italian bags of wine, and he’d be kind of like a ghost. We’d never meet him at his house, me and Mike Theodore; we’d meet him out on the street corner somewhere. He was so shy when we went to see him play, he was facing the wall. And I said, “What the hell's up with this?” [laughs]

So anyways, what we had to do with Rodriguez is, we brought him in the studio and recorded the first four songs of the Cold Fact album by himself. And then we built a band around him; I played bass guitar and stuff on that. And then he got more comfortable, so we could record him in the studio with the band. His songs were so good, but he only really had that Cold Fact album as the one, you know. He had another one, Coming From Reality. We only had about three cuts off of that, because he wanted to be Elton John and he went to London to record the rest of it. He should have recorded the second album with us here, but…

How did your solo career come about?

Mike Theodore and I, we were writing orchestration for horns and strings, rhythm, everything. I mean, we’d bring in 20-man string section, viola and cello, we'd write for all that stuff. So I thought to myself, “Well, what would it be like if I did a guitar band approach instead, where I was writing orchestrations for guitars like I’d write for a full band. So I wrote 10 songs on my Sony sound recorder, and I overdubbed them to show Mike what I was talking about, what I wanted to do. And he got Clarence Avant at Sussex Records to give us a deal. I gave a copy of “It’s Your Thing” [an instrumental cover of the Isley Brothers classic, recorded by Coffey in 1969 for LA’s Maverick label] to Motown; I gave it to Hank Cosby over there. Hank Cosby told Clarence, “Barry wants to sign him. He loves that stuff!” I said, “Well, it's too late. I'm already signed!” [laughs]

So I went in and did that Evolution album, and that’s where I did the guitar band stuff on “Scorpio” — there’s like nine guitars playing the melody. I had Ray Monette from Rare Earth and my buddy Joe Podorsek on guitar, and I wrote out charts for each of us after we did the rhythm sections. I wrote the guitar charts like horn charts; that way you could put fuzz tone on each guitar, and you could blend it all together so it sounded like horns. And then I ran a bass through a wah-wah pedal to get a low trombone or a baritone sax sound at the bottom of that. The Cry Baby would give it that trombone wah-wah sound, or like trumpet with a mute. The wah-wah gave more expression to the guitar, I think; and because of the way the pedal works, you can really control exactly how much of the effect you’re using on any note.

It’s interesting that you used fuzz this way, because most people don’t know that the fuzz pedal was originally invented with the idea of making a guitar sound more like a horn. But you clearly understood its potential in that regard.

Well, yeah, because Mike Theodore and I were arrangers, we were producers, and then I was a guitarist and a jazz guy and everything else — whatever was needed, you know? I think I probably have a short attention span, anyways; I'm always trying to do new stuff, and I never play a song the same way twice. I had this organ player, and when I'd go into this crazy stuff on a breakdown, he’d go, “You’re going into that voodoo shit again! What the hell you doing?” [laughs] And it works; the people show up. I mean, that keeps me honest. You gotta play for people. You can't get honest playing in your basement, just make up stuff you don't know if it works. Playing in front of a crowd, they help mold what your music's gonna be. It’s like a focus group in real time.

Another fantastic article, Dan! Patti Quatro I devoted almost an entire episode to Dennis Coffey and John Rhys-Eddins, because both of them heard about a very nascent female rock band called the Pleasure Seekers. The band had only formed a few weeks prior. This was late 1964. Dennis wrote a song for the band, and it was recorded. Unfortunately, no copies remain, but Patti was cool enough to sing it for the listeners a cappella. It was called, “Long White Line.” Just thought I would add to Dennis Coffey‘s Legacy, because he was extraordinary! Great interview! Thanks again.

Love it! Finally, I get the rest of Coffey! This came out when I was still evaluating the worth of a JTL subscription, at the time I used the money to buy some amazing Dennis Coffey albums. I reckon Dennis helped me come around to ponying up for a subscription! I'm devastatingly bummed I wasn't hip enough at the time to plant myself at the Northern Lights every chance I could. He deserves forever residuals for unintentionally laying down and creating the base soundtrack sound of 1970's porn, TV & film!