Favorite L.A. Albums, Part Three: Goodbye Yellow Brick Road

Flashing back on Elton John's Hollywood-inspired masterpiece

Two weeks ago, wracked with feelings of sorrow and helplessness after watching from 3,000 miles away as the Palisades and Eaton fires spiraled out of control, I decided to salute my former hometown of Los Angeles with a series of posts on some of the records that truly qualify as “L.A. albums” for me — not just because of their provenance or personnel, but because there’s something about them that instantly pulls me back to my own L.A. experiences. As difficult a city as it can be to love at times, I do truly love Los Angeles, and am profoundly grateful for the role it has played in my life… and in my record collection.

These essays are by no means intended as entires in a “Best L.A. Albums of All Time” countdown, but rather love letters to L.A. albums that mean a lot to me personally, written to help me process the grief and horror I’ve been feeling over L.A.’s losses during the last couple of weeks, and the anger I’ve felt over the way they are being exploited for political gain. Soulless GOP hacks talk about withholding aid from the region unless California gratefully licks the incoming President’s boots and knuckles under to his every demand, said incoming President blatantly lies during his inaugural address that “we are watching fires still tragically burn from weeks ago without even a token of defense,” and numerous self-appointed know-it-alls on social media spread further falsehoods and disinformation about the causes of the fires and the methods being used to fight them, all while willfully ignoring the fact that climate change is the main driver of this disaster, just as it was with the hurricane and flooding last fall in the mountains of North Carolina. None of us are immune from the dangers of climate change, and you’re not going to be able to legislate, pray, fascist salute or MAGA your way out of 80-100 mph winds, but sure — go ahead and point from the sidelines, braying to anyone within earshot about how L.A. had it coming. And then kindly go fuck yourself.

I’m not sure how many of these L.A. album essays I’ll be writing — I have a running list of candidates, but would rather wait for inspiration to strike than to officially commit myself to penning 5, 10, 20 or whatever. But inspiration is definitely striking at the moment, because I’ve really been missing L.A. these past few weeks. These fires remind me that the mark the city has made on my life — both as a child and an adult — is largely a positive one, and that I would be a much different and far less interesting person today without its influence. And though I moved away from L.A. a decade ago, there are many aspects of the place that I still remember fondly, some of which I hope to reconnect with in person very soon; we’re slowly making progress on an L.A. book event date for Now You’re One Of Us: The Incredible Story of Redd Kross, the details of which will hopefully be ironed out this week. Stay tuned!

The summer of ‘74 was when my fascination with Hollywood really kicked in.

My sister and I spent most of that summer in L.A. with our mom before heading to England with our dad in the fall. At the time, she was living a considerably less than glamorous existence with a couple of hippie friends in a dilapidated Hancock Park craftsman, and yet I imagined that I could feel Hollywood magic and history glowing all around us.

We watched countless movies on TV that summer, everything from downer sci-fi flicks like Silent Running to the early silent comedies that the local stations would play late at night. We caught matinee screenings of new films like The Three Musketeers over at the Wiltern Theater, a magnificent (if also magnificently rundown) Art Deco movie palace wedged into the lower floors of an emerald green 1930s high rise just a few blocks away from the house where my mom lived. We were also just a quick bus ride away from my aunt and uncle’s place in the Fairfax district, where you could see the Hollywood sign in the hills from their bedroom window and I was allowed to rifle through my uncle’s many coffee table books on film history to my heart’s content. To me, movies were the coolest and most exciting things imaginable, and the fact that I was now living (at least for a time) in the movie capital of the world absolutely blew my mind.

We visited Hollywood Boulevard several times that summer, occasionally to catch movies at the wonderfully opulent Mann’s (formerly Grauman’s) Chinese, but mostly just to engage in some budget-friendly pastimes like browsing the grimy boulevard’s many movie memorabilia shops and seeing how many recognizable names we could spot on the Walk of Fame. But after noticing the sign for the Hollywood Wax Museum, I launched a full-scale pressure campaign for my mom to take us there.

Our trip to Disneyland earlier that summer had been kind of a mixed bag — I loved the rides, but felt acute anger and embarrassment when Disney cops actually followed us into the parking lot at lunchtime to search my mom’s friends’ car for “dope,” apparently figuring that these dirty hippies must be stepping out of the park for a reefer break. In the end, all they turned up were the brown-bagged peanut butter and jelly sandwiches we’d brought with us because we couldn’t afford to eat Disney’s overpriced food. (I wouldn’t return to “The Happiest Place on Earth” for another five years, and only then in the company of mormons.)

The Wax Museum, on the other hand, presented no such hassles. From the moment we entered its dark, air-conditioned confines, I was completely and blissfully cut off from the cares and unpleasantness of the outside world. The attraction was even better than I’d hoped: I’d expected to see figures of such Hollywood legends as Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne and W.C. Fields, of course, but I hadn’t figured on running into the Wolf Man and the Frankenstein Monster; nor had I expected to see The Last Supper, The Beatles and various U.S. presidents and world leaders rendered in wax. The whole place seemed so weird and wonderful to my eight year-old eyes, and I glided through its halls in a state of rapt enchantment.

Towards the end of our visit, we came across a figure I didn’t recognize: He wore star-shaped sunglasses and a manic grin, and appeared to be doing a handstand on the piano. “Who is that?” I asked my mom. “Oh, that’s Elton John,” she said, in the same no-nonsense tones she’d used to explain Elvis to me a few years earlier. As with Elvis, I was immediately too distracted by the unusualness of Elton’s name to ask any further questions; “Elton” sounded less like a name to me than an adjective or a verb, and I figured it must relate to his hand-standing action — like his name was John and he was known for Eltoning, or something like that.

Of course, Elton John was already a major rock star by the summer of ‘74 — hence his wax figure — and my complete unfamiliarity with him was due entirely to my complete cluelessness when it came to pop music. At this point in my life, I only ever listened to the radio when we were in the car, and I knew the words to more TV theme songs than I did to current pop hits. I could easily identify the songs of such parental favorites as Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, Carole King, Kris Kristofferson or The Eagles, but I couldn’t have told you a single thing about them or their place in history, whereas I could have easily rattled off the names of every classic 1930s horror actor and the highlights of their respective filmographies. Pop music was simply an alien world to me, and not one that I felt any particular pull to explore.

That would change, of course, beginning in the summer of 1976; even though my interest in baseball was already outpacing my interest in movies, my ears were definitely perking up at the sound of AM hits like Wild Cherry’s “Play That Funky Music,” The Bee Gees’ “You Should Be Dancing,” Johnny Taylor’s “Disco Lady,” Wings’ “Silly Love Songs” and “Let ‘Em In,” and Walter Murphy and the Big Apple Band’s “A Fifth of Beethoven,” all of which would stay in my head for hours or even days after hearing them on the radio. “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” Elton John’s chart-topping summer duet with Kiki Dee, was the first new Elton single I can recall hearing (or at least being aware of) in real time.

By 1976, my mom was sharing the lower level of a Spanish-style duplex in Carthay Circle with her friend Julie, who was by far the most knowledgeable film buff I’d met in my life, especially regarding the movies, stars and costumes of the 1920s-50s. Julie was always game for going to the movies, especially if it was something with a big costume budget, and during the summers of ‘76 and ‘77 I got her to take me to several films that my mom had no interest in seeing, like Swashbuckler (a now justifiably forgotten pirate film starring Robert Shaw) and Star Wars.

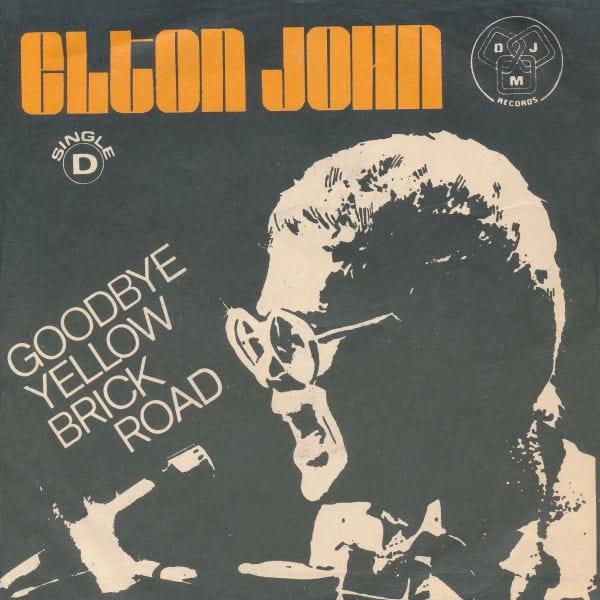

Julie also had records, lots of ‘em. In time, she would bequeath me most of them, but for now they were still mystifying artifacts to a ten year-old who had no concept of how to work a turntable. Elton John was one of the few artists in her collection whose name I recognized, so one day I pulled out a few of his albums to have a look… and came face to face for the first time with Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.

I could say that I put the album on right there and immediately fell in love with the music, but that’s not how it played out — in fact, it would be well over a decade before I actually heard the entire album. But I did immediately fall in love the colorfully evocative artwork of the album’s packaging; between Ian Beck’s cover image of Elton stepping with ruby stack heels into a life-size poster of the Yellow Brick Road from The Wizard of Oz, the interior illustrations of David Larkham and Michael Ross, and the old-timey postcard-style photos of Elton, his bandmates and his lyricist Bernie Taupin, I immediately understood that this album was Elton’s tribute to classic Hollywood.

And if I couldn’t relate to the music yet (my earliest memory of hearing “Bennie and the Jets” on the radio is of being deeply annoyed by the overdubbed applause), I could at least relate to Elton as a fellow fan of the movies, and of classic Hollywood iconography. He was a rock star from England and I was a fourth-grade graduate from Ann Arbor, Michigan, but we were coming from pretty much the same place in our nostalgic fascination with the glitz and glamour of the Hollywood dream machine.

Truth be told, I didn’t really become an Elton John fan until the early nineties, when Polydor gave his Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and the rest of his seventies MCA/DJM catalog the remastered CD treatment. My girlfriend at the time had been a major Elton fan since childhood, so I started bringing these new reissues home for her from the record store I worked at. Listening to them with her, I was immediately knocked out by the prolific pop brilliance of the Elton-Bernie songwriting partnership, and by the note-perfect way guitarist Davey Johnstone, bassist Dee Murray and drummer Nigel Olsson helped to bring their songs to life.

I dug most of these albums — especially 1970’s rootsy Tumbleweed Connection — but Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was the one I found myself continually going back to. Not only was the album’s batting average incredibly high (“Jamaica Jerk-Off” is probably the only one of the album’s 17 tracks that I could easily live without), but wonderfully melodic songs like the title track, “I’ve Seen That Movie Too,” “The Ballad of Danny Bailey (1909-34),” “Roy Rogers” and of course the Marilyn Monroe tribute “Candle in the Wind” all took me directly back to my early infatuation with Hollywood. Even when the songs weren’t explicitly about films or movie stars, there was something incredibly cinematic about the images that Bernie Taupin conjured up for “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding,” “Grey Seal” (a 1970 B-side rerecorded for the album), “All The Girls Love Alice” and “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting,” and the way that the musicians (and producer Gus Dudgeon) rendered them. When I learned much, much later that one of the album’s working titles had been Silent Movies, Talking Pictures, it made perfect sense. Goodbye Yellow Brick Road may have been primarily recorded in France by British people, and yet it’ll always be an L.A. album for me.

In the summer of 1993, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was in regular rotation as my then-girlfriend were packing up for our move to Los Angeles, its songs psyching me up for a return to the place I’d fallen in love with as a child. Of course, Hollywood had changed by then, and so had Elton — when we paid a visit to the Hollywood Wax Museum a few weeks after our arrival, we found his effigy no longer hand-standing on a piano in his glam finery, but rather regally seated and sporting the straw boater and white linen suit of his mid-eighties incarnation. The star-shaped sunglasses of the seventies remained, however; apparently they were dug in too deeply to be removed without seriously damaging his waxen head. And as jarringly discordant as they looked with that straw boater, those star specs still made me smile, because seeing that pair perched on his nose was like having an old friend welcome me back to Hollywood.

Once again, I’m going to leave you with a list of donation links to organizations that are doing great work on the ground right now, and which could definitely use your assistance if you can give it.

Greater Good Charities Disaster Relief

Los Angeles Fire Department Wildfire Emergency Fund

Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

Pasadena Humane Society and SPCA Wildfire Relief

And if you’re out in Southern California and can lend a hand in person, here’s an extensive list of volunteer opportunities.

And as per Rock 'n' Roll with Me, if you’d like to assist any of the musicians or Black and Latino families that have been displaced by the fires, there areplenty of GoFundMe’s to contribute to — including one for my friend and fellow Substack writer S.W. Lauden, a.k.a Steve Coulter, whose family lost almost everythingin the Eaton fire.

Finally, I’d like to thank everyone in L.A. and elsewhere who has pitched in to help the people and animals whose lives have been massively impacted by this tragedy. Despite all the ghouls and jackasses, there are a lot of good folks out there who realize that the only way through crises like these — and all the other shit that will likely blow our way in the foreseeable future — is via togetherness, combined action and mutual assistance. Even from 3,000 miles away, I feel honored and energized to still be a part of the L.A. community.

I rarely think about such things but I think Elton would be a wonderful name for a cat.

I didn't know that history of that album. Really enjoyed hearing your experiences as a youngster in L.A. discovering Elton in the wax museum.

His and Bernie's music was the soundtrack for my first year at college. How lucky were we?