"I Hate Everything About Baseball Except Baseball"

Steve Albini on the National Pastime, Part Two

Welcome to Part Two of my previously unpublished “chinwag” (as my pal, ace songsmith/rocker and loyal Jagged Time Lapse subscriber Tim Rogers put it the other day) with the late Steve Albini from back in 2017.

The interview was filmed for The Baseball Furies, a still-in-progress documentary which focuses on baseball from the perspective of the punk, alternative and metal musicians who love it, along with several music-loving baseball players, broadcasters and journalists thrown in for good measure. If you haven’t already read Part One of our interview, you can do so here:

All the preamble and setup for our interview is already part of that post, so I won’t waste space by regurgitating it here. Let me just add, however, that contrary to the public image that he so often cultivated as a curmudgeonly, button-pushing asshole, Mr. Albini could not have been more welcoming to our film crew, or more delightful to converse with. (And as a resident of Wrigleyville-adjacent neighborhoods from 1982-1993, I heartily concur with his assessment of how night games at Wrigley Field impacted the local punk scene.) Thanks again for your time, Steve, and safe travels; you will definitely be missed…

So, how do you feel about the Cubs?

I was never a Cubs fan. I’m not a Cubs enthusiast. They put together an amazing organization and team; five or six years ago, I started envying the enthusiasm of my long-suffering Cubs fans, because I knew that things were going to turn around for them, and that they were going to be, if not a dynastic team, at least a very good team for quite some time. And I envied their budding enthusiasm.

Before the Theo Epstein era, what was your opinion of the team and its culture?

Oh, I hated it. It’s like I said earlier: I hate everything about baseball except baseball. So the Cubs as an institution, as a tourist attraction, as a novelty, as an excuse for binge drinking, as a locus of all of the bro/white cap/cargo shorts, cocksucking asshole day-trading motherfuckers — like, as the focus of that? I hate everything about it.

Wrigley Field is an incredible place to see a ballgame, though. The proximity to the field, the lack of interior advertising and that sort of stuff prior to the retrofit — which, you know, is totally appropriate when you’re building a champion-caliber team. You want to have larger capacity, and you want it to be bigger deal; I understand that. But seeing a ballgame in the eighties or the nineties at Wrigley Field was incredible.

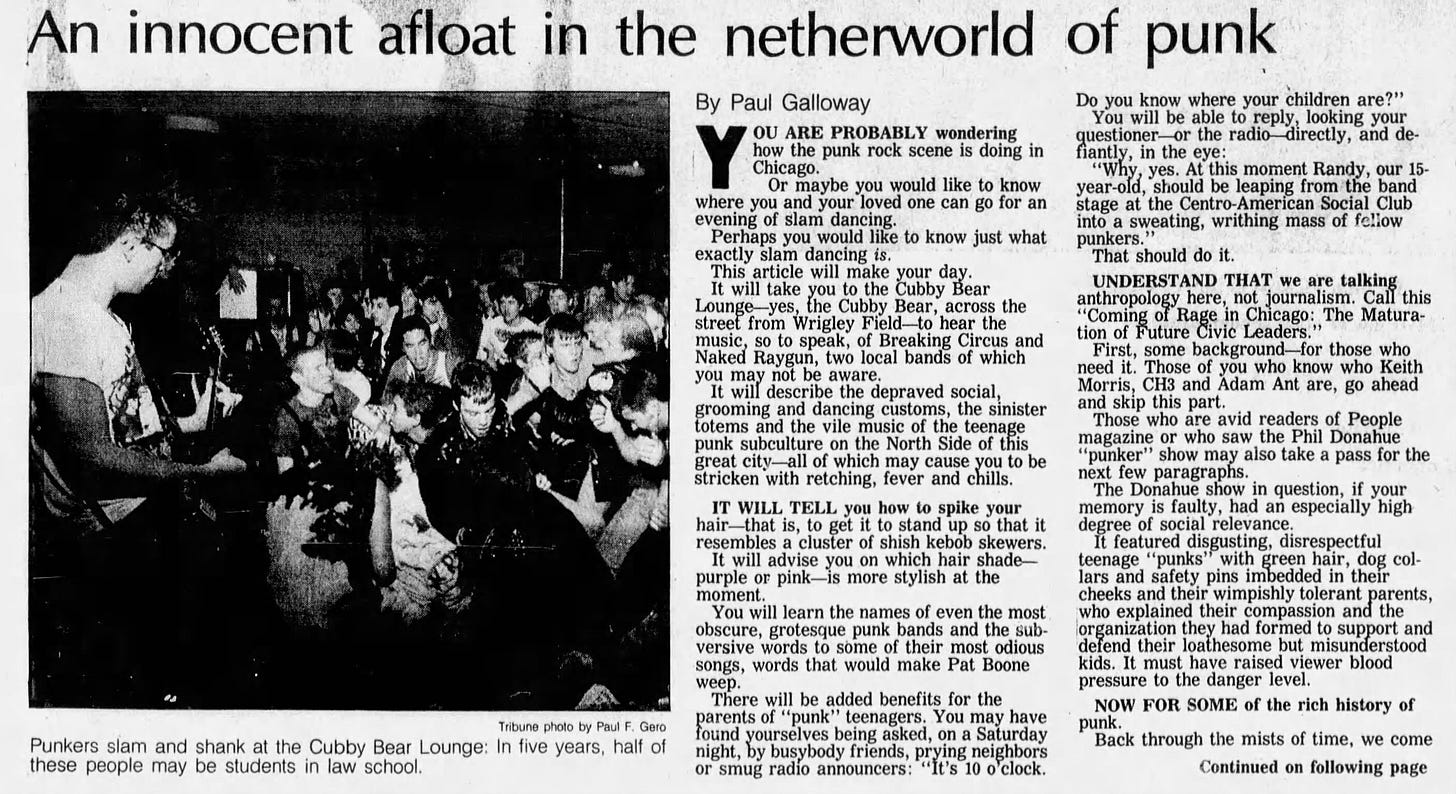

The worst thing that happened in my life with respect to the Cubs is that they added night baseball. There was a bar diagonally across the street from Wrigley Field called The Cubby Bear that was originally about the size of this room, and it was one of the few venues in town where punk bands could were welcome to play. And six months out of the year, there was nothing going on in that neighborhood; even during the summer at night, there was nothing going on in that neighborhood. So punk bands had a place that they could put on shows, that had an L station a few blocks away, that was on a major intersection, easy to get to, yada yada.

So, The Cubby Bear as an institution in the eighties was very important in the development of the punk scene, and a lot of really pivotal shows happened there. Like, I saw a lot of my favorite shows ever, in a dingy, tiny little bar that only operated for the benefit of people without jobs who could go to the ballpark in the middle of the day, and all of us grubby outcast punk rockers who occupied it at night. When night baseball came in, the entire neighborhood changed. It became a party strip, it became a hangout; it became the reason people drove here from Iowa. And that changed the music scene pretty significantly.

Though I remember seeing some great shows The Cubby Bear as late as, like, 1993.

Oh, it maintained some association with music scene through the nineties. But as it got larger and larger, and catered more and more to the white cap/cargo shorts/open-toed sandals crowd, then it it shifted away from the underground music scene and became more kind of a bar band scene. And now they occasionally have music there, but it’s essentially a sports bar. And it’s, you know, pretty giant.

Oh yeah, it’s unrecognizable now.

You know, I don’t fault anybody for trying to make a living; and you butter your bread on the toasted side, I suppose. So I can’t really fault them for indulging that, but…

So, the theme of this documentary is that there seems to be a deep connection between musicians — especially punk rock musicians — and baseball in a way that you don’t find with musicians and other sports, at least in the US. We have various theories about that, but we’re also curious as to what your thoughts are on the subject.

Yeah, I don’t know why that is. I agree that there is, that there seems to be more of an association with punk rockers — and people who are in alternative culture of all kinds — and baseball. There’s more of an affinity there than there is with other team sports, and I have no postulate why. In the strike year… was it ’94?

Yeah, 1994.

Some other bands got together with my band, and we put together a big show here in the dead of summer during during the strike. We named it after Ted Williams’s last .400 season — Pine Tar .406. And the concept of that show was immediately embraced by all the other bands that we approached, because everybody liked baseball, and everybody liked the idea of a baseball-themed show when there was little baseball going on.

My own theory is that the part of the brain that appreciates the minutiae of baseball and baseball history is also the part of the brain that appreciates the minutiae of music and music history.

Yeah, I’m bad at postulating other people's reasons for doing things. I feel like I can take a guess; but I'm normally suspicious of my guesses, and I'm suspicious of it when other people postulate a reason for why somebody else is doing something. So it’s very difficult for me to to pin it down beyond some minor inklings. I think the detail in baseball, the the fact that you can delve deeper and deeper and deeper into it does mirror the music scene. Like, if you get into it, you can get into it on a superficial level and just enjoy it; or you can find out what bands these guys used to be in and go look for their rare singles and, you know, that sort of thing. Like, I’m sure that there is some corollary there, but I think it’s overstating it for me to like pin that down any finer than that.

One thing that I think is kind of cool, though, is I can feel a kinship for people who have an affection for baseball. And that will warm me to them as people enough for me to begin to reconsider a critical opinion of their music.

More so than if music and baseball were flipped? Like, you’d be less inclined to give someone the benefit of the doubt just because they like the same music you do?

Exactly. Yeah, it seems like you can have something in common while still recognizing that you’re completely different people. But when you find somebody who’s tuned into baseball in sort of the same way that you are, you start to think, “Maybe that’s the same kind of person as me.”

The most striking example, for me anyway, is the Canadian band Rush — a band I dismissed out of hand. Their first album is actually pretty good, I found in retrospect; it’s pretty good Grand Funk-style, hard-rocking garage band kind of stuff. I actually quite like that first album. But as it got more intellectually obsessed with complexity, they lost me. And the philosophical angle of Ayn Randian lyrical content — I am absolutely not going to get on that bus. Literally, there is no way you can shake me off as a potential fan faster than [with] that kind of meritocratic bullshit talk, right? Okay.

Then I find out that Geddy Lee has been an avid rotisserie baseball player since childhood, and that every night in the summer, even on tour, he tends his team; he minds his teams every single night. Okay. All of a sudden, I like Geddy Lee; all of a sudden, I think Geddy Lee is fine, right? Then I see a picture of their stage setup where Alex Lifeson has this wall of amplifiers, just a fucking shit-million of the most expensive, high-caliber amplifiers on earth, and, you know, the rack of guitars, right? Neil Peart has like a fucking showroom of drums; he has like a warehouse of drums arrayed around him, with all sizes, all options available at all times, right? Just absurd. [But on] Geddy Lee’s side of the stage, his bass is going to an offstage amplifier that you can't even see; and behind him is a wall of rotisserie chicken ovens, cooking rotisserie chickens for the group for the crew meal after the show! I suddenly think Geddy Lee is the Best Fucking Guy. It’s hard for me to say this, but I now approve of Rush. I now think that Rush are fine, you know?

And then, the fact that he also turns out to be a huge Negro Leagues collector…

Baseball ephemera is unique to everybody. So whatever your association with baseball is, you would find things about it to like. Like, I have a Mark Fidrych autographed card — I want to say it’s a cereal box card. I can’t remember what it was. It was not a conventional baseball card; it was like a postcard or something like that, commemorating his incredible season, autographed by Mark Fidrych.

That’s awesome.

I have a Mark Fidrych autographed baseball, as well. What else have I got? I have the commemorative card for Hank Greenberg’s Hall of Fame induction, autographed by Hank Greenberg.

Is Mark Fidrych an all-time favorite of yours?

He’s a loon, you know? I really, really appreciate loons — and for some reason, pitchers tend to be loons. Like Bill Lee, another fantastic loon; I really liked him.

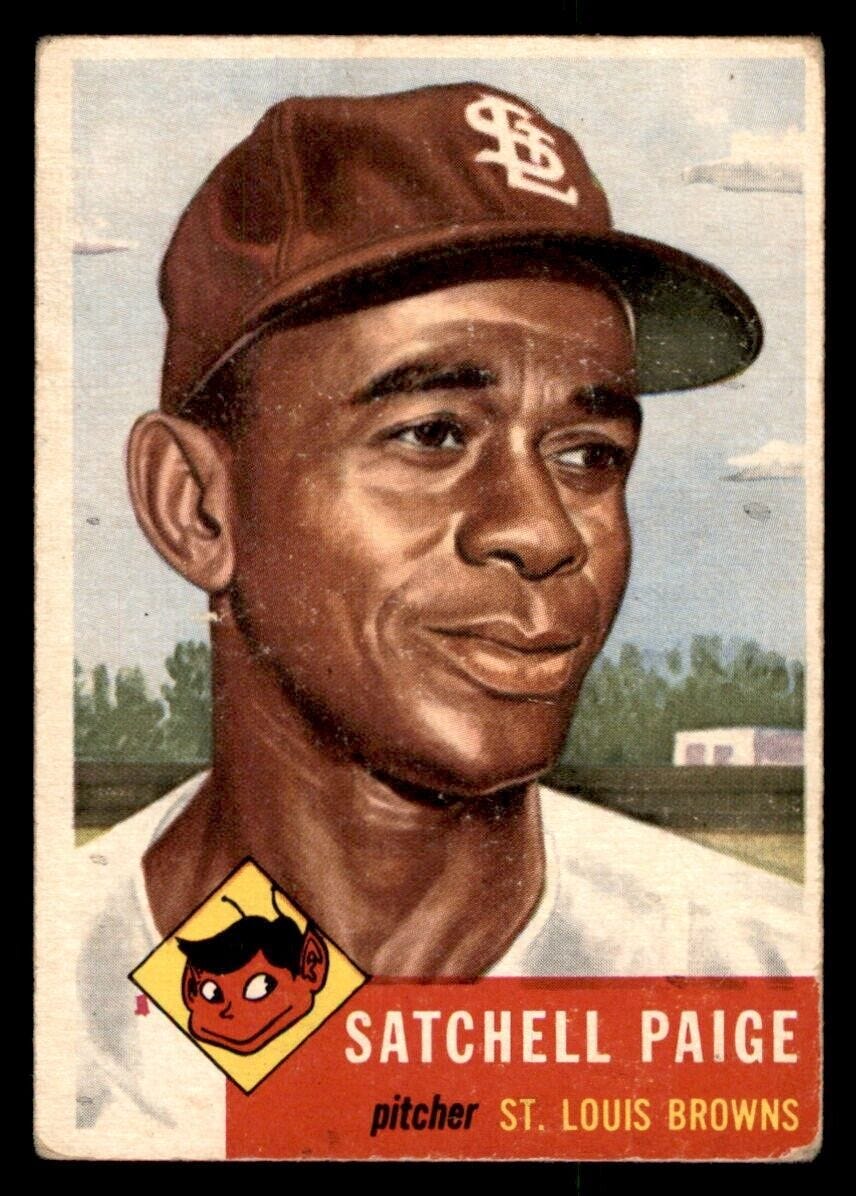

Or someone you’ve namechecked in one of your songs: Satchel Paige.

Yeah, well, Satchel Paige’s Rules for Living is one of the most concise and most beautiful life philosophies I’ve ever read. It’s really great — especially the admonition to let your limbs jangle loosely. [laughs] How great is that?

I’m in a band called Shellac of North America. And we have a song called “My Black Ass,” and that whole song is a kind of a scattershot examination of the way racism survives, even when there are black heroes, and the way their heroism is perverted into a kind of an exploitation that extends the reach and the solidity of racism. Satchel Paige is used as an example there, in that when the color line was finally broken, it was too late for arguably the greatest pitcher that ever lived to make his mark, as he should have; all of the people that played against him and all of his contemporaries, all of them said that he was an astonishing pitcher. So his reputation survived, but he wasn’t able to enjoy his skills, right? So then the color line is broken, but it’s broken in this in this perverse way, where like Jackie Robinson’s behavior is very carefully prescribed, so that he doesn’t run afoul of the racism, which is still being indulged by the notion that you are only allowed to have a certain kind of Black player.

And then the entertainment industry is used as another avenue of that; there’s a reference [in the song] to Sammy Davis Jr., how he had this signature move where he would, like, finish a song with a flourish by spinning across the stage on his knees. And just imagining how calloused and shiny his knees must have been by the time he’d reached adulthood, having slid across countless stages on his knees like that. And what was the net benefit of that? The net benefit of that was that he was “allowed” to hang around with white celebrities. I guess the notion that he was treated as an equal is what I’m calling into question there, in that they created a caricature of him — or he was forced to create a caricature of himself — in order to be considered one of them. What he didn’t do, what he wasn’t allowed to do, is he wasn’t allowed to have all of Black culture embraced as equal. What he was allowed to do was sneak in in this kind of way that marginalized him and diminished him.

And Satchel is a good example of that kind of caricaturization, too. When he finally does make the majors…

It’s as an old man.

Right, and as sort of a novelty — with a rocking chair for him in the bullpen, and all that.

Yeah.

You mentioned rotisserie baseball earlier. Are you a fantasy baseball player?

I am not. I don't have the time or the attention span to pay attention to teams that don’t interest me. [laughs]

Yeah, I’ve never been into it either. I don’t want to root for some player to have a good game against my Tigers just so it’ll help my fantasy team.

When I first heard the term “fantasy sports,” I instantly thought of, like, wizard tennis, or orc jousting. That’s what I thought when somebody said “fantasy sports”. And I still want that to be true. [laughs]

I would totally play fantasy sports if that’s what they were.

There’s certain certain class of baseball [fan] that fills out the scoresheet, like the guys that have a scorecard for every game they’ve attended. I am not that kind of a fan. I admire it, and I think that is a fantastic way to document your life in baseball is to have a handwritten account of every game that you’ve watched; I think that's incredible. But I could never do it.

Did you ever play any like games like Strat-O-Matic or APBA?

No, but I do remember when Strat-O-Matic came out. I thought it was charming and interesting. I would always look at box scores, but I would only scan the box scores; I I wasn’t a “deep dive” kind of guy.

You talked about following the Reds as a kid and the Twins in the nineties. Do you have a team now?

Not really. When the Expos moved to Washington and became the Nationals… I had a kind of an affection for the Expos and the the my interest in baseball was starting to rekindle in the nineties. And if you think about the incredible talent that came through the Expos… like if the Expos had been able to hang on to half of the players that came through there — you know, Pedro Martinez, Randy Johnson, fucking Vlad Guerrero — they could have been a team as dominant and powerful as all of the teams that they sold their players to. And so there was something kind of tragic about the strike season and the Expos; when the strike hit, the Expos were in first place, and it looked like maybe they weren’t going to be in constant fire-sale mode, you know. And then the strike happened, and it scuttled all the energy, and the local fanbase just collapsed.

And so when the Expos moved to Washington, DC, I felt a kind of an envy for baseball fans in Washington, because I had the feeling that they were going to be able to see a great team built, or a team that had the potential to be a great team built. And it seemed like that would have been a good time to become a Nationals fan. And, you know, [they had] some terrific young studs and a lot of promise. But I think it would have been very frustrating had I committed to being a Nationals fan at that point. [laughs]

So yeah, I don’t have a particular team right now. I’m always fond of, I’m always rooting for the White Sox; because it feels like within the city, the White Sox are culturally less important. They feel like underdogs inside the city. So I'm rooting for the White Sox.

Here’s a conceptual question: If you could pick one player from baseball history to be in a band with, who would it be? They don’t necessarily have to have any music talent, but something about their personality, their vibe, their energy would make you go, “Yeah, this guy!”

Yeah, I’m reluctant to cross disciplines here, because I have heard some music made by professional athletes and their side project bands, and I cannot endorse it. I cannot endorse the pastime and I cannot endorse that kind of interdisciplinary enthusiasm. I prefer to let baseball and music be… as Richard Dawkins said, I believe that they should they should be separate magisteria. They should operate under their own terms for their own ends, and let’s not worry about having them commingle.

I take it you’ve heard Jack McDowell’s music?

Among other people’s, yeah. I think what we have learned from what we have learned from Curt Schilling's adventures in electronic gaming is that being good at baseball, or being good at some aspect of baseball, does not qualify you for anything else in life. Baseball is baseball. Everything else is everything else.

I really thought Steve was going to make a connection between Geddy’s love for rotisserie baseball and rotisserie chicken. Alas, no.

I always hated those lights. I was an ice cream man that summer in the suburbs of Mundelein and Buffalo Grove. I had a yellow "No Lights In Wrigley Field" shirt. And I was so happy that the night they wanted to unveil those things, God Himself, sent down a rainstorm and washed the game out.

Little did I know those things hurt that neighborhood so much. Thank you for this.