Greetings, Jagged Time Lapsers!

How are y’all holding up? This past week has felt like a particularly dreary and infuriating month, so I took a little time out to recharge my batteries with a quick visit to NYC, and by immersing myself in some soul-salving music…

It seems like a year ago now, but it was just a few weeks back that I paid a visit to Rocket Number Nine, my favorite record store in this general alley of the Hudson Valley, and traded in a bunch of LPs that were taking up unnecessary space in my collection (redundant doubles, once-played impulse buys, lousy-sounding reissues that I’ll likely never listen to again, etc.) for some things that I really wanted to own.

As often occurs in these sorts of transactions, I wound up with a little bit of leftover trade-in credit, so I quickly scanned the five-dollar jazz bin to see if anything interesting was lurking within. Much as I love Miles, Monk, Coltrane, etc., I also have a real taste for sixties and seventies jazz stuff that spills into the realms of easy listening, library music or light fusion, and is thus (with the exception of highly-sampled examples like Pete Jolly’s lovely Herb Alpert-produced Seasons, which I happened to pick up on this particular Rocket mission) less interesting to collectors as well as more affordable. Which is why any five-dollar jazz bin is always worth a look for me, whatever record store I happen to be in.

George Benson’s albums often wind up in the budget bins, both because so many copies were sold of hits like Breezin’ back in the seventies that they remain really easy to find today, and because — at least for many “serious” jazz aficionados — his massive pop success cast a suspicious pall over his jazzier early work. I don’t roll particularly deep with Benson or his discography, but I enjoy a lot of his instrumental work. His playing came from the same soulful school as Wes Montgomery and Grant Green (my two favorite jazz guitarists), which is reason enough for me to occasionally pick his pre-eighties albums up if they’re in good shape and affordably priced.

I’d never even heard of Benson’s Shape of Things to Come LP until a few weeks ago, when I saw it sitting in Rocket’s five-buck jazz bin. I didn’t scan it very closely before adding it to my pile — all I needed to see was the A&M logo, the “arranged by Don Sebesky,” and the cover photo by Pete Turner (whose dramatic work adorns the packaging of A&M/CTI albums by Wes Montgomery, Hubert Laws, Walter Wanderley and many others) and I was sold. But on the way out of the store, I thought to myself, “Shape of Things to Come, huh? He couldn’t possibly be covering that song, could he?”

I first heard “Shape of Things to Come” — one of the many, many indelible pop gems penned by songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil — as recorded under the fictional moniker of Max Frost and the Troopers for the soundtrack of Wild in the Streets, the 1968 AIP youthsploitation flick in which American teens (led by charismatic rock star Max Frost, as played by Christopher Jones) successfully demand that the voting age be lowered to 15, and everyone over 35 winds up being herded into “re-education camps” and given constant doses of LSD. (Not an ideal situation, to be sure, though I’d happily take it over our current fascist, white supremacist shitshow.)

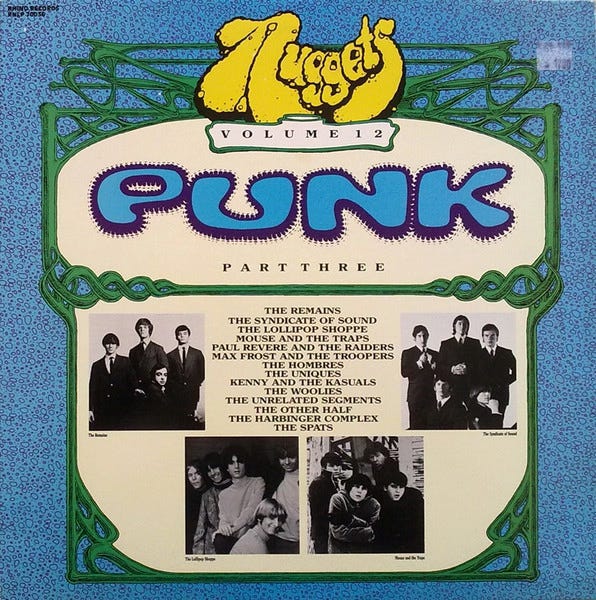

But the first time I heard the song wasn’t in the film’s soundtrack (which I wouldn’t find a copy of until 1988) or the film itself (which I wouldn’t actually see until 1991 or so), but on Nuggets Volume 12: Punk Part Three, the awkwardly-titled Rhino compilation from 1985 that also hipped me to such then-obscure sixties garage rock slammers as Kenny & The Casuals’ “Journey to Tyme,” The Other Half’s “Mr. Pharmacist,” “I Think I’m Down” by The Harbinger Complex, all of which subsequently wound up in heavy rotation on my college radio show “Peace, Love and Fuzztone”.

While a great many of the tracks on the compilation were endearingly raw and sloppy (save for the ones by more “pro” bands like Paul Revere & The Raiders and The Remains), “Shape of Things to Come” stood out with its almost assassin-like precision and efficiency. A taut, tension-filled verse builds steam over a simple but killer chord progression before exploding into a declarative chorus, then does it again; then the song shifts gears for a brief bridge before returning to the verse and chorus, and then heads for the exit. It’s all wrapped up in a hair under two minutes; there isn’t even a guitar solo!

I absolutely loved “Shape” from the first time I heard it, and wasn’t at all surprised to discover that numerous rock and garage bands had covered the song over the years; hell, even Janelle Monae gave it a go. I have a vague memory of my band Lava Sutra jamming on it a bit in rehearsal, though I’m guessing we could never could quite nail the tension-and-release dynamic that made the original recording so compelling. (I still have absolutely no idea which musicians are actually playing on the original, by the way.)

My favorite cover version is probably Slade’s, which was released as a UK single in 1970 but totally flopped. Noddy Holder’s vocal is (as usual) a thing of throat-roaching beauty, and that little morse code warning bit that he and Dave Hill do coming out of the instro break kills me every time.

Still, all the covers I’d ever heard of “Shape” (even Janelle Monae’s) stuck pretty closely to the short, sharp, aggressive blueprint of the original recording. So the idea that George Benson might actually try his hand at a soul-jazz rendition of the song seemed pretty absurd, and I laughed to myself while trying to imagine it. Then, about a week after I brought his Shape of Things to Come album home, I threw it on the turntable and… holy shit!

Really, the whole album is wonderful. Released in 1968, Shape of Things to Come was Benson’s first A&M album; the label had signed him to fill the large shoes left by the recently-deceased Wes Montgomery, and paired him with producer Creed Taylor and arranger Don Sebesky (both of whom had worked with Montgomery during his all-too-brief A&M tenure) and legendary engineer Rudy Van Gelder. Five of the album’s seven songs are covers — “Last Train to Clarksville” and “Chattanooga Choo Choo” among them, both of which come out far better than you might expect — clearly chosen to demonstrate Benson’s impressive range as a guitarist. And with such jazz luminaries as Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Richard Davis and Hank Jones chipping in, the record can’t help but be a blast.

But the arrangement and execution of the title cut was what really floored me on first listen. Opening with a slinky organ-and-conga groove (courtesy of Charlie Covington and Johnny Pacheco, respectively), the track quickly hops the first train to Weirdsville, with Sebesky and Benson employing tape-speed manipulation and a Varitone (an electronic pickup which was originally developed to add suboctaves and other effects to woodwind instruments) to create an otherworldly array of tones and effects. Taylor then proceeds to lightly drape the tripped-out jam in flutes and strings, and even though the track stretches out to five minutes and fifteen seconds — over two and a half times the length of the Max Frost and the Troopers original — I’m never quite ready for it to end when it does.

Was this really the “shape of things to come”? Well, not really — and certainly not for George Benson, who to the best of my knowledge never screwed around with the Varitone or multi-speed overdubs again. But if the future had actually turned out to sound something like this, I sure wouldn’t have minded.

Never heard the original before but I loved it! And the Slade and George Benson versions as well!!

Shape of things that were and still

are. This column and your visit to NYC brought to mind a book title from a half-century ago—“What do people do all day?” What was Dan thinking then? What is he thinking now? The benefit of being a subscriber!