Copious amounts of ink have already (and deservedly) been spilled about the life and work of Steve Albini, who died last week of a heart attack at the far-too-young age of 61. I can’t pretend that I was ever a fan of Albini’s music with Big Black, Shellac, etc., his clinical approach to record producing — with the exception of The Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, I can’t think of a single album he recorded for any artist that I genuinely prefer to their other work — or his more obnoxiously “edgy” fanzine contributions from back in the day. Hey, if you dig/dug that stuff, that’s cool; it just wasn’t ever my thing. And since the man himself prized honesty and integrity above all else, I don’t think he’d want me or anyone else blowing smoke up his prematurely departed ass.

Still, there’s absolutely no denying Steve Albini’s massive influence on underground and alternative music (I can’t think of a more important musical figure to come out of Chicago in the last 40 years), or his painstaking devotion to technological excellence in recording. And I have always sincerely admired his commitment to the D.I.Y. ethos, as well as his generosity to lesser-known musicians and his clear-eyed assessments of the music business. Regarding the latter, Albini’s 1993 Baffler piece “The Problem with Music” — which likened dealing with major labels to swimming through a trench filled with decaying shit, and got even less appetizing from there — remains a must-read for anyone who still dreams of “making it big” by playing music, even if the music biz landscape has undergone significant changes over the last thirty years.

Albini was widely known to be a massive baseball fan, and he actually founded a local semi-pro team — the Winnemac Electrons — that still plays to this day. So back in 2017, when some of my Chicago pals and I decided to try and make a documentary film about the intersection of baseball and music (specifically of the punk and metal varieties), Albini was a no-brainer addition our interview “wish list”.

(That documentary, The Baseball Furies, was screened last fall at the Sound Unseen Film + Music Festival in Minneapolis, but it’s still looking for distribution and/or a streaming outlet. While I haven’t been closely involved with the project since leaving Chicago in 2018, I’m still in contact with the folks who are — so if you’re reading this and might be able to help bring The Baseball Furies around to score, please give me a holler and I’ll connect you with them.)

True to his rep for being approachable, unpretentious and generous with his time, Albini actually wound up being the first musical luminary who agreed to do an interview for our cameras. When I sat down with him for the interview in April 2017 (which turned out to be the first and only time we ever met), he cautioned our crew before the cameras started rolling that he probably didn’t have a whole lot to say about baseball; he then proceeded, with very little prodding on my part, to deliver almost an hour’s worth of articulate, insightful and massively entertaining thoughts on the subject.

Our interview has never run anywhere before, but thanks to the generosity and enthusiasm of my buddy Jason Dummeldinger — the main man behind The Baseball Furies — I can now post it here at Jagged Time Lapse. It’s way too long for one post, but you can find Part Two here…

Okay, for the cameras — who are you?

My name is Steven Frank Albini. My number has been retired from the Winnemac Park Electrons baseball team of the Chicago Metropolitan Baseball Association, an independent semi-pro league that has been operating since 1927. We are two-time champions and repeat champions — I say “we” because I have an affiliation with the team, but I haven’t played for eight years now, or something like that. In one year for the Electrons, I went oh-for-the-season at the plate. So that's not why my number was retired. [laughs]

Was your number retired so it wouldn't infect anyone else?

No, my number was retired because I was part of the crew of degenerates, drunks and wannabes who started the Winnemac Park Electrons. It would have been in 2008. There had been a gradually growing interest in pickup baseball games in my circle of friends. And one of my circle of friends found [out about] the Chicago Metropolitan Baseball Association; all it took to form a team was to have enough people pay dues, and then you were in.

So we got together a bunch of people; it was more of a drinking team that played baseball than a baseball team that drank. In our first year, the first season of the Electrons, I made a wager with the roster that if we won two games outright — that is, not by forfeiture — I would take everybody to Medieval Times. We did it, and I put an ad in The Onion with an illustration of our our team celebrating our second victory, and announcing that we had clinched Medieval Times. [laughs] But we never actually made it to Medieval Times.

That’s disappointing.

Yeah, I feel like it’s an obligation that I owe a dozen of the stoutest baseball players in the city.

What position did you play?

I was listed as the catcher, but I never played. I just warmed up as catcher, and I played second base or first base.

Did you play baseball as a kid?

Yeah, I played baseball from the age of about seven until about 13, something like that. My interest in baseball was piqued by the early seventies. In 1970, my family moved to Washington DC, just as the Senators were leaving. Although I did get to see an exhibition game, sort of a “farewell to the fans” exhibition game between the Senators and the Red Sox, and there was a home run derby between Frank Howard and Carl Yastrzemski, I think; it was pretty awesome. That was like the last hurrah for baseball in Washington DC.

At RFK?

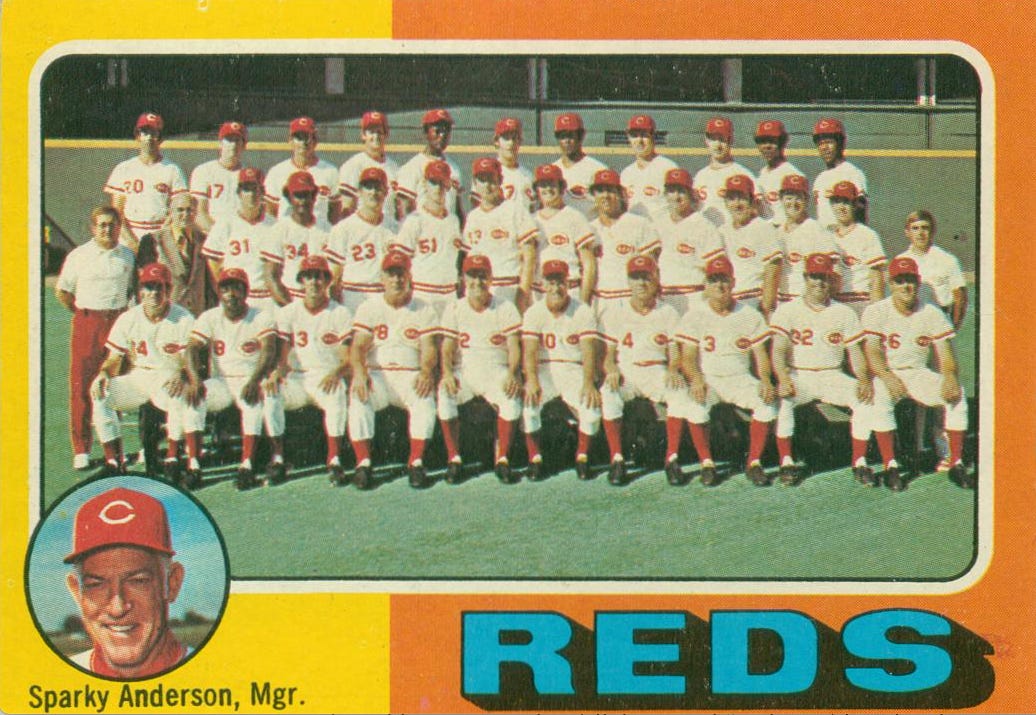

At RFK! Imagine having a home run derby like one of the largest ballparks ever. [laughs] So the team was leaving just as I was coming to town, and everyone sort of treated the Orioles as a local team after the Senators left, and so there was a lot of enthusiasm because they [the Orioles] were in the World Series that year. And that’s where I found my abiding baseball passion, which was the Cincinnati Reds — the Big Red Machine. That was the team of my youth and adolescence, the team that I idolized.

So you discovered them when they played the Orioles in the 1970 World Series?

Yeah, I was a kid and I saw them in that World Series, and it was tremendously exciting to see those guys play. I mean, Joe Morgan wasn’t [with the team until] a year or two after that, but what an incredible lineup. Every day you’re gonna have essentially four Hall of Famers playing — Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Joe Morgan — like, what a great lineup to watch. Just as my interest in baseball was waxing, getting to see those guys play on television… and I was a catcher, and Johnny Bench revolutionized catching. But it was just such a terrific team to watch.

This was an era where players were growing their hair long and wearing mustaches, but the Reds were super clean-cut. Did that have anything to do with your Reds fandom?

Yeah, the Reds were super square. But I don't think I cared about that at all. There is so much external to baseball that people attach to baseball. And if you get hung up on that, like if you get hung up on the fact that, you know, Jake Arrieta was a Trump supporter or something like that, you’re gonna blow your brains out. You have to just divorce every aspect of culture from baseball in order to appreciate baseball. Because think about it: They’re millionaire professional athletes. What kind of people are they going to be? They are going to be the most self-centered, most hedonistic jocks you’ve ever encountered in your life. They’re gonna be the most entitled, stuck-up, headstrong motherfuckers; they’re all Curt Schillings. Like, every one of them, from a AAA scrub to a Hall of Famer, they’re all just quite likely to be reprehensible people. You can’t attach yourself to that.

I’ve had similar conversations with people about team owners. They’re like, “Oh, George Steinbrenner was such a horrible person.” And it’s like, well, with the exception of Bill Veeck, most MLB owners have historically been pretty horrible people in one way or another.

And, you know, and there’s been some interesting stuff written about it. Like, Jim Bouton wrote a book [Foul Ball: My Life and Hard Times Trying to Save an Old Ballpark] about stadium funding and the operation of a minor league franchise — and that extrapolates into the major leagues, because the thinking behind public funding of stadiums is exactly the same. And, I mean, it’s comical what baseball gets away with politically. There’s no other grotesquely profitable enterprise that’s shielded from labor relations laws that has, you know, essentially monopolistic control of an industry that also gets public funding for its operations. [laughs] I mean, it’s absurd. So you have to divorce yourself from any notions of propriety for the business or the culture of baseball.

And the punditry around baseball is just astonishingly stupid. You have people like Joe Morgan, people from the pre-steroids era, crowing about the purity of the game [back when they played it], when Sandy Koufax was being injected with steroids before every start, and there were literally bowls of amphetamines available in the clubhouse. The punditry around baseball, the socialization of baseball players, the abject racism of the baseball fans who ascribe to ethnicity certain skill sets and stuff like that, it’s all awful. All of it is awful. The only way to enjoy it is to watch the game.

So, all that said… why do you love baseball?

It’s a perfect game. [laughs] It’s like no other team sport. If you put aside contests like feats of strength or running of races, that sort of thing, there’s basically only three kinds of sport. There are “pong” sports, where a ball goes back and forth, and you score by defeating the return of a ball. All “pong” sports are the same, like volleyball, tennis, badminton, ping pong, squash. There are “mob” sports, where you have two mobs fighting over a ball, and whoever gets the ball tries to move it into a goal — and when the bell rings, whoever has the most points wins.

So that’s hockey, football…

Hockey, football, soccer, basketball, lacrosse… they're all the same, right? All those sports are the same. They have a fucking clock. How stupid is that? [laughs] How stupid is it to have a clock, right? So there are “pong” sports and “mob” sports and baseball. Baseball, the unique game, where the ball doesn’t do the scoring — actual people have to do the scoring. The unique game where the defensive team is in control of the ball, right? What a brilliant design. Athleticism helps, don't get me wrong, but the best baseball teams are not always the most fit teams; the best baseball teams are the teams that execute specific plays, and that have general aptitude and knowledge that allows them to adapt on the fly. It’s much closer to chess than it is to a more purely athletic sport, like basketball.

And it’s a game where players can still play even after certain physical skills deteriorate, like good hitters who can’t run anymore.

Sure, they can still play, they can still be an asset. Or you can utilize their knowledge of the game in a coordinating position, where they’re not expected to execute certain things. And the other thing about baseball that makes it amazing, is that an individual game very often doesn’t matter. Sometimes, you know, an individual at-bat is fucking critical, which is incredible. But the whole thing about baseball is that it is very small edges and adjustments, where the experiments are run in many, many iterations. So over the course of 162 games, you discern the thrust of a particular team’s ability. Some teams are managed so aggressively over the course of a season that you don’t really have a picture of how the team performs; but you have a very clear picture of how the manager uses his assets.

The the other beautiful thing about baseball is that it is literally limitless… there isn’t some external arbiter that tells you the game is done; somebody has to win. I think that’s an amazing aspect of the game. I also love all of the small nooks and crannies of the game that are not so much like oddities of the rules as oddities of the structure of the game, where certain things have to happen before something is decided. Like here’s a nice trivia question: If a batter stands frozen in the box, and he never moves the bat, and a ball never hits him or the bat, what is the largest number of pitches he can see before he is awarded a base or is out?

Six?

No. Let's say he stands there and the count is run full — so that’s five pitches — and then the base runner on first is picked off. The inning is over. The next inning, the at-bat continues. The count is run full, he sees five pitches, and he is awarded a base [on the sixth pitch], except that there is an outburst, and the game is awarded to the other team by the umpires as a forfeit. The forfeit is contested, and it is ruled that it was an incorrect forfeit, so the inning has to be replayed starting at the beginning. So then the count is run full again. So that's a total of 15 pitches; unique circumstances, but totally within the bounds of the game. So after the 15th pitch something or other would have to happen, but there could be another outburst. But let’s assume that, you know, you can only have one freakish event per at bat. [laughs]

Are you into to baseball statistics?

To a degree. I have a hard time grasping some of the more esoteric stats, just because the adjustments are made using constants that aren’t obvious, like when stats are adjusted for park effects, and things like that. I am impressed at the kind of quiet revolution that Bill James and people like him started in baseball, and I think it does make for more informed conversations about what’s happening in baseball and who’s good at what.

I think it’s also changed the way that teams are built.

Oh, absolutely.

I think that's really the first time we've seen like, you know, non-players and non-executives actually having an impact on the game.

Well, other than in the political sphere. I also I really admire the notion that the records of baseball are not purely historical; they’re actually dynamic. Like, you can go back through history and discover things about players that you didn’t know. So, for example, everyone thought Lou Gehrig was a tremendous hitter, a tremendous ballplayer, right? But it was only in light of modern analytics that you could see that in the lineup that he was in, in the parks that he played in, against the pitching that he faced, he was actually an incredible hitter. Like, instead of being one of the Top 20 hitters ever, he’s in the Top Five or something like that. So that sort of thing I think is great. And I also love the fact that you can not just retroactively find gradations of greatness or whatever, but you can validate your pet enthusiasms as a fan — like, guys that you that you thought were charming or interesting ballplayers.

I had a conversation with Nate Silver, this statistician who has become famous in the political arena but started his life as a baseball stats geek. And he developed a system called PECOTA, which predicted performance over a season. And it was named after Bill Pecota, who was a journeyman ballplayer who apparently had like an .800 or .900 OPS specifically against the Tigers. [Note: Bill Pecota had a .836 lifetime OPS against the Indians.] He was just a utility player, but Nate Silver really liked him for some reason, and made a backronym for his statistical thing just to enshrine his enthusiasm for Bill Pecota.

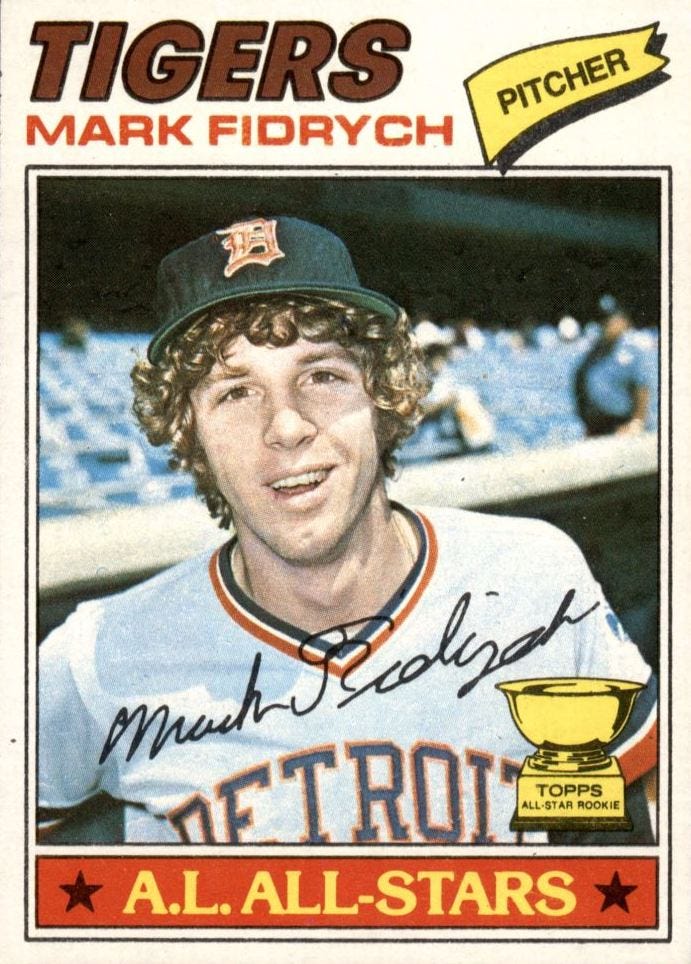

Another great example of that is Mark Fidrych, one of my all-time favorite players. He was the American League Rookie of the Year in 1976, his one great season; but if you go back now and look at the advanced statistics, he should have been given serious consideration for both the AL Cy Young and MVP awards, as well. He was that much beyond everybody.

He was also one of the most one of the most charming people to watch play baseball. Just his genuine, boundless enthusiasm for the game — like, that mirrors what every kid who played baseball was into.

Absolutely. So, going back to the political side of the game, and the capitalist side of the game…

Indefensible. All of it 100% indefensible.

I was really into baseball as a kid — but then between learning about all that stuff, dealing with jocks and discovering punk rock, baseball became less appealing and music became more appealing. And at some point, I thought, “I can’t be into sports and be into music.” Did you have a similar experience?

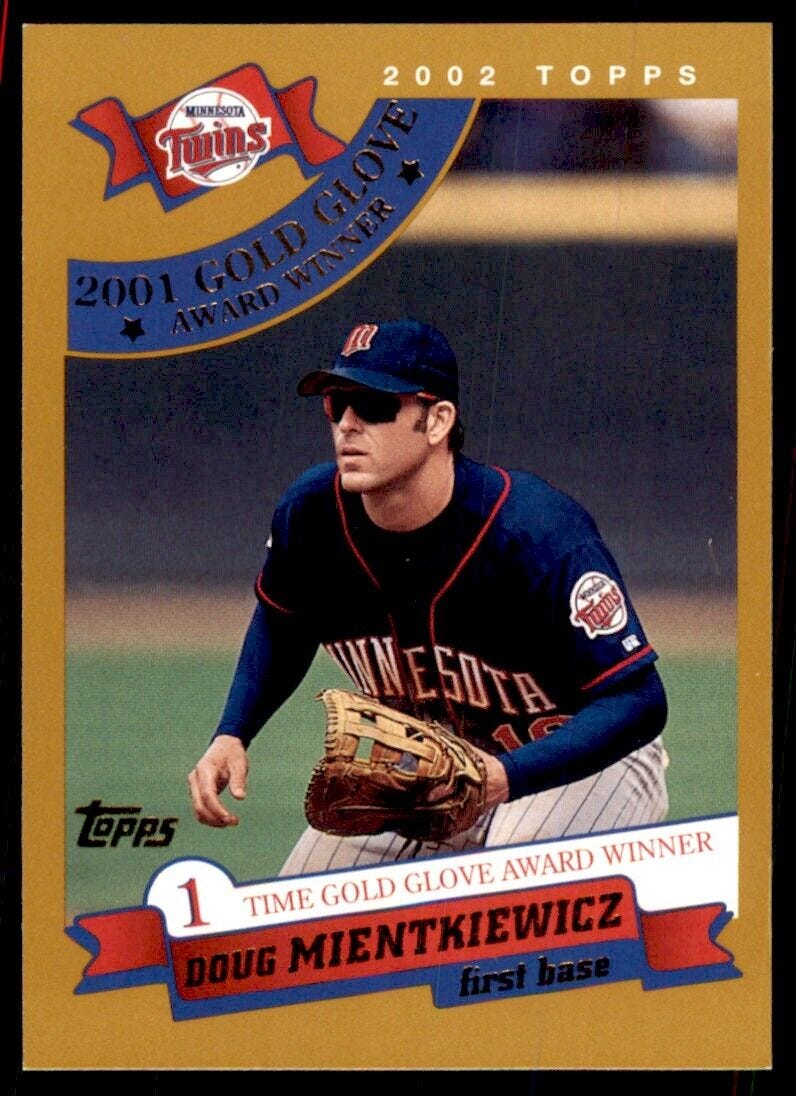

I definitely took a hiatus in my enthusiasm for baseball when I discovered punk rock. Like, I was oblivious to baseball from probably 1978 until the early nineties. Music became an abiding passion, and I threw myself into it. I had a kind of a tunnel vision about it, in the way that somebody is born again, and, you know, casts off the childish things. I was perfectly comfortable writing off baseball as an unenlightened part of my life, you know? And then, in the nineties, I developed an enthusiasm for one particular team, the Minnesota Twins, and I followed the Twins to a degree during during the late nineties.

What brought you back?

I don’t know… As stupid as it sounds, I think it was that there was a kind of a unity of the infield there where you had, um, what's his name?

Chuck Knoblauch?

No, I actually sort of started paying attention after the Knoblauch trade. Although, Chuck Knoblauch — classic baseball name. Like, you know, Top 20 baseball name. [laughs] Hang on, give me a minute… Doug Mientkiewicz! The gymnastic first baseman with the high pockets. When I saw that guy, stealing outs left and right, it made me think, “Maybe first base is an honorable position.” [laughs]

Every week, I got into a big debate with a friend of mine on an internet forum talking about the the Twins. And I was like, “Okay, who is more valuable? A guy that hits one home run a week and strikes out the rest of the time? Or a guy that that gets you an extra out a game?” And it’s probably pretty close, but I think the extra out is probably worth more. And so there was a big discussion about whether or not Doug Mientkiewicz [getting] an extra out a game compensated for the fact that he was a modest hitter. And I mean, it really was incredible seeing him; he played first base as though he was a third baseman — the Brooks Robinson of first base, or whatever. [laughs] And then AJ Pierzynski is an incredible baseball mind. He’s like an unrepentant asshole, and clearly one of the worst people, right? But if he’s on your team, he’s your asshole. Like, you own him, and you are so down with him using every dirty trick and shooting every angle, like, you know, stepping on the middle of somebody’s back. You’re fine with all of it, you know? [laughs] Was it Aaron Boone, where he stepped on the middle of his back?

Yeah, I think so.

That was just like the purest “fuck you”. [laughs] A guy is sprawled out, giving his all trying to make a play, and you just step on him. Like, so so horrible. And this is a guy who, when he was playing for the Giants, he grounded into more double plays than any player in baseball for a season, right? So it’s not like he’s wearing a halo; it’s not like he was an extraordinary asset to his team. He was such a prick, but such an engaging prick to watch if he was on your team.

The other thing I loved about Mientkiewicz — and obviously this goes back to the print days — was the way they used to chop up and abbreviate his name in the box scores. He was king of multiple apostrophes.

[Laughs] Yeah. When the speech-to-text thing first came out for iPhones, my friend Tim Midyett — another baseball enthusiast — and I were sort of testing it and he was one of his favorite ones was “Pierzynski high-fives Mientkiewicz”. [laughs]

Were you a Mientkiewicz-style first baseman for the Electrons?

Oh, no. My right leg was broken in a motorcycle accident when I was a teenager. And when it was reassembled, it was reassembled slightly crooked; I can demonstrate if you like, I don't know if you’re gonna get this on camera. But if I point my feet in the same direction, so that both of my feet are pointed forward, this knee goes forward, and this knee goes in. So if I have my knees going in the same direction, both my knees go forward, but my right foot sticks out at about 15 degrees. So my describing me as a “lumbering baserunner” would be generous. And at the time the Electrons formed, I hadn't swung a bat or thrown a ball in probably 15 years. So it was optimistic for me to to join the storied ranks of the Chicago Metropolitan Baseball Association. [laughs]

But we had to do it. There were a lot of us that liked baseball and wanted to play baseball, and one of the only ways they’d let us was if we each paid $150 for our own uniforms. So we started the Electrons in 2008. If you go to the website, you can see the collected statistics of the proud men of the Winnemac Electrons, and their photos as well. You probably won’t see a photo of me on there, though; just people who were on the field once in a while. [laughs]

Click here for Part Two of this interview, in which we discuss favorite baseball characters, how night baseball at Wrigley Field impacted the Chicago punk scene, and why baseball made Albini revise his opinions of the band Rush.

What a great read! It brought back a lot of memories (my high school baseball team played summer league at Winnemac Park), and playing fast pitching at Hibbard grammar school for years.

Also, running into Pete Rose in Las Vegas, and having a very memorable conversation with him.

Also, I'm old enough to remember that when I was in high school, the Cubs weren't the phenomenon they are today in terms of attendance. They were drawing 5,000 people a game, so to put asses in the seats, they gave season passes to high school baseball coaches to give to their players. My buddies and I went to dozens of games with those passes.

Great read! I also am not a huge fan of a lot of his musical output but I do think Man Or Astroman's work sounded its best with Albini. It is kind of the one band that I really think that.